Бесплатный фрагмент - Учебник английского языка

Цикл: учебники по иностранным языкам

УДК 811.111 (075.4) ББК 81.2Англ-9 Е 1

Preface:

Автор уникальных технологий изучения языков Денис Иванович Ершов предлагает новое пособие, которое поможет в кратчайшие сроки научиться говорить на английском языке. Достоинство пособия — оптимальное сочетание грамматических сведений и лексического материала. Для работы с книгой необходимы базовые знания английского языка и уровень владения им выше среднего. Книга создана для студентов языковых и неязыковых вузов, а также для учителей и преподавателей иностранных языков. Учебник предназначен для тех, кто мотивирован изучить английским языком и использовать его как реальное средство общения и межкультурной коммуникации. В пособии задействованы достижения когнитивной лингвистики для лучшего понимания и усвоения английского языка.

(Урок №1/Lesson 1)

The author of the textbook: Let me introduce the main instructors of our course. They will be teaching you English day in and day out, from lesson to lesson, throughout this book.

The first teacher we will be introducing is a dog named Charles. Throughout the course, Charles will teach you the pronunciation of English sounds, letters and phonemes.

The second teacher we would like to introduce is a cat named Jasper. Jasper will teach you English grammar.

The third colleague we are thinking of getting to know is a parrot named Fluffy. Fluffy will teach you how to read English texts, as well as the basics of stylistics and other aspects related to this language.

The fourth friend we hope to get acquainted with is a rabbit named Azure. It will introduce you to the basics of English vocabulary and help enrich your vocabulary. You will learn how to make it active and start using it in communication and intercultural interaction. Azure will introduce you to the world of English lexicology and all the elements that make it up, helping you to expand your vocabulary. It will also help you to move words from the passive to the active category, allowing you to participate in communication and intercultural exchange.

Charles: — Hi there, my name’s Charles. Today, I’d like to talk about the phonetic structure of the English language. Can you tell me what you think it is, and how it differs from the phonetic structure of your native language, Russian?

Jasper: — Hi Charles, My name is Jasper and these are my friends Fluffy and Azure. We are all interested in learning about different aspects of the language and although we are not experts in phonetics, we would like to learn more about this area. Could you please help us? Thank you for your time. Best regards, Jasper, Fluffy, and Azure.

Charles: Great! I’ll be happy to explain this and answer any other questions you may have about phonetics and phonology. The phonetic structure of English is quite unique, and learning it presents significant challenges for speakers of Russian, both in terms of sounds and intonation. Mastering the pronunciation of a foreign language requires learning how to accurately produce the sounds of that language, both individually and in connected speech, as well as correctly using intonation in sentences. The phoneme system forms the basis of the sound system in any language. A phoneme is the smallest unit of sound in a language, and it can be described as a sound or group of sounds that distinguish words and their grammatical forms when contrasted with other sounds in the same context. Each phoneme has its own unique symbol according to the phonetic alphabet. These symbols are usually written inside square brackets: [].

In this lesson, we will be discussing the challenges that scholars face when attempting to describe English sounds from a functional perspective. We will explore what is meant by the quality of a sound and the articulatory characteristics that make up that quality, as well as determining which of these are phonologically significant. There are two main categories of sounds that phoneticians traditionally distinguish in any language: consonants and vowels. This distinction is primarily based on the auditory effect of the sounds. Consonants have a combination of voice and noise, while vowels consist only of voice. From an articulatory perspective, the difference between the two is due to how the speech organs function. In the production of vowels, there is no obstruction, while in the production of consonants, various obstructions are created. Therefore, consonants can be described as having a close articulation. By a complete, partial, or intermittent blockage of the air passage by speech organs, consonants are produced. Consonants have noise as their essential and most defining characteristic. We will now consider each class of sounds separately.

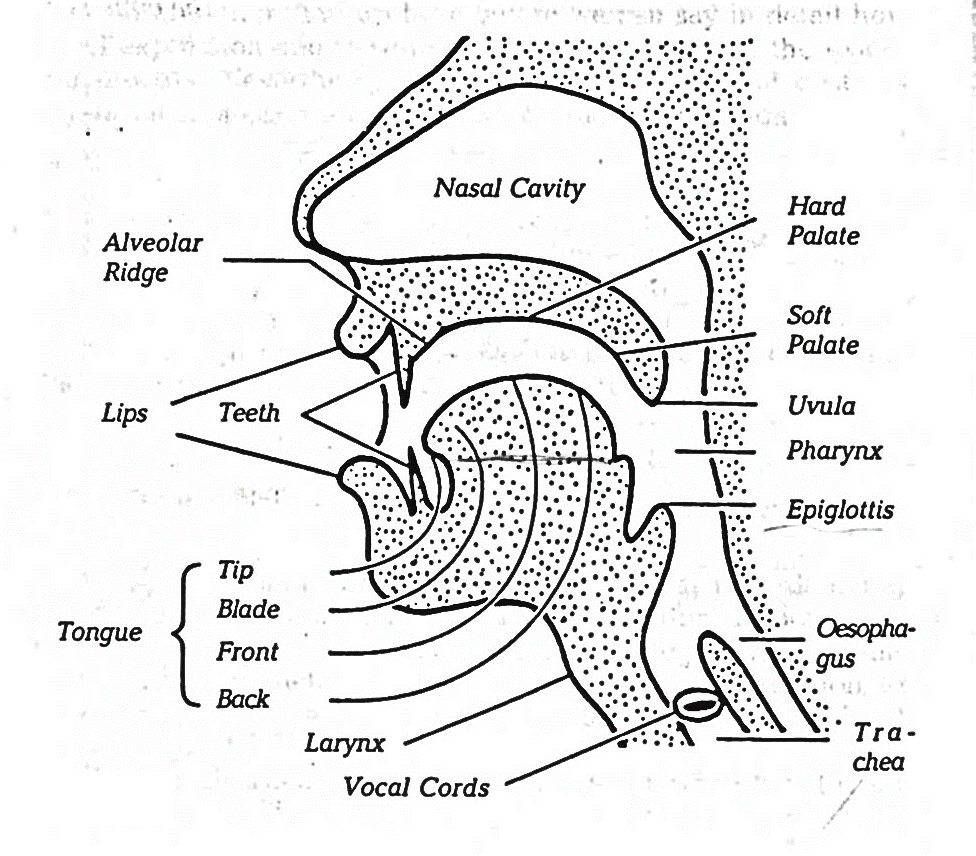

The number of phonemes in a word does not always correspond to the number of letters in it, which can be a challenge when learning English spelling. For example, the word «daughter» contains eight letters but only four phonemes. There are 26 letters in the English alphabet, which represent 44 sounds, including vowels and consonants. This difference between spelling and pronunciation has historical roots. English spelling has remained relatively unchanged over centuries, reflecting the pronunciation of several centuries ago. English pronunciation is taught on the bases of the pronunciation standard of the London accent, which is the foundation of the standard literary pronunciation of Modern English. To master correct English pronunciation, it is essential to familiarize yourself with the structure and function of our speech apparatus. Now, let’s take a look at the organs of speech and how they work. The exhaled air from the lungs travels through the bronchial tubes and enters the trachea (see Fig. 1). The upper part of the trachea is called the larynx. In the larynx, there are two muscular, elastic, and movable folds called vocal cords. The space between the vocal cords is called the glottis. When we pronounce voiceless consonants, the vocal cords do not vibrate and are not tense.

However, when we speak with a tense and closed vocal cord, the air passing through the glottis causes the vocal cords to vibrate. This is how we produce sounds that we perceive as vowels, voiced consonants, or sonorous sounds. Above the larynx, there is a cavity called the pharynx or throat. The following speech organs are located in the oral cavity: the tongue, the palate that separates the oral cavity from the nasal cavity, teeth, and lips. For convenience in describing the production of sounds, the tongue is divided into three parts: the tip, the middle, and the back. The palate consists of the alveoli (small bumps behind the upper teeth), hard palate, and soft palate with a little tongue. At rest, the front part of the tongue is located against the gums and alveoli, the middle part is located against the hard palate, the back is against the soft palate.

When the movable part of the soft palate is raised, the passage for the air jet into the nasal cavity is closed, and when its position is lowered, the air flow passes through the nose. The organs of speech are usually divided into active and passive. The active organs of speech include the vocal cords, the back wall of the pharynx, the soft palate with a small tongue, lips, tongue. They are mobile and in the process of sound formation occupy one or another position in relation to the passive organs of speech: teeth, alveoli, hard palate, which are stationary.

Fig. 1

Azure: What Charles is talking about is both interesting and challenging.

Charles: There is plenty of theoretical material on English phonetics in the first lesson, so let’s move on to practical consolidation. To help you with this, I suggest that you answer the questions I have prepared for you based on the material we covered.

Exercise 1. Answer the questions.

1.Describe the main components of the phonetic system of the English language. 2.Describe the articulation apparatus and how speech sounds are formed. 3.How many sounds and letters are there in English? 4.What sounds exist in English and what is a phoneme? 5.How does a phoneme differ from a sound and a letter?

Jasper: Слова в языке, в зависимости от их формы и значения, группируются в грамматически значимые категории. Эти категории называются «частями речи». Некоторые учёные предлагают более широкое понимание частей речи, рассматривая их как «лексико-грамматические» ряды слов или «лексико-грамматические категории». Они выделяют не только грамматические, но и семантико-лексические свойства слов, что позволяет более полно описать их роль в языке [Смирницкий, (1), 33; (2), 100]. По мнению М. Я. Блоха, что термин «часть речи» имеет условный и традиционный характер [М.Я.Блох, с.38]. Его нельзя воспринимать как что-то определяющее или объясняющее. Этот термин был введён в грамматической науке Древней Греции, где понятие предложения ещё не было чётко определено, в отличие от общей идеи речи.

Поэтому в то время не проводилось строгого разграничения между словом как словарной единицей и словом как функциональным элементом предложения. В современной лингвистике части речи классифицируются на основе трех ключевых критериев: семантического, формального и функционального. Семантический критерий предполагает оценку общего значения, свойственного всем словам, которые входят в состав определенной части речи. Это значение принято называть «категориальным значением части речи». Формальный критерий включает в себя анализ специфических особенностей словоизменения и словообразования для всех лексем, относящихся к одной части речи. Функциональный критерий охватывает синтаксическую роль слов в предложении, которая является отличительной чертой той или иной части речи. Эти три аспекта, определяющие категориальную характеристику слов, условно обозначаются как «значение», «форма» и «функция».

В соответствии с описанными критериями, на верхнем уровне классификации слова делятся на смысловые и функциональные. Это деление отражает более раннее разделение на изменяемые и неизменяемые слова. К именным частям речи в английском языке относятся 6 частей речи: существительные, прилагательные, числительные, местоимения, глаголы и наречия. Существительное характеризуется следующими особенностями: 1. Категориальное значение субстанции («вещественности»). 2. Изменяемые формы числа и падежа, а также специфические суффиксальные формы образования (префиксы в английском языке не указывают на части речи как таковые). 3. Субстантивные функции в предложении: подлежащее, объектное, субъектно-предикативное; предложные связи; возможность модификации прилагательными. Признаки прилагательного: 1) категориальное значение свойства (качественное и относительное); 2) формы прилагательного степени сравнения (для качественных прилагательных); специфические суффиксальные формы словообразования; 3) функции прилагательного в предложении (приписывание существительному, предикативное значение прилагательного). Особенности числительного: 1) категориальное значение числа (кардинальное и порядковое); 2) узкий набор простых числительных; специфические формы образования сложных числительных; специфические суффиксальные формы образования порядковых числительных; 3) функции числительного признака и числительного субстантива.

Особенности местоимения: 1) категориальное значение указания (дейксис); 2) узкие множества различного статуса с соответствующими формальными свойствами категориальной изменчивости и словообразования; 3) субстантивные и адъективные функции для разных множеств. Особенности глагола: 1) категориальное значение процесса (представлено в двух верхних рядах форм, соответственно, как конечный процесс и нескончаемый процесс); 2) формы глагольных категорий лица, числа, времени, вида, залога, наклонения; противопоставление глагола конечные и нескончаемые формы; 3) функция конечного сказуемого для конечного глагола; смешанные глагольные — отличные от глагольных функции для нескончаемого глагола.

Особенности наречия: 1) категориальное значение вторичного свойства, т.е. свойства процесса или другого свойства; 2) формы степеней сравнения для качественных наречий; специфические суффиксальные формы словообразования; 3) функции различных адвербиальных модификаторов. Мы рассмотрели отличительные свойства именных частей речи, которые объединяют слова с полным номинативным значением, характеризующиеся самостоятельными функциями в предложении. Смысловым частям речи противопоставляются слова с неполным номинативным значением и несамостоятельными, посредническими функциями в предложении. Это функциональные части речи. По принципу «обобщенной формы» к функциональным частям речи традиционно относят только неизменяемые слова. Что касается их отдельных форм как таковых, то они просто представлены списком, поскольку количество этих слов ограничено, так что их нет необходимости выделять на какой-либо общей, оперативной схеме.

К основному функциональному ряду слов в английском языке относятся 6 служебных частей речи: артикль, предлог, союз, частица, модальное слово, междометие. Артикль служит для чёткого ограничения основных функций. Предлог демонстрирует зависимости и взаимосвязи между существительными. Конъюнкция (союз) указывает на связь явлений. Частица объединяет функциональные слова, которые придают уточняющее и ограничительное значение. К этому ряду, наряду с другими уточняющими словами, следует отнести отглагольные послелоги как функциональные модификаторы глаголов и т. д. Модальное слово, занимающее в предложении более или менее выраженную обособленную позицию, выражает отношение говорящего к отражаемой ситуации и ее частям. Сюда относятся функциональные слова, обозначающие вероятность (вероятно, возможно и т.д.), качественную оценку (fortunately, unfortunately, luckily, etc.-примеры даны по М.Я.Блоху), а также утверждения и отрицания. Междометие, занимающее обособленное положение в предложении, является сигналом эмоций. Каждая часть речи после ее идентификации подразделяется на подсерии в соответствии с различными семантико-функциональными и формальными особенностями составляющих ее слов. Это подразделение иногда называют «подкатегоризацией» частей речи.

Таким образом, существительные подразделяются на собственные и нарицательные, одушевленные и неодушевленные, исчисляемые и неисчислимые, конкретные и абстрактные и т. д. Глаголы подразделяются на полностью предикативные и частично предикативные, переходные и непереходные, деепричастные и статусные, фактивные и оценочные и т. д. М.Я. Блох приводит следующие их примеры: walk, sail, prepare, shine, blow — can, may, shall, be, become; take, put, speak, listen, see, give — live, float, stay, ache, ripen, rain; write, play, strike, boil, receive, ride — exist, sleep, rest, thrive, revel, suffer; roll, tire, begin, ensnare, build, tremble — consider, approve, mind, desire, hate, incline. Прилагательные подразделяются на качественные и относительные, имеющие постоянный признак и временный признак (последние называются «стативами» и выделяются некоторыми учеными в отдельную часть речи под названием «категория состояния»), фактивные и оценочные и т. д. Мы рассмотрели общую систему разделения лексики на части речи, разработанную современными лингвистами на основе традиционной морфологии. Известно, что разные авторы могут по-разному распределять слова по частям речи. Этот факт заставляет некоторых лингвистов сомневаться в рациональности классификации в целом и обвинять её в субъективности или «ненаучности». Однако такая критика является необоснованной. Когда мы рассматриваем классификацию частей речи, важно понимать, что основополагающие принципы определения класса слов являются более важными, чем случайное увеличение или уменьшение установленных групп или перераспределение отдельных слов из-за пересмотра их подкатегорий.

Идея подкатегоризации как необходимого второго этапа классификации говорит об объективности такого анализа. Например, предлоги и союзы могут быть объединены в одну категорию «связок», так как их функция — соединять смысловые элементы предложения. В таком случае на втором этапе классификации мы можем разделить расширенный класс связующих слов на два основных подкласса: предложные и союзные связки. Артикли также можно включить в более широкий набор частиц-определителей.

Как известно, существительные, прилагательные и числительные часто рассматриваются как один общий класс, называемый «имена».

В древнегреческой грамматике они не различались, так как имели одинаковые формы изменения (склонения). С другой стороны, в различных описаниях английской грамматики таким словам, как yes, no, местоименные определители существительных и даже местоимение it, предшествующее им, часто придается статус отдельного класса. Однако это не меняет их функциональную роль.. Важно помнить, что современные принципы выделения частей речи были разработаны в результате тщательных исследований, которые охватывали обширный материал из множества языков. Именно в советской лингвистике трёхкритериальная система частей речи была систематизирована и применена на практике с максимальной последовательностью.

Особо следует отметить трёх выдающихся лингвистов, которые внесли значительный вклад в развитие этих критериев: * В. В. Виноградов, который изучал русскую грамматику; * А. И. Смирницкий и Б. А. Илиш, занимавшиеся английской грамматикой. Помимо трёхкритериального подхода к разделению слов на грамматические классы, современная лингвистика также разработала более узкий принцип, основанный исключительно на синтаксических признаках слов.. Проблема, с которой сталкивается трёхкритериальный принцип, заключается в определении статуса части речи для слов, которые похожи на обычные, но имеют некоторые отличия. Эти слова играют важную роль в словосочетаниях и предложениях, выступая в качестве грамматических посредников.

К таким словам можно отнести модальные глаголы и их эквиваленты: супплетивные наполнители, вспомогательные глаголы, аспективные глаголы, усилительные наречия и определяющие местоимения. Сложность заключается в том, что эти слова обладают различными свойствами, которые могут пересекаться в определённых классах. Один из способов решения этой проблемы — выбрать один критерий из трёх как основной.

Интересно, что в древнегреческом грамматическом учении, которое заложило первые основы теории частей речи, деление слов на грамматические классы также основывалось только на одном определяющем критерии — формально-морфологических признаках. Это означает, что любое слово, которое подвергалось анализу, классифицировалось как лексема в зависимости от его связи с грамматическими изменениями. На начальном этапе изучения лингвистики и в контексте языков с высокой степенью флексии такая характеристика слов оказалась весьма эффективной. Однако на современном этапе развития лингвистической науки синтаксическая характеристика слов, которая стала возможной благодаря раскрытию их фундаментальных морфологических свойств, представляется гораздо более значимой и универсальной с точки зрения общих классификационных требований.

Эта характеристика имеет особое значение, поскольку она демонстрирует, как слова распределяются по различным категориям в зависимости от их функций в предложении.

В рамках данного подхода роль морфологии не умаляется, а, напротив, становится более понятной благодаря выявлению связей между категориальным составом слова и его значением в формировании высказывания. Эта характеристика считается более универсальной, так как она не ограничивается словоизменительными особенностями языка и, следовательно, может быть применена к языкам с разными типами морфологии. В русском языке принципы синтаксического подхода к классификации словарного запаса были разработаны А. М. Пешковским. Принципы синтаксической (синтаксико-дистрибутивной) классификации английских слов были сформулированы Л. Блумфилдом и его последователями З. Харрисом и особенно Ч. Фриз.

Эта классификация основывается на изучении сочетаемости слов с помощью тестирования на замену. В результате проведённых исследований была создана стандартная модель, которая выделяет четыре основные «позиции» смысловых слов в английском предложении: существительное (N), глагол (V), прилагательное (A) и наречие (D). Местоимения также включаются в эти классы, выступая в роли их заместителей. Слова, которые не занимают определённую позицию в предложении, рассматриваются как служебные, поскольку они выполняют различные синтаксические функции. Вот как Ч. Фриз представляет свою схему английских слов-классов [Fries].Для своих материалов он выбирает записанные на магнитную ленту спонтанные разговоры, содержащие около 250 000 слов (50 часов разговора The words isolated from this corpus were tested on three typical sentences (which were also isolated from the original records) and used as substitution test frames:

Frame A: The concert was always good.

Frame B: The clerk suddenly remembered the tax.

Frame C: The team went to that place.

Заключенные в круглые скобки позиции необязательны с точки зрения структурного завершения предложений. В результате последовательных тестов на замену приведенных «фреймов» были составлены следующие списки позиционных слов («словообразовательных форм» или «частей речи»):

Класс 1. (А) concert, coffee, taste, container, difference, etc. (Б) clerk, husband, supervisor, etc.; tax, food, coffee, etc. (В) команда, муж, женщина и т. д.

Класс 2. (А) был, казался, стал и т. д. (Б) запомнил, захотел, увидел, предположил и т. д. (В) пошел, пришел, убежал,. жил, работал и т. д.

Класс 3. (А) хороший, большой, необходимый, чужой, новый, пустой, etc.

Class 4. (А) там, здесь, всегда, тогда, иногда и т. д. (Б) четко, в достаточной степени, особенно часто, в ближайшее время и т. д. (С) туда, обратно, вон и т.д.; быстро, нетерпеливо, уверенно и т. д.

Все эти слова могут занимать позиции во фреймах не затрагивая их общего структурного значения (например, «вещь и ее качество в данный момент времени» — первый кадр; «субъект — действие — объект, на который воздействуют, — характеристика действия» — второй кадр; «субъект — действие — направление действия» — третий кадр). Повторяющиеся взаимозаменяемости при замене первоначально идентифицированных позиционных (т.е. условных) слов в разных словосочетаниях определяют их морфологические характеристики, т.е. характеристики, относящие их к различным подклассам идентифицированных лексемных классов. Функциональные слова (function words) выявляются в процитированном процессе тестирования как неспособные заполнить позиции фреймов без нарушения их структурного значения. Эти слова образуют ограниченные группы, насчитывающие в общей сложности 154 единицы.

Выявленные группы функциональных слов могут быть распределены по трем основным наборам. Слова из первого набора используются в качестве определителей смысловых слов. Сюда относятся определители существительных, модальные глаголы, служащие в качестве определителей смысловых слов. глаголы, функциональные модификаторы и усилители прилагательных и наречий. Слова второго набора играют роль межпозиционных элементов, определяющих отношения смысловых слов друг к другу. Сюда относятся предлоги и союзы. Слова из третьего набора относятся к предложению в целом. Таковы вопросительные слова (что, как и т.д.), побудительные слова (давайте, пожалуйста и т.д.), слова, привлекающие внимание, слова утверждения и отрицания, вводные предложения (it, there) и некоторые другие. Сравнивая синтаксико-дистрибутивную классификацию слов с традиционным делением по частям речи, мы вслед за М. Я. Блохом видим, что их общие схемы во многом похожи.

В обеих классификациях выделяются смысловые и функциональные слова, а смысловые слова делятся на четыре основных класса: существительные, прилагательные, глаголы и наречия. Числительные и местоимения не имеют собственной позиционной функции, но могут заменять существительные и прилагательные. Функциональные слова рассматриваются как синтаксические посредники, и их список формализован. Однако, несмотря на эти очевидные сходства, между двумя классификациями существуют и существенные различия. Их правильная оценка позволяет сделать важные обобщения о структуре лексической системы языка. Одна из главных истин, вытекающих из сравнения этих двух классификаций, заключается в том, что лексика языка чётко делится на понятийную и функциональную части. Характер смысловой части лексикона — открытый, а функциональной — закрытый, и это не считая промежуточного поля между ними. Данное различие приобретает строгий статус формального грамматического признака. Единство смысловых лексем ярко проявляется в межклассовой системе словообразования, которую можно представить в виде формального четырёхступенчатого ряда, пронизывающего весь лексикон и отражённого в регулярных фразеологических связях.

Согласно мнению М. Я. Блоха, в систему местоимений входят не только личные местоимения, но и местоименные наречия, а также глаголы-заменители, которые используются в тех же функциях. Также было установлено, что многозначные слова широкого значения образуют промежуточный слой между местоимениями и смысловыми словами. Эти многозначные слова тесно связаны с местоимениями благодаря своей способности замещать. Не нужно быть слишком умным, чтобы понять, что грамматическое число личных местоимений уникально и не похоже на количество обычных существительных. Обычно число существительного указывает на количество его референта: «один — больше, чем один» или, в более оппозиционной оценке, «множественное число — не множественное число». При этом качество референтов обычно не меняется с изменением числа (многочисленные исключения из этого правила не входят в нашу дискуссию).

Например, когда я говорю о нескольких пудреницах, я имею в виду ровно столько одинаковых предметов. Или, когда я упоминаю команду из одиннадцати футболистов, я имею в виду именно столько игроков в этой спортивной команде. Однако, когда речь заходит о личных местоимениях, ситуация меняется. И главная особенность этого различия заключается в том, что личное местоименное значение множественного числа неоднородно. Коммуникативные свойства предложений можно глубже понять, если обратиться к теории фактического членения предложения. Фактическое членение позволяет выразить информативное содержание высказывания с правильной градацией его частей в зависимости от их роли в контексте. Но любое высказывание формируется в рамках системы коммуникативных типов предложений.

Если мы сравним коммуникативную цель высказывания с его фактическим строением, то увидим, что каждое коммуникативное предложение обладает своими уникальными особенностями. Эти особенности особенно ярко проявляются в природе ремы — смыслового ядра высказывания. В строго декларативных предложениях мы непосредственно выражаем определённую мысль. Поэтому фактическое членение повествовательного предложения является наиболее полным и развёрнутым. Рема в таких предложениях занимает центральное место в высказывании. Это можно легко продемонстрировать с помощью вопроса-теста, который непосредственно раскрывает рематическую часть предложения. Например: «В следующее мгновение она узнала его». → «Что она сделала в следующее мгновение?»

Вопросительное местоимение «что» в этом примере ясно указывает на то, что часть « (узнал) его» является декларативной ремой, поскольку эта часть заключена в вопросительно-местоименную ссылку.. Другими словами, проверяемое высказывание с его законченным фактическим членением является единственным возможным ответом на заданный потенциальный вопрос. Говорящий произнёс это высказывание только для того, чтобы выразить, что его узнали. Ещё одним трансформационным тестом для определения декларативной ремы является логическое наложение. Логическая суперпозиция предполагает преобразование тестируемой конструкции в такую, в которой рема занимает позицию логически выделенного сказуемого. В качестве примера рассмотрим второе предложение из следующей последовательности: «И мне было очень не по себе. Меня одолевали всевозможные дурные предчувствия».

Логическое построение этого высказывания выглядит следующим образом: → «Меня одолевали всевозможные дурные предчувствия». Этот тест позволяет определить подлежащее высказывания «всевозможные предчувствия» как рему, так как именно эта часть высказывания оказывается в позиции сказуемого при суперпозиционном преобразовании. По мнению М.Я.. Блоха утверждает, что подобные диагностические процедуры помогают выявить многоуровневую структуру фактического членения в сложных синтаксических конструкциях. Например, в следующем сложноподчиненном предложении легко выделить три декларативные ремы на трех последовательных синтаксических уровнях, задав вопрос-тест с использованием ремы: «Я знал, что мистер Уэйд был очень взволнован тем, что он узнал» (У М. Я. Блоха в оригинале это звучит так: «I knew that Mr, Wade had been very excited by something that he had found out.»). Тест для первого синтаксического уровня: «Что я знал?» Тест для второго синтаксического уровня: «В каком состоянии был мистер Уэйд?» Тест на третий синтаксический уровень: «Что его взволновало?» (Или: «Чем он был взволнован?») В оригинале у М. Я. Блоха это выглядит так: «Test for the first syntactic layer: What did I know?

Test for the second syntactic layer: What state was Mr. Wade in?

Test for the third syntactic layer: What made him excited? (By what was he excited?)»

Строго императивное предложение, в отличие от строго декларативного, не предназначено для выражения какого-либо факта. Оно основано лишь на предположении, без его прямой формулировки. В императивных предложениях, побуждение к действию или его запрещение основывается на противопоставлении. Когда мы просим что-то сделать (утвердительное побуждение), мы предполагаем, что что-то не выполнено или не затрагивается желаемым действием. И наоборот, если мы просим не делать что-то (отрицательное побуждение), мы исходим из прямо противоположной предпосылки.

Fluffy: After reading all this information about the different parts of speech and how they are classified according to M. Ya. Bloch, I find it difficult to choose a point of view that would be most acceptable to all people learning English today.

Jasper: In order to better understand and absorb the material covered in the English theoretical grammar course, I would like to suggest that you do a small exercise.

Exercise 2. Answer the questions.

1.How many parts of speech are there in modern English, and what is M. Ya. Bloch’s approach to their classification? 2.What does it rely on? 3.Can data from cognitive linguistics be used to identify parts of speech?

Fluffy: Чтение — самый распространённый вид речевой деятельности в школе. Этому есть много причин. Ученики могут применять полученные умения чтения в повседневной жизни, и их формирование происходит быстрее и проще, чем умений говорения, письма и аудирования и сопутствующим им навыкам. В процессе обучения второму иностранному языку чтению часто уделяется особое внимание. Учителя используют проверенные методы обучения, которые показывают хорошие результаты. Это связано с тем, что в процессе чтения можно использовать уже имеющиеся знания и навыки. Особенности обучения чтению на втором иностранном языке заключаются в двух аспектах.

Первый — это обучение технике чтения, которое включает установление звукобуквенных соответствий и автоматизацию этих навыков. Этот процесс значительно ускоряется, если учащиеся уже владеют английским языком. Они знают латинский алфавит, и навыки чтения на английском языке облегчают им звукобуквенный анализ и синтез. Однако даже для старшеклассников может быть сложно самостоятельно анализировать звукобуквенные соответствия в английском языке из-за сложной системы буквосочетаний и необходимости использовать транскрипцию. Это может замедлить автоматизацию навыков, если у учащихся нет возможности дополнительно проработать сложные действия и операции. Кроме того, учащиеся сталкиваются с интерферирующим влиянием родного языка.

По этим причинам необходимо использовать специальные упражнения для отработки техники чтения на английском языке. При обучении технике чтения на английском языке как иностранном наиболее эффективным методом является имитация фраз и небольших текстов, записанных на плёнку. Это позволяет учащимся одновременно осваивать мелодику языка. Такая работа должна дополняться упражнениями на тренировку чтения особо сложных буквосочетаний. В процессе обучения чтению на иностранном языке важно сочетать отработку техники с коррекцией произношения соответствующих звуков. Ещё одна особенность обучения чтению на иностранном языке связана с повышением эффективности и интенсификацией процесса. В программных документах навыки, составляющие умение чтения, рассматриваются не только как цель обучения, но и как средство для развития речевых умений говорения и письма.

Письменный текст служит образцом, наблюдение за коммуникативной организацией которого помогает создавать собственные устные и письменные тексты. В процессе понимания текста читатель реконструирует его смысл. Каждый этап этой реконструкции требует мыслительной активности: узнавания, предвосхищения, проверки, сортировки и так далее. Интерпретативный потенциал чтения позволяет развивать умение создавать собственные тексты.

Это становится возможным благодаря пониманию особенностей организации «чужих» текстов. Чтобы обучение иностранному языку проходило более эффективно, методика формирования навыков чтения должна сочетать в себе два аспекта: * Обучение непосредственно чтению и пониманию текста. * Интерпретацию текста как продукта речевой коммуникации с целью создания подобных текстов в устной или письменной форме. Для развития речемыслительных навыков, образующих комбинированное умение чтения, мы предлагаем вам познакомиться с романом «Alligator» американской писательницы Shelley Katz. Книга была издана в 1977 году в Нью-Йорке издательством Dell и насчитывает 331 страницу.

Exercise 3. Answer the questions.

1.The methodology of developing reading skills: what does it consist of? 2. Do the systems of exercises for teaching reading techniques in the first and second foreign languages differ? 3.What reading skills should be developed when teaching students a second foreign language?4. How to build an effective system of exercises for teaching reading skills?

Fluffy: Let’s talk about alligators. Read and retell the following sentences borrowed from «Alligator» by Shelley Katz.

Prologue

They tell grim tales (мрачный, зловещий рассказ или сказка) of him all along the Florida Everglades (Национальный парк Эверглейдс). Blacks tell of a gator (крокодил) as big as an elephant that eats little children and attacks men in boats with the power and ferocity (свирепость) of a landlocked (закрытый) Moby Dick (Белый кит-произведение Германа Мелвилла). Whites in the small towns that border (граничить) the swamps (болота) have hunted him for years. They tried to kill him with axes (топорами), shotguns (карабинами, дробовиками, охотничьими ружьями), and hooks (багор, крюк).They say he has suffered (страдать, болеть) hours of agony from the wounds (раны) they have inflicted (нанесённые, причинённые); many times he has been close to death at their hands. В данном отрывке встречается множество стилистических приемов и выразительных средств, которые создают атмосферу страха и драматизируют рассказ о загадочном существе. Давайте рассмотрим основные из них:

Эпитеты: Слова «мрачные сказки» и «свирепость» задают эмоциональную окраску текста, подчеркивая зловещий характер рассказов о существе. Эпитеты усиливают шок от описания и акцентируют внимание на негативных эмоциях и ассоциациях.

Сравнение: Сравнение крокодила с «городским Мoby Dick» создает яркий и запоминающийся образ. Оно связывает ко всемирно известному стандарту силы и величия, который усиливает опасность крокодила, и привлекает внимание читателя на уровне культурного контекста, показывая масштаб и интенсивность угрозы.

Перечисление: Описание способов охоты на крокодила — «топорами, карабинами, дробовиками, баграми» — создает массивность усилий, прикладываемых к уничтожению существа. Перечисление усиливает представление о длительной борьбе человека с природой, а также раскрывает различные методы, применяемые людьми.

Персонификация страданий: Фраза «он страдает часы агонии» предполагает, что крокодил не просто жертва обстоятельств, но и воспринимаемое существо с интеллектуальным состоянием. Это углубляет эмоциональную связь читателя с крокодилом и добавляет ему человеческого аспекта.

Эмоциональная напряженность: Использование слов «агонья» и «близкое к смерти» создает атмосферу страха и жалости, подчеркивая хрупкость существа и его уязвимость, что заставляет читателя переживать за его судьбу.

Контраст между культурами: Упоминание о «черных» и «белых» рассказах подчеркивает различия в восприятии одной и той же фигуры в контексте разной культуры. Этот элемент создает ощущение многослойности рассказа и показывает, как мифология о крокодиле обретает разные формы в зависимости от культурных условий.

Визуальные образы: Описание крокодила как «огромного, как слон» создает впечатляющий и запоминающийся образ, который усиливает страх перед этим существом. Это помогает читателю визуализировать масштаб угрозы и мощь крокодила.

В целом, отрывок погружает читателя в атмосферу мифологии и ужасов, связанных с существом, представляющим собой как физическую, так и культурную угрозу. Эти выразительные средства и стилистические приемы работают на создание образа крокодила не только как животного, но и как символа страха, страдания и конфликта между человеком и природой.

Exercise 4. Working with text and dictionaries

1. Найдите в словаре верный перевод клише: " to kill him with axes». 2. Выберите в тексте верный перевод клише: «страдать, мучиться часами в агонии». 3. Найдите в словаре верный перевод клише: " close to death». 4. Приведите верный перевод клише: " attack with the power and ferocity». 5. Дайте верный перевод клише: " at their hands». Выберите в тексте пример, иллюстрирующий стилистический прием «антономасия», если таковой имеется. Объясните Ваше мнение.6. Выберите пример, иллюстрирующий стилистический прием «метафора» из текста. 7. В каком стиле написал анализируемый пролог к роману «Аллигатор» Шёли Кац?

Azure: Interestingly, many scientists have attempted to define the word as a linguistic phenomenon. However, none of the proposed definitions can be considered entirely satisfactory in all respects. Surprisingly, despite the advances of modern science, certain important aspects of the nature of the word remain hidden from us. We also do not fully comprehend the phenomenon of language, which relies on words. Our knowledge of the origin of language, and thus the origin of words, remains limited. Indeed, there are numerous hypotheses, some of which are as fantastic as the theory of divine origin of language. We do not understand the mechanism by which thoughts are transformed into combinations of sounds known as «words». We also do not comprehend how the brain of the listener converts acoustic signals into concepts and ideas, establishing a two-way communication process. Lexicological research addresses these and numerous other questions. Lexicology is a branch of linguistics dedicated to the study of words. Lexicology, the study of words and vocabulary in any language, is an important part of general linguistics. Each individual language has its own unique vocabulary, which is studied in the specific lexicology of that language.

This course focuses on the lexicology of Modern English, or the specific vocabulary of the English language. Each particular lexicology is based on the principles of general lexicology. Therefore, in the first chapters of the course, some general lexicological problems are discussed, such as the theory of the word and the main aspects of the study of meaning and the semantic structure of words — semasiology. The lexicology of any language, including English, can be divided into historical lexicology, which examines the origin and evolution of its vocabulary, and descriptive lexicology of the contemporary language, which analyzes its vocabulary at the current stage of its development, highlighting its unique features compared to other languages’ vocabularies. It is important to note that the vocabulary of a contemporary language exists as a complex system of interconnected elements that evolve over time. Therefore, it can only be fully understood with this development in mind. Therefore, although the descriptive lexicology of modern English has its own specific tasks that differ from those of historical lexicology, it cannot exist in isolation from the latter. For these reasons, this course on descriptive lexicology of modern English focuses not only on the current state of its vocabulary but also, to some extent, on the ways in which it is formed.

The study and description of the language system at a particular stage of its development is known as synchronic analysis, while the study of the historical evolution of its elements is known as diachronic analysis. It is crucial to make a clear distinction between synchronic and diachronic approaches and to choose an appropriate balance between them in any linguistic analysis. Considering the vocabulary of modern English as a system with specific features that evolve over time involves describing various types of words and their formations, as well as describing word equivalents — that is, various stable combinations.

A description of the fate of foreign language borrowings and their role in enriching the vocabulary of the English language, as well as an analysis of various lexical groups and layers in modern English, such as book and colloquial vocabulary, terms, slang words, neologisms, archaisms, and so on, and finally, an analysis of semantic relationships between words (synonyms and antonyms). As you know, the English vocabulary has been described in detail in numerous and diverse dictionaries. Therefore, familiarization with the rich English lexicography and the principles of dictionary compilation is also essential when studying the English vocabulary. It should be noted that lexicology does not study all words in a language equally, but focuses primarily on significant words. These include words that name objects, phenomena, and actions in the objective world.

For example: child, face, pen, big, new, nice, past, love, well. Service words are used to express relationships and connections between objects and events. These include prepositions, conjunctions, auxiliary verbs, and connectives. The difference between significant and service words will be discussed in more detail later; for now, it is enough to note that significant words have one or more meanings, while service words have a grammatical function that is often (but not always) connected to their meaning.

Some people might find word analysis uninteresting. However, with the right approach, it can be just as exciting and new as exploring the mysteries of the universe. We have a limited understanding of how words are related to their meanings. If we assume that there is a direct link between a word and its meaning, which seems reasonable, then we must ask how to explain the fact that the same object can have completely different names in different languages. Now, we know, albeit not with certainty, that there is no randomness in language. Every word is part of a complex, efficient, and well-balanced system. However, we do not understand why this system possesses these qualities, and our knowledge of how it formed is limited.

The list of our uncertainties could continue, but perhaps it’s time to approach the issue from a different angle and highlight some points we do know about words. Firstly, we know that words are the fundamental units of speech used for communication between individuals. Therefore, words can be seen as tools for communication. On the other hand, a word can be thought of as a collection of sounds that make up its meaning. The science of vocabulary — lexicology arose on the basis of the real needs of the linguistic practice of society, especially lexicography, literary creativity, literary criticism and the development of scientific terminology. The doctrine of the word and its meaning developed within the framework of philosophy.

Questions of the theory of the word, the relationship between the name and the denoted, have been throughout the history of philosophy one of the important elements of the problem of the relationship of thinking to being, and therefore turned out to be key issues in the struggle between materialistic and idealistic trends in philosophy. The lexicology of the English language as a whole is a poorly developed field, although there is quite an extensive literature on certain issues of it, both in Russian and English, as well as in German, French, Danish and other languages. Much attention is paid to vocabulary in works on the history of the English language, although historical phonetics and morphology usually occupy a leading place in them.

The etymological composition of English vocabulary, i.e. the origin of words, is the subject of fundamental work by a major representative of the older generation of English philologists, Walter Skeat, the compiler of the most famous English etymological dictionary. As mentioned above, lexicology has been a part of grammar for a very long time. In particular, grammarians dwell in detail on word formation, which is completely understandable, since this latter is essentially a borderline area between grammar and lexicology. In particular, the problem of word formation is examined in great detail in one of the books of the multi-volume work of the famous Danish linguist Otto Jespersen and in the book of the English grammarian Henry Sweet.3The work of the German scientist Herbert Kotsiol, which is specially devoted to word formation in the English language and contains a very rich factual material, is very well known.

The principles of consideration of lexical phenomena naturally changed due to the change in the general theoretical views of linguists. In the 19th century, the attention of vocabulary researchers focused on morphological, phonetic and semantic changes occurring in individual words and on the causes of these changes, which were seen in phenomena of an extra-linguistic order. Thus, representatives of the school «Words and Things» («Sachen und Wörter») founded by the Austrian scientist Schuchardt were mainly interested in the appearance of new words in connection with changes in the culture and way of life of the people. Representatives of the younger grammatical trend interpreted changes in vocabulary as a set of losses and additions caused by individual psychological factors. In the field of semantics, the main attention was paid to the classification of types of meaning changes, their causes and the conditions in which they occur. In the XX century, after the work of the Swiss scientist F. de Saussure,1 who proposed the separation of the historical study of language (diachrony) from the study of the static state of the language system, in which all elements are interconnected and mutually conditioned (synchrony), various schools and directions appeared that set themselves the task of studying language only in synchronic terms and in the system. In Soviet linguistics, both the confusion of descriptive and historical linguistics and the gap between them have been overcome, and the vocabulary is considered as a kind of system operating at this historical stage, which, however, is in a state of continuous development.

There are many monographic works and dissertations written by Soviet, English, American, French, German and Danish scientists and devoted to various individual problems of the development of the vocabulary of the English language, for example: borrowings, word composition, semantics (i.e., changing the meanings of words, ambiguity, classification of types of meaning changes) and even the history of individual words or groups words. As for the general works on the lexicology of the modern English language, such works are few and have a rather elementary character. Such are, for example, the famous books of the pioneer of English lexicology Trench, Greenow and Kitridge, McKnight, Partridge, Weekley, Sherd and many others. These works provide a lot of valuable factual material, but for all their entertainment they cannot satisfy the modern reader due to some methodological shortcomings common to all of them, namely: 1) They deny the regularity in the development of vocabulary and ignore the consistency and national identity of the language, including on equal grounds the changes that occurred in the word in English and beyond. They consider the history of language mainly as a collection of individual interesting or funny facts, and limit themselves to stating them.

This is confirmed even by the titles that the authors give to their books: E. Partridge — «The Fun of Word History», E. Weekley — «The Romance of Words». 2) Distort the connection between the history of language and the history of society, put the development of the dictionary in connection with the history of culture, but little connect it with the economic and political life of the people, exaggerate the importance of the individual psychological factor. 3) Reduce the process of enriching the vocabulary of a language to the penetration of all kinds of foreign borrowings into it, and when studying borrowings, they are interested only in the source from which a particular word got into the language, without paying attention to the peculiarities of its assimilation in the language that borrowed it.

Exercise 5. Answer the questions.

— 1. Что такое лексикология? 2. Какие учёные внесли вклад в развитие лексикологии? 3. Какие определения слова существуют в настоящее время? 4.Кто их автор? 5. В чём отличие лексикологии от грамматики, фонетики?

(Урок №2/Lesson 2)

Charles: Classification of vowels and consonants of the English language. Vowels. Speech sounds are divided into vowels and consonants. There are 20 vowels and 24 consonants in English. An exhaled stream of air, meeting tense and close vocal cords on its way, leads them into a state of periodic oscillation, resulting in a voice or musical tone. If the air stream does not encounter a noise-forming barrier in its path, sounds called vowels are pronounced.

The characteristic timbre of a vowel is determined by the volume and shape of the oral and nasal cavities, which serve as resonators. American, English and Russian researchers of the phonetic structure of the English language have repeatedly tried to create a classification of vowels. The proposed classifications differed significantly from each other, since different initial principles were taken as the basis: the position of the lips and tongue, longitude and brevity, simple and complex structure.Depending on the stability of articulation, vowel sounds are divided into monophthongs, diphthongs and diphthongs. Monophthongs (monophthongs [«mɔnafθɔŋz]) are vowels, when pronounced, the organs of speech remain motionless, the quality of the vowel is stable. There are 10 monophthongs in English: [ɪ], [e], [æ], [υ], [ɔ], [ɔ ׃], [a: ], [a: ], [a], [ʌ].Diphthongs are vowel sounds, with the articulation of which there is a smooth transition from one mode of speech organs to another, since diphthongs consist of two elements representing one phoneme.

The first element of the diphthongs is called the nucleus, and the second is a sliding appendage or glide. The emphasis falls on the core of the diphthong. There are 8 diphthongs in English: [eı], [aı], [ɔı], [aʊ], [çə], [eə], [əə], [ʊə].Diphthongoids (diphthongoids [«dɪfθɔngɔɪdz]) are vowel sounds, during articulation of which there is minimal movement of the organs of speech from one sound to another, since the constituent parts of the diphthongoid are very similar in nature and in the method of articulation. Diphthongoids occupy an intermediate position between monophthongs and diphthongs. There are 2 diphthongs in English: [ɪ: ], [u:].Triphthongs (triphthongs [’trıfθɔŋs]) are complex vowel sounds consisting of three vowel sounds combined in one syllable. The first element of triphthongs is always stressed and is the «strongest» component, the second is the third element, while the middle sound, being the weakest component, often falls out in fast or careless speech. Some phonetists believe that sounds such as triphthongs are missing from the English language, since, in their opinion, triphthongs are a combination of diphthongs and a neutral sound.

Therefore, they are defined as a complex sound. There are five triphthongs: [auə], [aıa], [əuə], [eıa], [ɔıa]. If we classify vowels according to the position of the bulk of the tongue in the oral cavity, then they can be divided into: the vowels of the front row (fully front vowels) are [ɪ: ], [e], [æ], and the kernels of the diphthongs [eı], [eə]; the vowels of the front-retracted row (front-retracted vowels) are [ɪ] and the kernels of the diphthongs [ɪə], [au], [aı];the vowels of the mixed series (mixed vowels) are [a: ], [a] and the core of the diphthong [au]; the vowels of the back advanced row (back advanced vowels) are [υ], [ʌ] and the core of the diphthong [uə]; vowels of the back row (back vowels) — [u: ], [ɔ׃], [ɔ] [a: ] and the core of the diphthong [ɔɪ]. When pronouncing the vowels of the first and second groups, the front part of the tongue is raised towards the alveoli and the hard palate. Vowels of a mixed series are pronounced with a uniform raising of the back of the tongue. When pronouncing the vowels of the fourth and fifth groups, the back of the tongue is raised to the soft palate.

If we characterize the vowels, taking into account the vertical movement of the language, i.e. to make a classification according to the degree of elevation of the language, then it appears in the following form: high-pitched vowels (close) — [ɪ: ], [ɪ], [υ], [u: ] [üə], [uə]; The vowels of the middle rise (mid-open) are [e], [a: ], [a] [eı], [eə], [au]; low-pitched vowels (open) are [æ], [ʌ], [a: ], [ɔ], [aı], [aʊ], [ɔı]. In each of these subclasses, narrow and broad variations are distinguished: high rise — narrow version: [i: ], [u: ]; Wide variant: [ı], [ʊ] [ıə], [uə]; The average rise is a narrow variant: [e], [a: ], [ɔ: ], [a: ]; Wide version: [a] [eə]; Low rise — narrow option: [ʌ], [ɔı]; wide variant: [ᴂ], [a: ], [ɔ], [aı], [aʊ]. According to the position of the lips, all vowels are divided into: rounded, or labialized (rounded): [ɔ: ], [ɔ], [u: ], [υ]; uncirculated or non-rounded: [ɪ], [ɪ: ], [e], [æ], [a: ], [a: ], [a], [a], [ә]. The longitude (or quantitative) characteristic of vowels depends on the duration of the sound of their positional variants in speech.

The English language differs: long vowels: [i: ], [u: ]; [ɔ ׃], [a: ], [ə: ]; short vowels: [ı], [e], [ᴂ], [ɔ], [ʊ], [ʌ], [ə]. According to the degree of tension of the muscles of the speech apparatus, vowels are divided into tense (all long vowels) and unstressed (all short vowels). Diphthongs can be considered semi-stressed, because by the end of their utterance, muscle tension decreases. Each vowel sound in the IPA (International Phonetic Association) transcription system was given a corresponding number. The whole system looks like this: No.1 — [i: ], No.2 — [i], No.3 — [e], No.4 — [ᴂ], No.5 — [a: ], No.6 — [ɔ], No.7 — [ɔ: ], No.8 — [ʊ], No.9 — [u: ], No.10 — [ʌ], No.11 — [a: ], No.12 — [a], No.13 — [eı], No.14 — [aı], No.15 — [aı], No. 16 — [Aʊ], No.17 — [ɔı], No.18 — [ıə], No.19 — [eə], No.20 — [ʊə].

Exercise 6. Answer the questions.

— 1. На какие виды подразделяются звуки речи? 2. Сколько гласных и согласных в английском языке? 3. На какие группы в зависимости от стабильности артикуляции подразделяются гласные звуки? 4. Как можно классифицировать английские гласные звуки по положению основной массы языка в ротовой полости? 5. Как можно охарактеризовать гласные звуки по степени подъема языка?

Jasper: In order to improve that knowledge I’ll give you some more information about A Grammar of Modern English Usage: English parts of speech. Words of the English language may be grouped into word classes called «parts of speech» (Слова английского языка могут быть сгруппированы в классы слов, называемые «частями речи»). Each part of speech has a set of features: semantic, morphological and syntactic, typical of this particular class of words (Каждая часть речи обладает набором признаков: семантических, морфологических и синтаксических, характерных для данного конкретного класса слов). In accordance with these criteria (semantic, morphological and syntactic) English words form the following classes: the Noun: it is used to name physical objects (concrete nouns) or abstract notions (abstract nouns), the adjective, the adverb, the pronoun, the numeral, the preposition, the conjunction, the verb (В соответствии с этими критериями (семантическими, морфологическими и синтаксическими) английские слова образуют следующие классы: существительное, прилагательное, наречие, местоимение, числительное, предлог, союз, глагол).

Глаголы в английском языке могут изменяться по временам и времён много. Приведём пример одного из них– Present continuous (I am doing): We use the present continuous tense to talk about actions that are happening at the moment of speaking. For example:

— Please don’t make so much noise. I’m studying.

— Let’s go out now. It’s not raining anymore.

— Where is Margaret?

— She’s taking a bath. — (At a party) Hello Ann. Are you having a good time at the party?

Study this example situation: Ann is in her car. She is on her way to work. She is driving to work. This means: she is driving now, at the time of speaking. This is the present continuous tense.

The description of each part of speech given below is based on these above-mentioned criteria (Описание каждой части речи, приведённое ниже, основано на этих вышеупомянутых критериях).

Exercise 7. Answer the questions.

— 1. Can you tell me about the different parts of speech in English grammar? 2. What exactly are nouns, and how do they function in sentences? 3. Are there any differences between concrete and abstract nouns, and if so, what are they? 4. In terms of grammatical meaning and categorical features, how do verbs differ from nouns? 5. Could you please describe the present continuous tense in English, and when it is used?

Fluffy: Let’s continue our discussion about alligators. Here is an abstract from «Alligator» by Shelley Katz that we can read and discuss.

Prologue

Huge (огромные) chunks (куски) of flesh (мяса, плоти, тела) have been torn (были вырваны) from his leathery sides (от его кожистых боков), and his monstrous dragonlike head (чудовищная драконья голова) is riddled with (изрешечена, пронизана, испещрена) the lead (свинцом) of their shotguns (ружей) and the steel of their rifles (сталью их винтовок). But still he has survived (Но всё же он выжил). He has survived because, in some mysterious way, the people want him to (Он выжил, потому что каким-то таинственным образом этого хотят люди). He is a legend (Он — легенда). And there are very few legends left (И легенд осталось очень мало). В этом отрывке автор использует разнообразные стилистические приемы и выразительные средства, чтобы создать впечатляющий образ существа, которое одновременно вызывает страх и восхищение. Давайте рассмотрим основные элементы, использованные в тексте:

Эпитеты и прилагательные: Словосочетания «огромные куски», «чудовищная драконья голова», «кожистые бока» передают физическую мощь и ужас существа, формируя образ, который вызывает одновременно интерес и страх. Эпитеты помогают создать впечатление о том, как это существо отличается от обычных, подчеркивая его необычность и атрибуты монстра.

Метафоры: Фраза «изрешечена свинцом» подразумевает сильный удар силы человека против этого существа, что подчеркивает его стойкость и мужество. Это создает контраст между человеческим насилием и почти сверхъестественной чем-то способностью существа выживать.

Синтаксический параллелизм: Структура предложений «But still he has survived. He has survived because, in some mysterious way, the people want him to» создает ритм и подчеркивает главную идею о выживании. Этот прием усиливает акцент на последующих рассуждениях о легенде и желании людей сохранить это существо.

Ностальгический тон: Выражение «очень мало легенд осталось» создает ощущение утраты и печали, подчеркивая значимость выживания этого существа, которое олицетворяет нечто большее, чем просто биологическая форма жизни. Это разрушение историй и мифов вызывает у читателя чувство тоски по чего-то полноценному и великому.

Персонификация: Слово «легенда» воспринимается как живое существование, имеющее свои собственные желания и основные качества. Это придает отрывку глубину и обозначает, что это не просто существо, а символ чего-то важного и значимого в человеческом опыте.

Антитезис: Противопоставление между «травмами» существа и его «выживанием» создает драматичность. С одной стороны, оно изгнано, но с другой — исторически и культурно обосновано, так как желания людей сохранять этот миф подтверждают его значимость.

Краткость: Предложения выстраиваются таким образом, чтобы передать информацию лаконично. Это создает эффект immediacy, что помогает читателю быстрее войти в суть проблемы, которые обсуждаются в произведении.

В целом, этот отрывок задает тон для дальнейшего повествования, заставляя читателя задуматься о символическом значении существа и о том, почему оно осталось в сознании людей как легенда. Это одновременно вызывает любопытство и опасение, создавая богатую основу для дальнейшего развития тем в произведении.

Exercise 8. Decide whether the following sentences are true or false. If they are false, correct them.

— 1. Huge chunks of flesh have been torn from his leathery sides — False. 2.He is not a legend. 3.There are very few legends left — True. 4.Unfortunately, he has survived after being wounded — False. 5.There are five hunters who managed to kill an alligator — False. 6.His monstrous dragon-like head is riddled with lead from their shotguns and steel from their rifles — False. 7.Last Sunday, we went to the zoo to see a huge alligator described by Shelley and Paul Katz in their novel — False. 8. The people want him to appear again — False.

Azure: Recently, teachers of foreign languages have placed increasing emphasis on the fact that learning a language without knowledge of its culture is not sufficient for effective communication between representatives of different nationalities. In order to have a full-fledged conversation, it is essential to be aware of the other person’s culture, so that both parties can achieve mutual understanding.

From the perspective of cognitive science, one of the main reasons why it can be difficult for people to learn a new language is due to differences in language thinking between different cultures. Meanings in natural language are mentally encoded structures: from the point of view of American linguists, the founders of this trend (George Lakoff, Ronald Langacker, Ray Jakendorf), the meaning of an utterance is interpreted in consciousness, and is not outside of us, in the world around us, according to traditional ideas. linguistics. In this regard, the theory opposes both an ontological concept (the meaning of the word «DOG» is the totality of all dogs in the world), and a logical concept (the meaning of the word can be described by a set of general abstract semantic components), an epistemological concept (meaning is the establishment of the truth of our symbols in relation to the objective world).

According to these scientists, meaning is the interpretation by a native speaker of a certain conceptual content, the product of the interaction between the signal from the outside and the internal apparatus of thinking. Language is the conceptualization of the world, that is, the structuring of world chaos by our brain. In fact, this is a theory — a theory of understanding and using language, not its structure or functioning. J. Lakoff: linguistic meaning is a conceptual structure in the brain, «AN IMAGE is a SCHEME created as a result of interaction with the outside world: it’s a repetitive dynamic pattern of perception.» our perceptual processes and motor programs connect and structure our experience.» The CONTAINER layout is the concept of a border separating the inside from the outside. It is formed on the basis of experience: our body is a CONTAINER, and the difference between the EXTERNAL and INTERNAL matters to us. Hence the METAPHOR of expansion: we are container objects, we expand this relationship by association with other objects in our experience (MIND is a CONTAINER). Similarly– PART/WHOLE, SOURCE — PATH — GOAL.Against this background, cognitive semantics is built — an explicit, empirically grounded subjectivist, or conceptualist theory of meaning [Langacker 1990: 315], which accepts that the meaning of an expression cannot be reduced to an objective characterization of the situation described by the utterance: no less important is the angle chosen by the «conceptualizer» when considering the situation and for expressive portraying her. The full semantic characteristic of the expression is established on the basis of such factors as the level of concreteness of perception of the situation, background assumptions and expectations, the relative isolation of specific units and the choice of point of view (perspective) on the described scene.

The invariant is the prototypes (playing the role of end stops) and the terms closest to the prototypes. As a general theory of categorization, cognitive semantics is interdisciplinary, is not limited only to the linguistic aspect, and therefore comes into contact with modern epistemological concepts, especially those where the concept of intentionality is brought to the fore. It also has an anti-structuralist orientation, which brings it closer to philosophical deconstructivism (Derrida). Its basic principles:1) in the foreground are the epistemological functions of specific entities within the framework of the structure, and not the system of oppositions (as in structuralists); 2) the cognizing subject — the carrier of copulation — is an active principle that generates the meanings of expressions, and does not take them ready-made from nature; 3) the interpretations of the expression are not equal, some are more preferable already due to the properties of the language of the selected expression. The human way of conceptualizing the world leads to a significant discrepancy between the actual properties of objects of reality and how they are represented in language. This is due to the fact that a person divides the world according to his needs, and at the same time does not care at all about the scientific reliability of the data obtained by him in the practical experience of encountering things. This is especially true for the perception of space and the characteristics of objects in it. It is no accident that L. Talmi believes that the geometry of Euclid, which linguists learned at school, and related to concepts such as size, distance, length, angle, etc., is not relevant to the linguistic conceptualization of the world. In language, a person does not measure individual parameters of an object, but the entire object, referring it to one or another topological type (round, flat, elongated, shapeless objects, etc.).

At the same time, the linguistic conceptualization of the world has the ability to combine logically incompatible things. So, it turns out that objects can have «negative parts» (negative parts). The usual parts are the «added» substance, and the negative is the «taken out» of the object, cf. hole, opening and under. as negative parts of objects such as a pit, a door, a cave, etc. The same indifference to matter and substance is manifested in language when the same object receives several linguistic representations at the same time. A good example of this kind is lake — type lexemes, which actually denote capacity (cf. in a lake), but, for example, in such combinations as by lake, they completely lose their volume (thickness) and turn out to be a plane [cited by: Rachilina 1998: 285—286]. An example of how in the linguistic conceptualization of the world the same object can change its «dimension» from a two-dimensional representation to a three-dimensional one is the observations of E.V. Uryson on the meaning of the Russian word sky. The sky token designates both the airspace itself high above the ground, and the dome that visually restricts it. In other words, from the point of view of the Russian linguistic picture of the world, the sky is a three-dimensional object with a surface. This idea is partly traced in the compatibility of the sky lexeme with spatial prepositions. Cf. There are birds in the sky <parachutists> [as in space], but there are stars in the sky [as on the surface]; impossible *There are birds in the sky <parachutists>, because these objects are located significantly below the dome, as if covering the earth.

The paradox of the sky lexeme is that, although it designates a certain object entirely as a «three-dimensional» one, in a number of contexts it also implements a «two-dimensional» model of this representation as part of this object. It turns out that from the point of view of the modern Russian language, the «parts» of the sky and the sky itself are equal [Uryson 230—232]. As G.I. Kustova writes, non-linguistic reality is reflected selectively by a person. He creates a specific model of the situation or scheme. The source of the word’s meaning is the situation. However, the word does not contain all the information about the situation it designates. This follows at least from the fact that the same situation can be denoted by different words. For example, members of synonymous series represent the same action in different ways, highlight and emphasize different aspects and elements of the content of the situation. A word in a certain meaning, «choosing» only a part of information from a situation, gives a certain way of conceptualizing, understanding this situation — in other words, it is a semantic model of the situation, and, like any model, emphasizes something, highlights, if you like, sticks out, and darkens something, pushes it to the background the plan or even distorts it.

Therefore, the other side of the coin is no less important — the remaining information that was not included in the «main», initial value (or in the assertive part of the value). After all, the word, being a sign of the situation, connects a person with this situation. And although the word itself contains only part of the information about the situation, it provides access to a much richer and more meaningful information structure — a data bank, so to speak. And it is also a means of «realizing» the remaining information, «extracting» it and using it in derived values [Kustova 2004: 35—38]. It is important that the conceptual structures generated in this way have a «highlighted» (more precisely, highlighted in the sign) part (accent, dominant) and there is a «shadow» part («remainder»). At the same time, the ratio of the accentuated and the «shadow» part of the conceptual structure, or scheme, of the same situation has national specifics in different languages. So, in Russian verbs with the semantics of a transport trip, the method of further action after penetration into the vehicle is emphasized (boarding the bus, even if I stand there): take the subway.

In English, the highlighted part is the zone of the causer, its active action («take’, although it does not take anything): take the metro. It is specific for the Russian language to emphasize the excessive implicit representation in the verb of being on the surface of the image of the object located there: The glass is on the table, but the book is on the table. In Western languages, it is more natural to convey the general idea of finding (There is…). Anthropocentrism literally permeates all levels of the organization of the language system and its implementation in speech. In vocabulary, as in the operational environment of direct interaction of human experience with non-linguistic reality, anthropocentrism manifests itself in the most diverse and, so to speak, everywhere. The main categories of the lexical system are deeply anthropocentric — synonymy, antonymy and mainly polysemy. G.I. Kustova writes that «the reason for the very existence of polysemy in natural language is cognitive: polysemy is one of the main means of conceptualizing new experience. A person cannot understand the new without having some kind of «given», so he is forced to use the «old» signs and adapt them to new functions, extend them to other situations» [Kustova 2004: 11]. New meanings are constantly appearing in the language, and some of them disappear before they even get into the dictionary. This means that a person has a «generative» mechanism — a SEMANTIC mechanism.The structure of this mechanism, in turn, is connected not only with the immanent laws of language as a system of signs, but also with the immanent laws of language as a system of signs. Language is a part of a person.

If the metaphor of a mechanism is applicable to it, then with clarification: it is a NATURAL mechanism. The principles of its structure and functioning are consistent with human nature — and are subject to the same laws and the same restrictions as other internal mechanisms and human information systems. Since language addresses the world and «describes» the world, the number of meanings in language, generally speaking, is not limited by anything, except for human needs and his ability to store and retrieve these meanings from memory. At the same time, ALL the meanings, of course, are DIFFERENT, since they correspond to different non-linguistic realities. Two identical values are the same value. But since language is a part of a person, the number of WAYS to form meanings cannot be infinite, and these ways cannot be «any», whatever. It is impossible to imagine that the mechanism, even if it is «natural», would work completely chaotically, without any rules, so that each new value would be created using a unique technology. This is completely contrary to the principle of simplicity, the principle of economy, and, finally, just common sense. It is more natural to assume that there is a finite (and apparently foreseeable) number of countriesTAGS for the formation of values and TYPES of values. The MODEL (type) of a value is, among other things, also a method of packaging, a cognitive model of an object or situation. And no matter how changeable and diverse the extra-linguistic reality is, a person, for obvious reasons, is forced to use a limited set of tools to master this reality. But the main reason for polysemy is cognitive: a person understands the new, undeveloped through the given, mastered and known, models new objects and situations with the help of semantic structures already available to him, «bringing» new elements of experience under the mastered models [Kustova 2004: 20—23].

The same cognitive reason, due to the experience of human interaction with non-linguistic reality, lies at the heart of polysemy. Non-linguistic reality is reflected selectively by a person. He creates a specific model of the situation or scheme. The source of the word’s meaning is the situation. However, the word does not contain all the information about the situation it designates. This follows at least from the fact that the same situation can be denoted by different words. Thus, the members of the synonymous series represent the same action in different ways, highlight and emphasize different aspects and elements of the content of the situation. G.I. Kustova writes: «Let’s consider the synonymous series of get / take out / pull out (wallet from pocket). To get — emphasizes, emphasizes the distance to the object. Y.D. Apresyan defines this sign of the situation as «X is not directly within the reach of the subject’, cf. to get a book from the shelf, but not * to get it from the table (if we are not talking about a small child), from the table — to take… Overcoming this distance requires a person of some effort, from where the idea of the difficult achievability of the result arises, cf. got a deficit; I’ll get you anyway (threat); get you out of the ground. Take out — emphasizes that the object was in an enclosed space: take it out of the closet — from the shelf; take it out of the closet — * from the shelf. It also allows for enclosed space, but does not require it. Pull out — in addition to the same idea of moving from a closed space to a more open one as in take out (thanks to the prefix you-), emphasizes contact with the surface along the path of the object’s movement (due to the meaning of the root, dragging and — usually, but not always — heavy).

When you take your wallet out of your pocket, you «drag» it anyway, that is, you touch the surface, but getting it is a way of representing the situation that does not take into account this aspect of it, does not reflect, that is, there is no such sign in the verb to get, but in the situation it is. And, what is fundamentally important for us, he is known to man. If a person did not know that in the situation of «getting a wallet» there are aspects (elements, features) corresponding to the idea of «dragging», then he could not designate this situation with the verb to pull out. Therefore, the very fact of the existence of synonymy shows that a person KNOWS MORE about the situation than is «reported» in the verb… A verb in a certain sense, «choosing» only part of the information from a situation, gives a certain way of conceptualizing, understanding this situation — in other words, the verb is a semantic model of the situation, and, like any model, emphasizes something, highlights, if you like, sticks out, and darkens something, pushes it into the background the plan or even distorts it. Therefore, the other side of the coin is no less important — the remaining information that was not included in the «main», the original meaning (or in the assertive part of the meaning).