Бесплатный фрагмент - The Unknown Tsesarevitch

Reminiscences and Considerations on V. K. Filatov’s Life and Times

THE Preface

(Reminiscences and Considerations on V.K. Filatov’s Life and Times)

За Отрока — за Голубя — За Сына

За царевича младого Алексия

Помолись, церковная Россия!

Очи ангельские вытри

Вспомяни, как пал на плиты

Голубь углицкий — Дмитрий

Ласковая ты, Россия, матерь!

Ах, ужели у тебя не хватит

На него — любовной благодати?

Грех отцовский, не карай на сыне

Сохрани, крестьянская Россия

Царскосельского ягнёнка — Алексия! Marina Tsvetaeva 1

April 4, 1917

Third day of Easter

Here is the content of the verse

For the Adolescent — for the dove

For the son

For the young Tsarevich Alexei

Pray, Christian Russia!

Dry your angelic eyes

Remember the Uglich dove

Tsarevich Dimitri

Falling to the flagstones

Russia, our tender Mother!

Is it possible that you do not give?

Your loving kindness to Alexei?

Do not punish the son

For his father’s sins

Peasant Russia, save Alexei

A lamb from Tsarskoe Selo!

Once after an ordinary chat of the father and the son, I (Anzhelika Petrovna) asked Vasily Ksenofontovich about his attitude to the writing of memoirs. He answered: “I can’t stand it at all, and about my wanderings you can read in the works of A.M. Gorky. He expertly describes this time”. And to the question why he did not write, he replied: “Because all the memoirs in the world reveal the image of the author himself, and the time is not yet right, society has changed little since 1917.”

When the son volunteered to describe the life of both his father and himself, he answered: “One shouldn’t begin such a noble cause before 40 years are past.”

At that time all members of the family were in no mood either for reminiscences or for literary effort. Only now, 10 years after V.K. Filatov’s death, after numerous medical and criminal investigations and studies of archives, has each of us understood their task

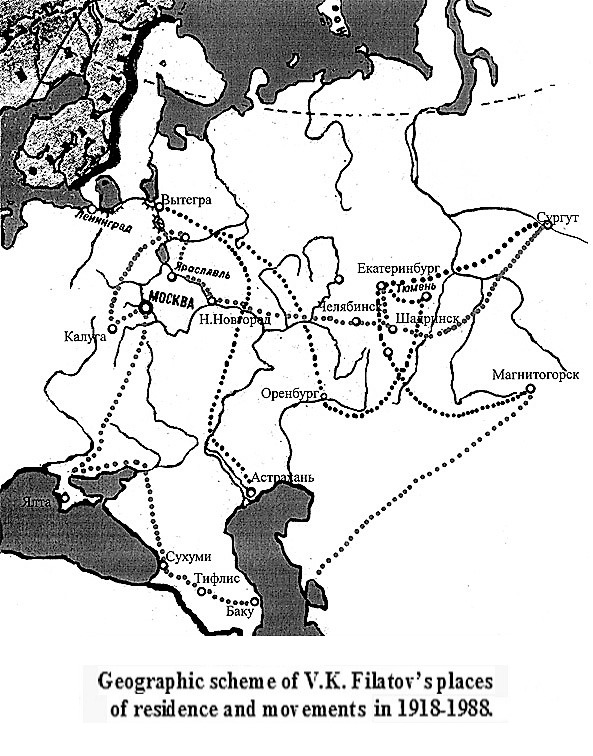

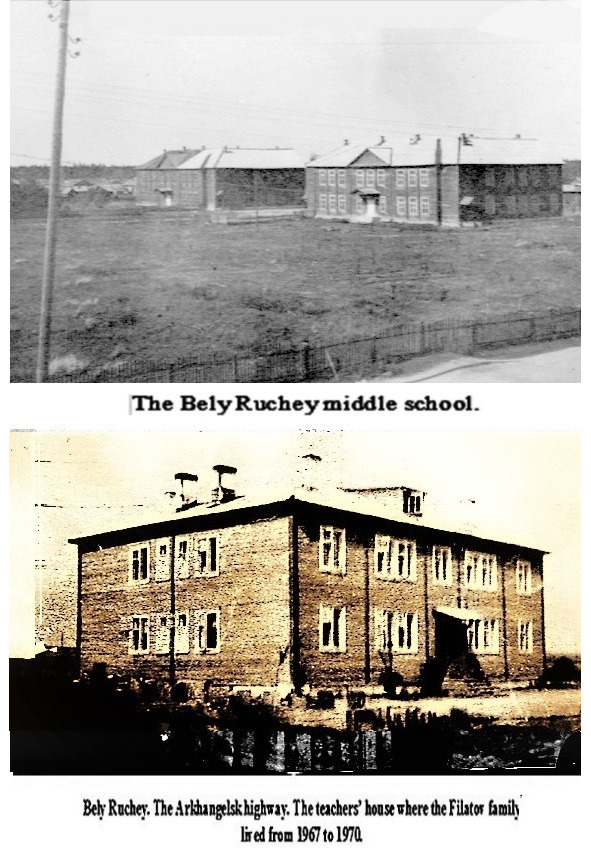

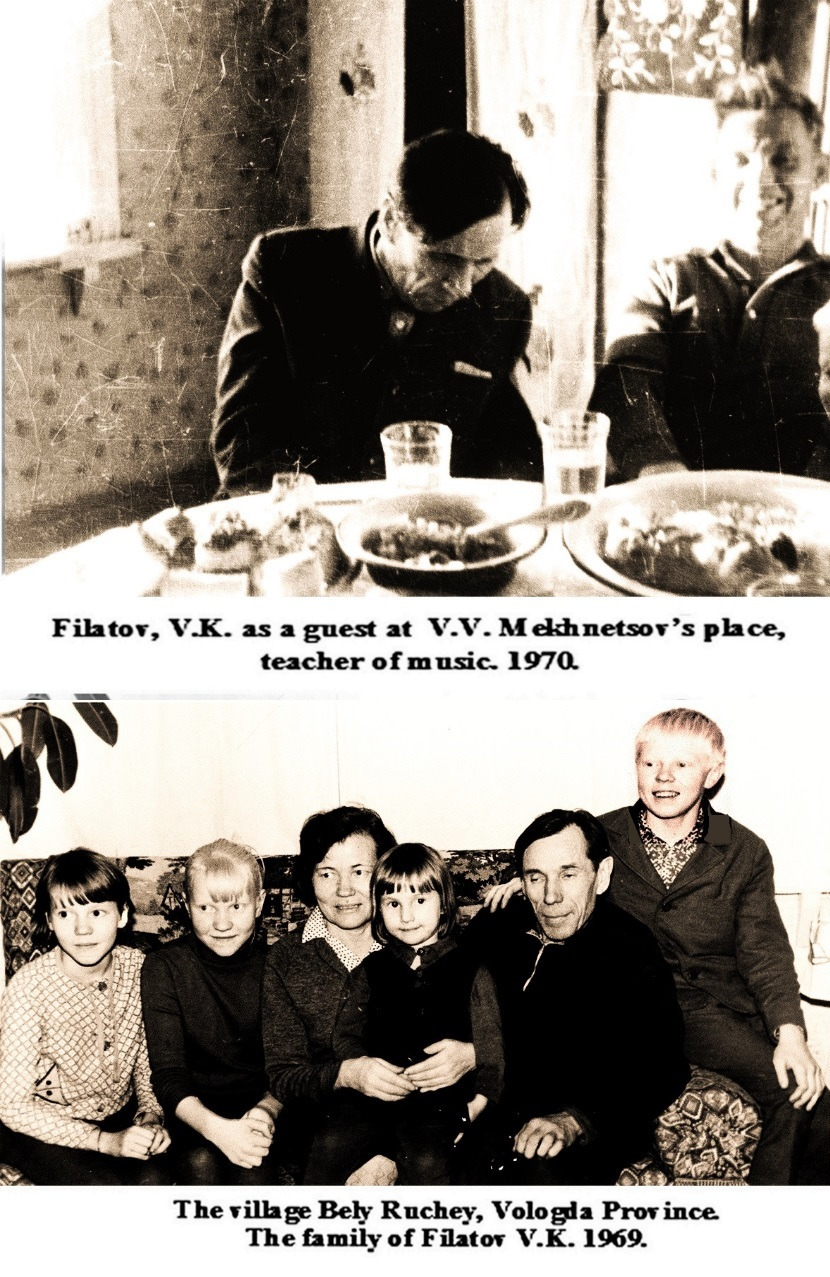

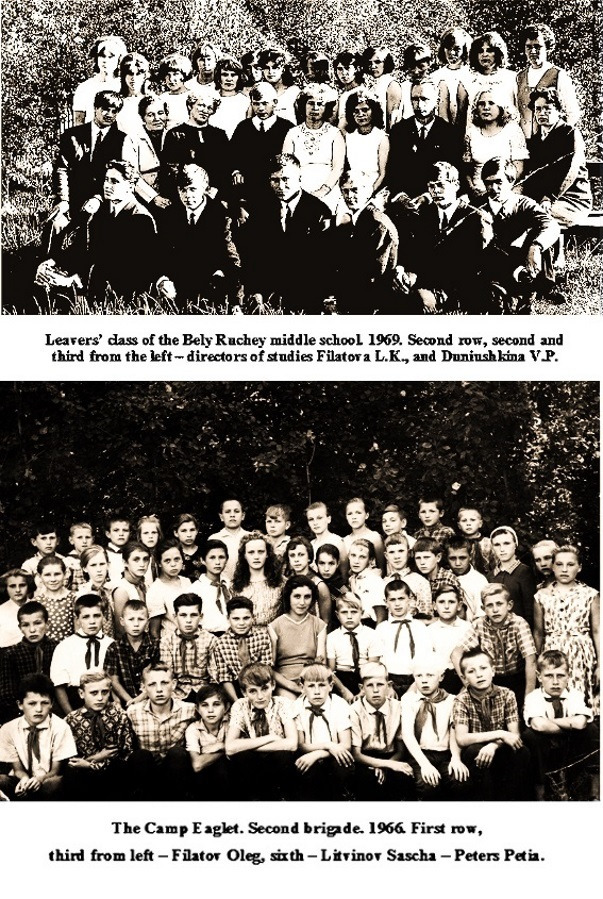

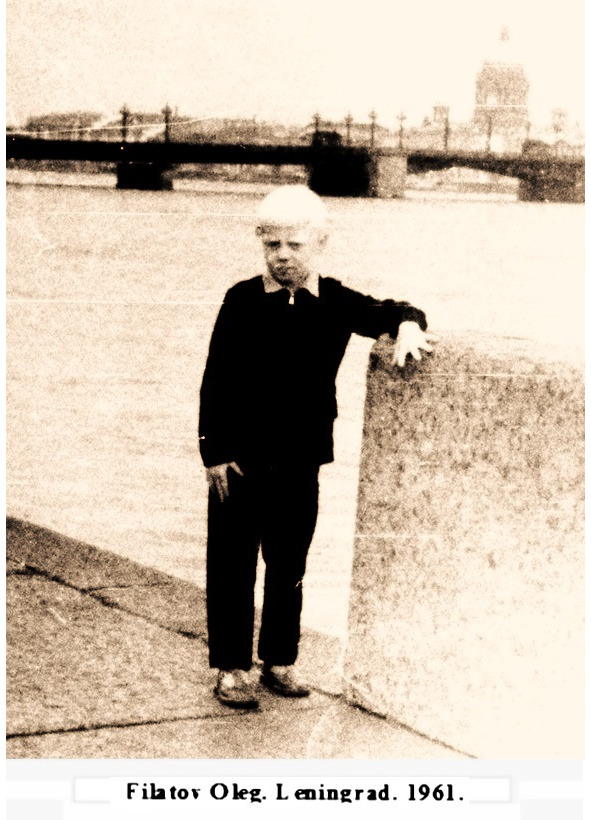

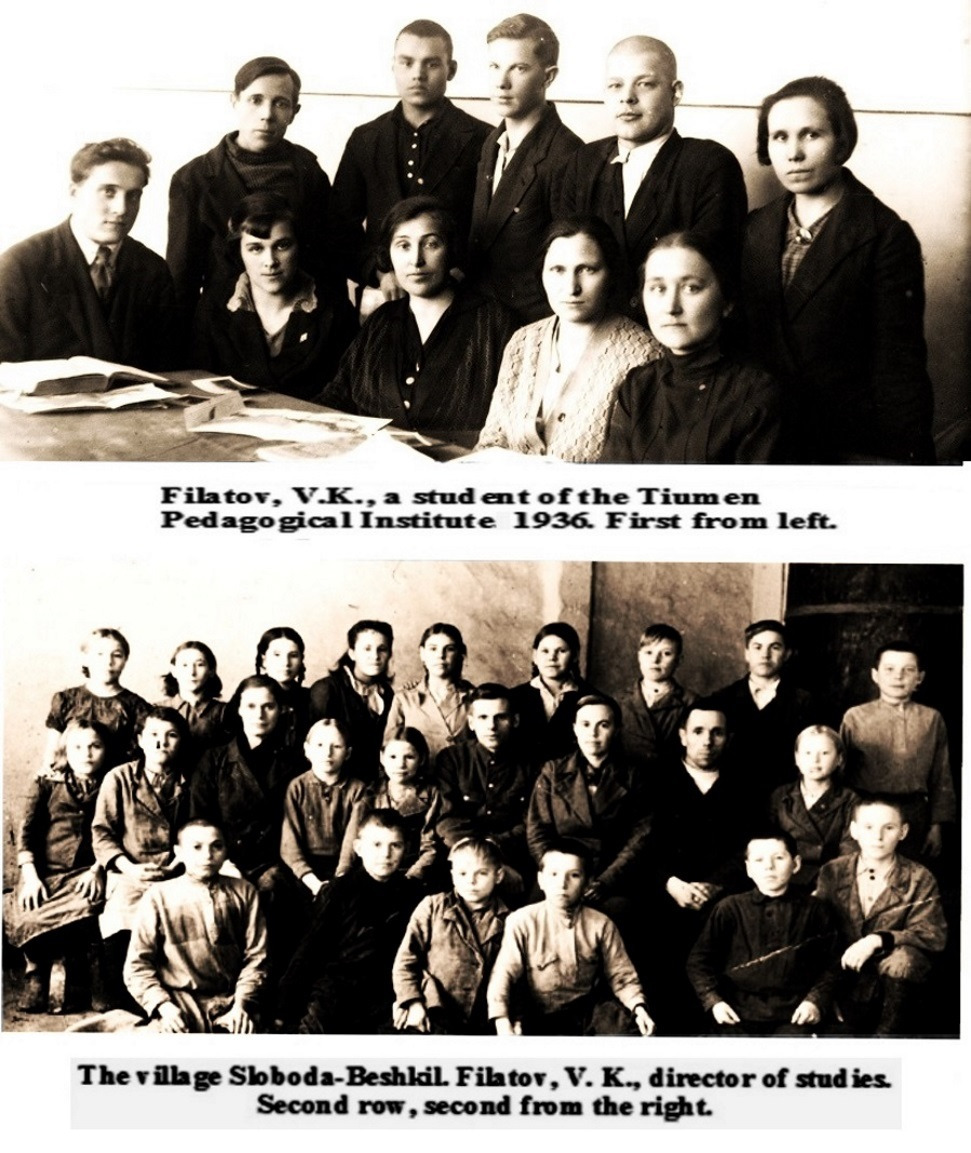

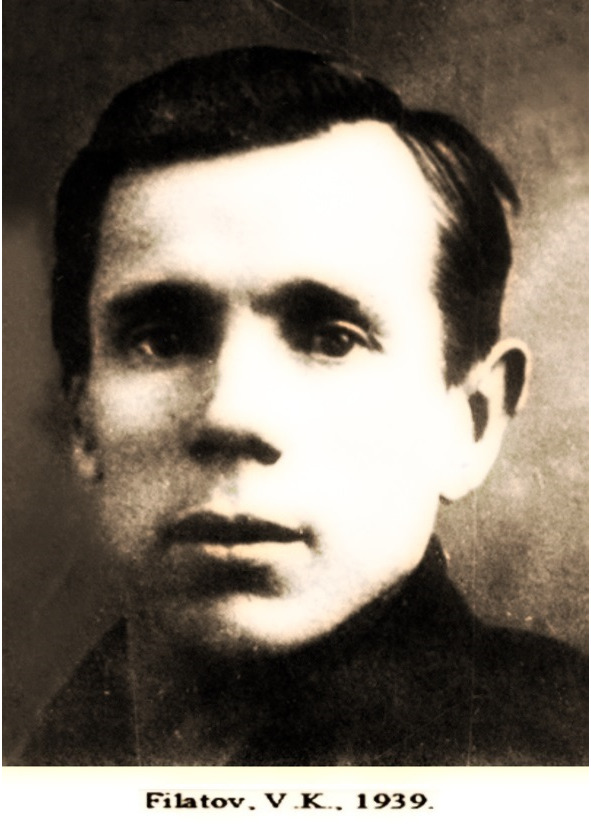

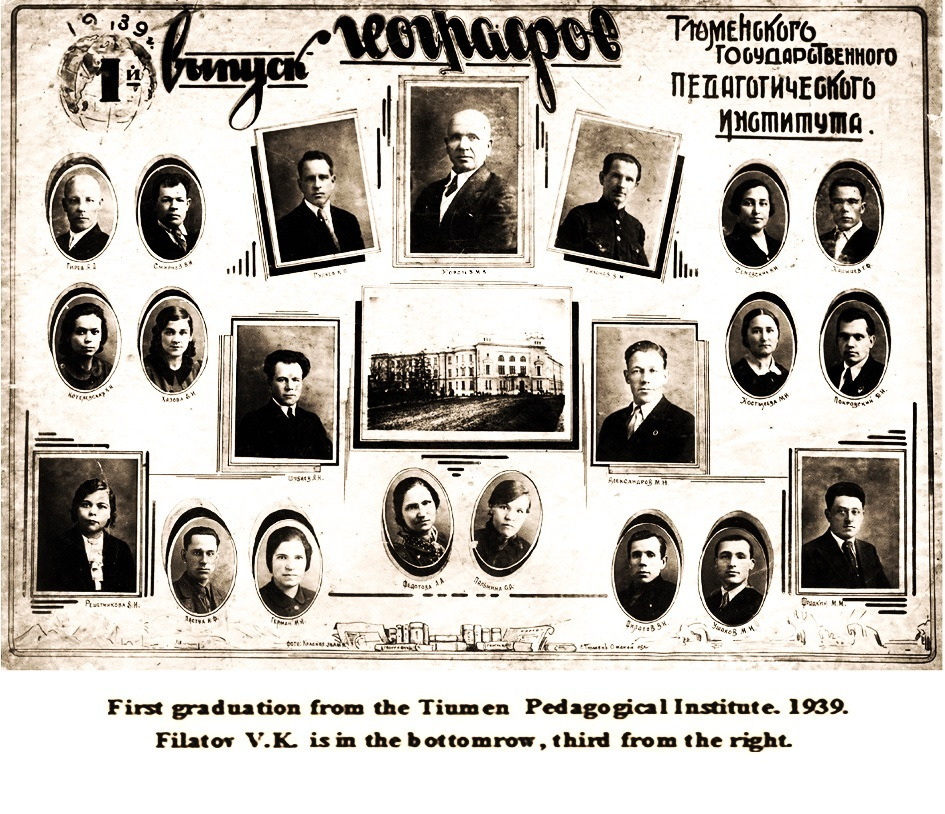

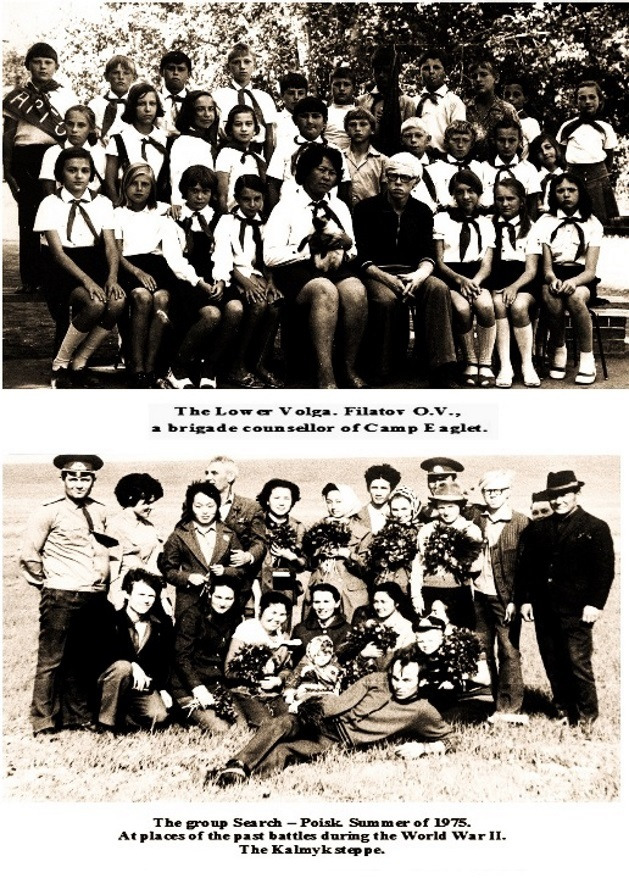

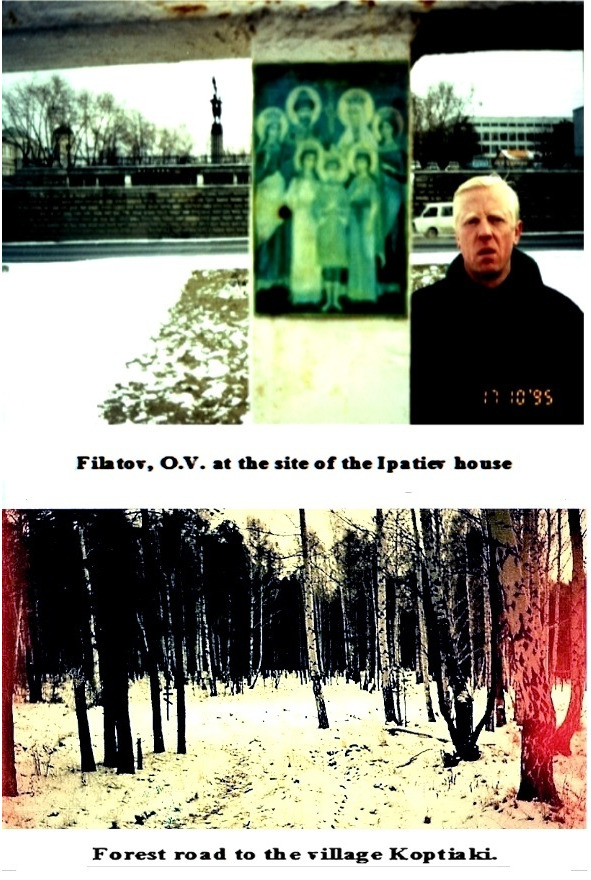

In 1998 the “Blits” Publishing House in S.-Petersburg published the book “Tsesarevich Alexei’s Rescue. The Historical-Criminalistic Reconstruction of the Execution of the Tsar’s Family”.The book describes examinations carried out on the identity of Vasily Ksenofontovich Filatov, a school teacher, and Tsesarevich Alexei. Based on the comparison of their handwriting, photos made with the use of techniques generally accepted in the domestic criminal investigation, it was established that V.K. Filatov and Tsesarevich Alexei were the same man. Accordingly, it was Tsesarevich Alexei and not V.K. Filatov, who having lived the full-blooded life of a village teacher, retired on his pension in 1967. Everything happened as Marina Tsvetaeva prayed in her poem-prayer: peasant Russia had rescued Tsesarevich. In 1953, as a geography teacher in a village school, Alexei Nikolayevich Romanov (Vasily Ksenofontovich Filatov) married Lidiya Kuzminichna Klimenkova, born in 1917, a mathematics teacher in the same school. They gave birth to four children: Oleg, Olga, Irina, Nadezhda. On starting our reminiscences we saw that some self-manifestation could not be avoided. The most difficult part of the work has fallen to Oleg’s lot. But it was he who had stimulated our desire to write and to acquaint others with our thoughts. The events of our epoch have been shown through our reminiscences about one man. The history of the soul of a highly moral and charming man, our contemporary, will be constructed, like a mosaic, of the impressions of people who have known him well — his family. I am glad that I have had occasion to have been acquainted with this interesting man, in spirit so like my grandmother Alexandra Ivanovna Karmaleyeva, born in 1898, who, like him, was inclined to original philosophic deductions and generalizations. Their discussion of life, their feelings, thoughts, their inner development will be of interest to many others. So, it was in April 1983 when I first heard the family history. I had come, at that time, to get acquainted with my husband’s parents. On March 26, I got married to Oleg and he hastened to share his happiness with his mother and father. After the feeble spring of a northern town the Astrakhan sun seemed particularly bright. Numerous fishermen in their fishing-boats were seen on the Volga. They called these springtime catches ‘the spring fishing season’. The leaves were turning green — and human hearts softened by the warmth were ready to open up to communication. On the morning of April 2 my husband and I went on the ‘Meteor’ hovercraft down the Volga to the village Ikrianoe, where his parents were living. His mother was busy with housework but his father was not feeling well after his work in the garden. Any scratches and blows would cause serious pain. ‘Doctors can’t ease my pain, — he said, — they only prescribe ‘confinement to bed’ for 2—3 days.’ He would lay in bed and read, knowing his illness too well. Why did he know it? To make it clear, we should go back several decades. But we shall speak about this in more detail later. All day on April 2nd, I spoke enthusiastically about my relatives and myself, answering their interested questions. At first the questions were general, and then they became specific and laconic. Direct questions demanded direct answers. Vasily Ksenofontovich listened to me attentively without interrupting. Then he asked if I remembered my ancestors. He was satisfied with my answer. He considered me sufficiently prepared for the story of his own. Among his kin there was a famous man — Metropolitan Filaret (Fyodor Nikitich was his worldly name). His own lands were in the region of the Middle Volga, in Kostroma Province. The peasants living on metropolitical monasterial lands as well as his relatives were nicknamed the Filatovs — this sounded more natural to the Russian ear. Filaret-Filafet-Filat — is the same name and means ‘virtue-lover’. During the Time of Troubles Filaret had been captured by the Poles, and upon returning to Russia he had become a patriarch of the church. Vasily Ksenofontovich spoke about Filaret as a man experienced in politics, which had a serious influence on the government. ‘That is where our roots come from. It must be known, — he used to say, — remember this.’ The story was very interesting and, of course, it has remained in my memory. More than once did he remind his son Oleg of Filaret, of the necessity to learn languages, to understand political affairs and know history well to avoid mistakes. Vasily Ksenofontovich wanted to know whether I had any people in my family who had been connected with the church. I told him that my great-grandfather Ivan Karmaleev, a middle-class man, had a house of his own at Tver. The house was located near the church, in a very picturesque place, where the Tvertsa River flows into the Volga. On one bank there was a convent, on the other — a monastery. All the Karmaleevs have been tied to the river. This explains their family name. In his youth Ivan had even taken a job of a barge-hauler. This had told on his health in his old age. He had got hydropsy of the joints of his legs. He could not do any active physical work, but he worked as a churchwarden and bedral. He had taught his elder son Arseny to ring the church bells. Later Arseny became the conductor of a military band and painted historical pictures. Vasily Ksenofontovich was also interested in the fate of Ivan Karmaleev’s other children as well as the life at Tver at that time. He himself said that as far back as the XIV century a bride (princess Maria) had been taken from Tver, that his family had researched the family names, or, as they are called now — their family tree. I asked if they still existed. ‘No, because of the revolution and the wars all of this research has been lost’, — he answered. Only after the death of Vasily Ksenofontovich did the family begin to compare all the stories and it became clear that Patriarch Filaret (Fyodor Nikitich Romanov, 1553—1633) had fathered the first Romanov tsar, Mikhail Fyodorovich. Vasily Ksenofontovich did not draw our special attention to this. He did say, however, that the life of Filaret and his family had not been easy. In 1601 Fyodor Nikitich was arrested by order of Boris Godunov, was forced to take monastic vows, was named Filaret and exiled to the Antoniev Siysky monastery. His wife, under the name of Marfa, was exiled to the Zaonezhye churchyard, and his under-age son Mikhail and daughter were confined in Beloozero together with their aunt Anastasiya Nikitichna. In 1606 Filaret became the Metropolitan of Rostov. In 1610 he headed the ‘Grand Embassy’ which besieged Smolensk, but was captured by King Sigizmund III together with part of the embassy. Only 9 years later did he return to his homeland and begin to help his son. Vasily Ksenofontovich ended his story with the words: ‘Yes. Such were events many years ago. And now tell me where did your grandparents come from?’ I answered that my grandmother Alexandra Ivanovna Karmaleeva was born in 1898, on April 18, and my grandfather Efrem Alexeevich Octalopov was born in 1896 at Torzhok. Ivan Karmaleev had a two-storey house at Tver on the bank of the Tvertsa, where it flows into the Volga. Ivan had ten sons and two daughters. Karmaleev was a middle-class man and had a moderate income. His daughter Alexandra was a second child in the family

Alexei Ostalopov, a merchant, had a three-storey house at Torzhok on Bolotnaya street, 5, just opposite the church. The ground floor was not lived-in. There were kitchen and laundry there. The yard was large, there was a stable. His son Efrem, born in 1896, married Alexandra Karmaleeva. Their daughter Engelina was born at Torzhok in 1928, on April 27. The family lived on the second floor. Even now, in the late century, the house has lasted perfectly. It looks rather impressive, even among the present five-storey buildings

Engelina Efremovna married to Petru Tamas, the Rumanian, born at Petroshani, Timoshoara District, Rumania. Their daughter Anzhelika was born in Leningrad in 1955, on March 30

Vasily Ksenofontovich emphasized that Torzhok had supplied the imperial family with golden embroidery. I said that my grandmother, having been a dress-designer in the clothing workshop, had learned this craft. Then he spoke about Nicholas II and the mass execution at that time. His story surprised me. He described the events in detail and spoke about the executed as if they were his relatives. First, speaking about Alexei in the third person, he imperceptibly proceeded to himself (the first person). He described in detail the rescue of the boy, gave the names of his rescuers — the Strekotin brothers and mentioned a further help from Mikhail Pavlovich Gladkikh

My husband also listened to him and asked straight: ‘So, you are Alexei, aren’t you?’

Vasily Ksenofontovich answered: ‘I’ve told you that already. You should remember things the first time!’

There were many heart-to-heart talks. Quietly, without hastening to tell everything at once, but little by little preparing for us our own conclusions, he achieved the main thing — he taught us to think. The ways of God are unknown

Being a tourist in Bulgaria, I had an opportunity not only to see the sights of the country and to get acquainted with the culture of the people but also to be blessed by Metropolitan of Plovdiv. Here is the story of it. It was July, 1982. I walked about old Plovdiv, taking photos of the architecture of the epoch of the Bulgarian Renaissance, gathering interesting details. Going down the hill by the marble staircase I saw the Christian church — an ancient house buried in flowers and rose bushes. A stone wall was in place around it and two men were standing by the forged gate. I photographed that picturesque corner. The men stopped me. They asked if I knew what house was behind the wall and invited me to see it. It was very interesting to me, but I hesitated to go there alone. By chance I got my opportunity. Three tourists from our group happened to be nearby. During an excited conversation in different languages we learned that the men were monks from the staff of the metropolitan chambers. They spoke lively in Bulgarian and we told about ourselves in Russian. They repeated their invitation and we agreed. The Metropolitan’s residence included several small halls for business talks and a large conference-hall decorated with carved oak panelling. There were portraits of the Head of the Church and of the Head of State on the walls as well as portraits of the Metropolitans of Plovdiv. We were also shown the private chambers, the cell icons and a prayer-book with a silver cover. By the end of the visit we unexpectedly met the host himself. He and his retinue had just returned from Greece. It was a business trip concerning the problems of the church. He was also accompanied by secular officials who had conducted negotiations and shot a film on Orthodoxy

We turned out to be the center of attention. I told them where we were from and about the sacred places of my city: the chapel of the blessed Kseniya of Petersburg. I decided to ask for a blessing by the Metropolitan of Plovdiv. The sovereign blessed me with the words: ‘I bless you, a God’s slave, to great deeds.’ We were invited to take part in the evening liturgy and we agreed with gratitude

So a chain of many opportunities had started

On the following day our tourist group set off for Kazanlyk and Shipka. There, at the height of 31m above sea level, stands the Russian church of Saint George built in honour of the Russian soldiers killed in action for Shipka. While the other tourists were being photographed and fussed over by the guide, I went to the cemetery near the church. A woman came up to me and told me about the graves in front of which I was standing. According to legend, the people buried there, were from the Romanov family which had ruled Russia for more than 300 years. Our country is going though peculiar times. Old Russia has gone but still there is nothing new, though more than 80 years have passed since the October upheaval. Life had made Vasily Ksenofontovich roam the country but everywhere he went, this cultivated man was received willingly. He found work everywhere but he felt drawn to Saint-Petersburg. He had sent his grown-up children to their native country, to their native city. My grandparents had also been sent to Povolzhye, to Tatarstan, to establish the Soviet power there and organize agriculture. They accepted the good local traditions and customs and helped the Tatars, but they could not consider themselves one with the people. The village which was composed of mixed nomads could not be called a collective. It was very difficult to cope with everything. An attempt had even been made on my grandmother’s life, but the people had shielded her with their bodies. Therefore when the term ended, Efrem and Alexandra, like many others who had left their homelands for different reasons, tried to come back. They lived in Moscow for some time and before long they were sent to Leningrad. My grandfather headed the building organization and my grandmother was the head of the Vasileostrovsky Party Committee. Grandfather had the right to carry a weapon. He did not wear a uniform but he lived as a military man. He went to the front from the very beginning of the war

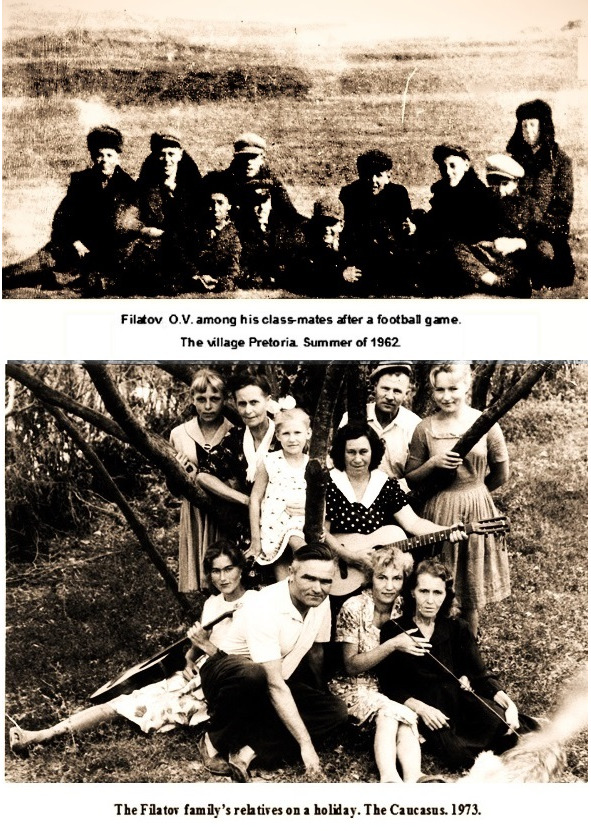

I told about my relatives and Vasily Ksenofontovich told about his life in the Orenburg district, in the German-Dutch settlement

He said that it was both possible and necessary to learn from the Pretoriya villagers. While each member of the collective farm had a household of his own, life itself made them strengthen the feeling of collectivism. They would support an individual but only of their nationality: they neither recognized the foreigners nor helped them. In other, outwardly successful collective farms, in fact, an attitude of indifference was growing, that is, a man understood an interaction between ‘my’ and ‘common’, but nobody was interested in his opinion (probably there was no need). Ultimately, he got convinced that he cannot change anything. He knew, saw, understood but did not influence anyone or anything. Vasily Ksenofontovich would say: ‘Our freedom and independence are not supported financially. An enormous mass of peasants and workers have been reduced to the state of poor proletariat. The government is very strong, it has all the means of production, and any abuse of power tells immediately upon a multitude of people.’ And now, in the late 90’s we witness a re-organization of political power but the country has not been prepared economically. The government does not conside it’s obligation to care for the needs of individuals. All of us have been office workers and had no means of production. Now the right of the collective use of already accumulated resources, that is the results of collective work, has been cancelled. But the government has not properly determined the economical rights of an individual (that is, the right of property). Vasily Ksenofontovich said: ‘The Russian State and the Russian soul now suffer a chronic disease because of the political machinations. Our ancestors, who had modernized their lands to bequeath them to us, have left us quite other lands.’ I still remember our talks. Of course, we talked not only on the social-political themes. Vasily Ksenofontovich spoke about his life and his children. Oleg was their first son, then two children, three, four… What should bringing up children start with? Daughters are most brought up by their mother. And he, father, teaches his son to nail a plank, to saw wood, to cut a stake, to dig a vegetable bed, to sharpen an instrument… He teaches his son not only with words but he finds real work for him. The aim of Vasily Ksenofontovich had been simple and clear — to LIVE. I listened attentively to his analysis of the experience of life of other people and a critical comparison of it with that of his own. The past… the experience of previous generations… Life of fathers and mothers, grandfathers and grandmothers… Why do we often mentally look backwards? What do we search for in life that has already passed? Probably, they had also looked back into the depths of people’s lives. And so on generation after generation. Now it is our turn to record, understand, and preserve everything that has been accumulated by concrete people. The life of Vasily Ksenofontovich had its specific history, unique details, and he told them to each member of the family in a different way. Each of his stories revealed a new turning point in his life, every time new facts appeared. Each story was not an exact repetition of the previous one but revealed some regularity. Details added an exactness and volume to the events

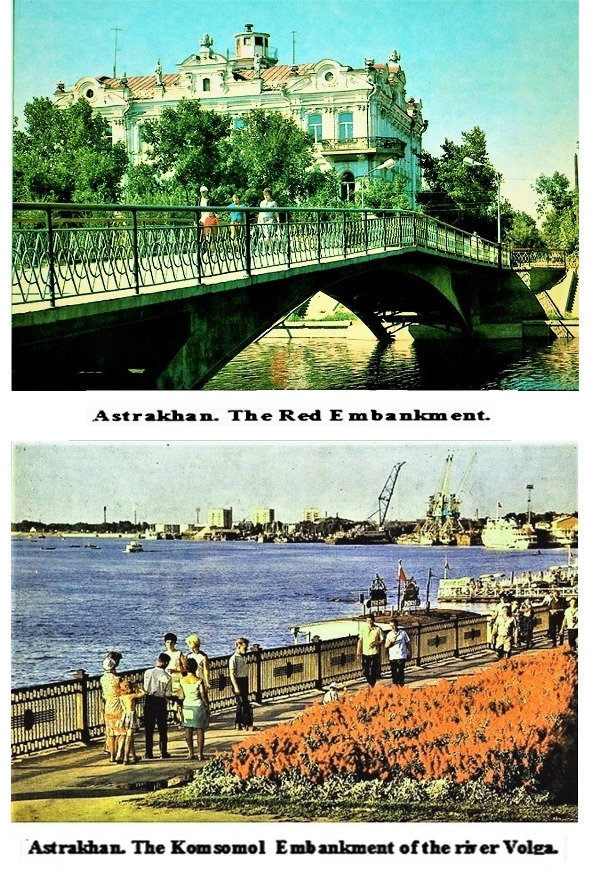

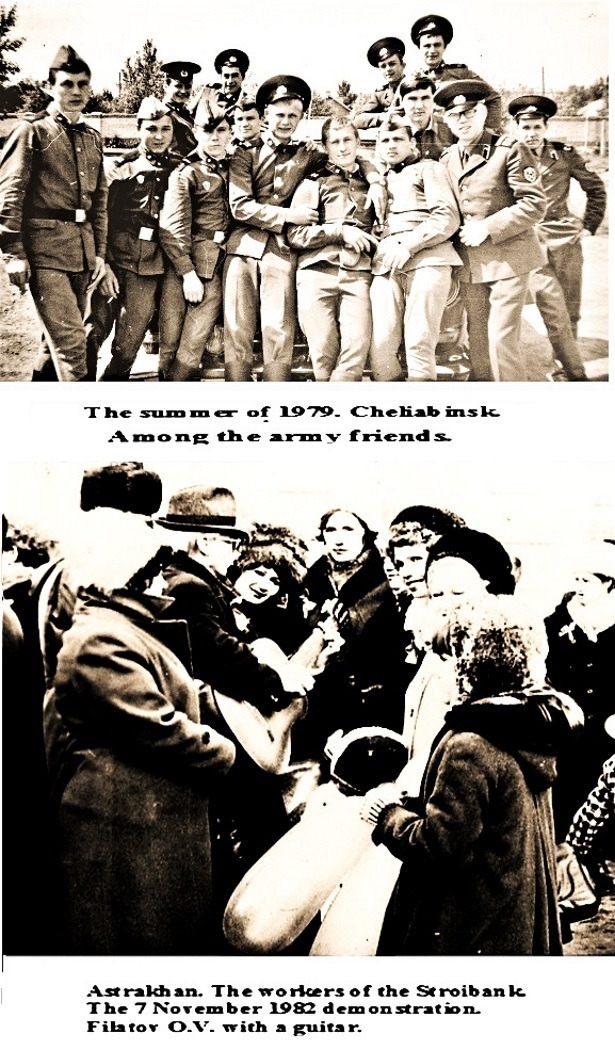

In September of 1984 my mother Engelina Efremovna went to the village, Ikrianoe, to see her relatives. There she heard for the first time that after the execution of the Tsar’s family the boy remained alive and that that boy was, he, himself. He had survived this tragedy as a youth, and during many years he had been keeping, the burning truth about his experiences to himself. Mother was surprized considering this outwardly plain man: what could be the source of his strength, his endurance and his emotional energy? Mother and Vasily Ksenovontovoch talked much about the war. She was 13 years old when the war began. The German troops besieged Leningrad and the hospitals started being organized there. My grandmother worked in the Institute of Obstetrics and Gynaecology. During the war it was re-organized as a hospital specializing in cranial-brain and jaw surgery. At first Mother worked there as a junior nurse, then as a telephone-operator, and then she was taughed to be a surgeon’s assistant. She accompanied ambulances, took the wounded away from the battle-fields and delivered them to the hospital. Mother told us how they had nursed the wounded through their illnesses and how they almost died of dystrophy. My grandmother was the commissar of the hospital and could have a ration but never took it. Vasily Ksenofontovich recounted how he had met thousands of refugees from Leningrad and had accomodated the evacuated people. They were very weak but their stories inspired others with faith in victory. Lidiya Kuzminichna also told about her military past. Because of frequent moves? It was never officially registered, that she was a medical sister during the war. With Oleg’s help, we registered her. They listened to us in the recruiting office and sent an inquiry to the archives — justice triumphed. Mother helped examine the documents, write an application and accompanied Lidiya Kuzminichna to the commissar. Some years later Oleg appealed to the military-medical archive where additional documents were found, and Lidiya Kuzminichna received an additional pension. But it was only in 1997! The elder generation has something to remember. Their life has been full of trials but they have not become pessimists. On the contrary, they rejoice over life. Mother and Lidiya Kuzminichna performed their household duties, but also walked through Astrakhan looking at the ancient houses and the Astrakhan Kremlin. Some days later Oleg and I also went to Astrakhan, where the two grannies (Lida and Gelia) nursed their granddaughter Nasten’ka. She was 8 months old then. Oleg spoke about the history of that region. We walked a lot and visited friends. Grandad was also fond of looking after his granddaughter. He took her in his arms but she would not sit a minute. She would jump to her feet and skip on his knees. His hands were massive, T therefore it seemed that the child had no body and only her legs and head were skipping. If the child was out of sorts for some reason, her grandad sang songs or ditties and clapped his hands. Sometimes he played the piano together with Nastia. It was something unimaginable. Nastia liked it very much. Later, granny Lida helped this tiny little child play the piano by herself. I took their photo

Each day I bathed my daugher in a baby’s bath, dipping her, splashing the water. The leaves of the cherry tree rustled above us. In the garden, Grandad sat and loughed, watching the bathing

His night’s lodging was in the garden, in the bed with a canopy. Usually the nights in the open air were quiet, but sometimes the dust storms made him go into the house. In the evening we used to have tea and talk. Life passed quietly and peacefully, until one day a thief sneaked in to the garden and then into the house. Everybody was frightened. Vasily Ksenofontovich calmed us down with the words: ‘Nothing can be more frightful than the basement of the Ipatiev house. They shot the people there, but a thief comes by chance.’

He took an axe and went to the garden to sleep. But we could not go to bed and sat a long time, discussing the incident

The appearance of Vasily Ksenofontovich was noteworthy and my lack of patience was well known to the artists who saw a model worth painting. He had impressive eyes, shadowed by bushy eyebrows which struck me with their wisdom as if they had absorbed the life of the age and its pain. His parchment-skin face was lean

Every time I tried to sketch him, he became shy and went away to the garden. He also did not like to be photographed. He would sit in the shadow and the photos were indistinct. Once we (Oleg, Vasily Ksenofontovich and I) were mending the roof, covering it with a new roofing-felt. When our work was nearing completion, I managed to take his photo, because being lame he could not rapidly descend from the ladder. Feeling confused he smiled and went on repeating: ‘Now, now!’

I did not draw pictures of only Vasily Ksenofontovich. I would go to the Volga, look at the thick, branchy trees growing along the river and at villages resembling clusters of mushrooms. They seemed something ancient. (Water, the river bank, a burning buoy). As soon as you wanted to put them on paper, you understood how difficult and mysterious it is and yet at the same time, surprisingly simple

Oleg asked father to go fishing but Vasily Ksenofontovich refused saying: ‘I can’t keep pace with you. I only walk about the garden.’ Next morning Oleg gathered the fishing-rods, got worms ready, took bread to coax the fish up, got instructions from his father and, together with his sister Irina and I, set off to fish. The morning was foggy but the sun rose higher and higher, and the scenery changed, becoming more cheerful. Without wasting time I began sketching a small fishing-boat, peacefully lying in the blue-gray mist on the unruffled surface of the water

The fishing was successful, my husband caught several perches and red-eyes, but his father made fun of his catch. Then Oleg made arrangements with his friends and we made a motor-boat trip to a fishing-boat. There we bought a big zherekh. These fish, like zander, wild carp, bream, and catfish, spend the winter in pits and are called pit-fish. We spent the evening at the river-side cooking fresh-fish soup on a fire, in a large cauldron. We also bought several kilograms of bream and, for the first time in my life, I salted and dried fish. Later, in the winter, we treated our relatives and friends to our stock of fish

The house stood on a Red Mound surrounded by a multitude of ilmens (semi-flowing reservoirs) overgrown with reed and kultuks (bays). 150m from the house, the erik (a deep sound from the river to the lake) Khurdun flowed which supplied the villagers with pumped water, to water their gardens and for household needs. Every morning Lidiya Kuzminichna first watered her garden and only then did she fry scones and called everybody to take tea. In the evening she was busy with sewing and embroidery. She sewed clothes for her daughters, granddaughters and neighbours. Everybody loved her creations

Vasily Ksenofontovich used to say: ‘The traditional Russian culture must be preserved. The Slavic people love a loose cut of clothes. Heavy boyar clothes were the result of the Tatars’ influence on the Slavonic traditions. Peter the Great was convinced of it.” Vasily Ksenofontovich recalled also Alexander III: “In the late XIX century the army was dressed in a uniform of the Russian cut. The tsar himself wore a new Russian tunic. The Russian army had a comfortable and practical uniform.” In their childhood the girls dressed up in embroidered blouses and Oleg — in a red Russian shirt with a sash. Our holiday came to the end. Later, in Leningrad, while recollecting it, we wrote letters to Astrakhan and received news of those we left behind

“Anzhelika and Engelina Efremovna, we congratulate you on the festival and wish you health, happiness in everything and high spirits

Spring has arrived. The buds are swelling on the trees. We are digging our gardens. Radish, which I planted in January, will grow soon. In April I will plant out strawberries. In my room there are already seedlings of pepper, and tomatoes. The tomatoes have started blooming. The cucumbers have sprouted. Please, write and tell us how things are with you. The apricots will ripen from the 15th to 20th of July. It would be better if Oleg went on holiday in the fall. My love to Nasten’ka

Anzhela, send me your measurements

I kiss everybody. Your mother.”

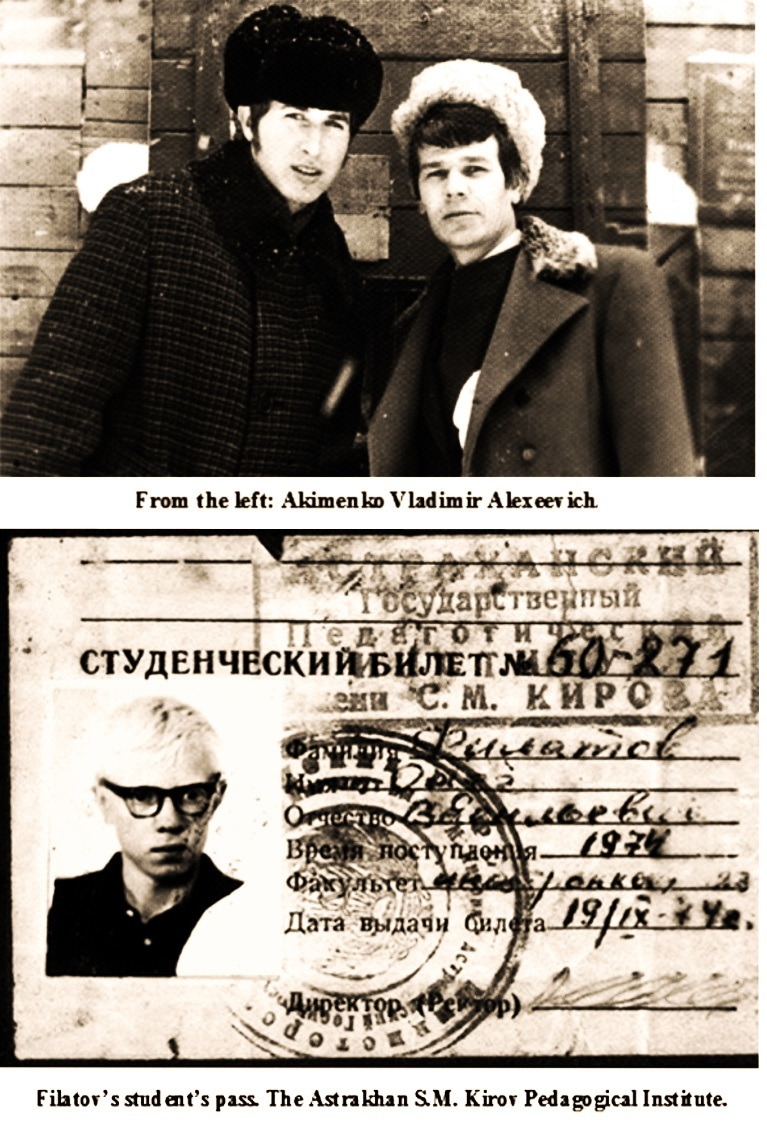

The next time we went to Ikrianoe, it was in May of 1985. There was much work in the garden. Akimenko, a friend of my husband, gave us his car and we went to buy a wire mesh for a fence. Every year we spoke about substituting the reed fence with wire mesh. So, at last, the wire mesh was bought and the work began. We put in new wooden posts, made a new wicket-gate, mowed the grass in the garden, and put up the new fencing. The garden became more spacious. We graveled the walks and put down concrete. The garden was indeed changed. After work we would go to bathe in the river. We would buy fruit and other products and, in the evening, when the heat abated, we would eat supper with pleasure. One day, they brought the firewood for winter. Only Vasily Ksenofontovich and I were at home. And we had to unload the truck and then to roll the big blocks in to the garden. Vasily Ksenofontovich limped, and groaned but worked quickly

In 1987 we came to granny and grandad with two granddaughters — Nastia and Yaroslavna. Anton (Ira’s son), was also there. The 3 grandchildren played merrily in the garden, amusing the grown-ups

Vasily Ksenofontovich was ill, he would lie on his small plank-bed for hours. I recalled how the people cured themselves in the salt caverns on Lake Seliger. During the war there was a hospital there. Many people were cured in these caverns. My grandmother had told me about it. Vasily Ksenofontovich recollected his youth and said that he had also been there. Oleg and I went to Astrakhan to search for some necessary medicines. In spite of being seriously ill, Vasily Ksenofontovich was always an optimist. Constant sufferings during his youth had not broken him. Throughout his life he had had faith in a great and a strong Russia. He would say: “She will return to her centuries-old traditions. People will learn not to destroy but to create.” Vasily Ksenofontovich, within his powers as a teacher, tried to influence all young minds and introduce them to the richest cultural and historical traditions. He taught this to everybody: pupils, his children, and his grandchildren. Naturally, special attention was paid to his son. He cultivated generosity and dignity in him. During the upbringing of his family he gave to his son the professional knowledge and skills required to govern the State. This book as presented to the reader consists of several parts. Oleg Filatov’s reminiscences make up the main part of the book. This is normal. Owing to the special history of Russia and the life of Tsesarevich’s family in the period of the Soviet power, under which name he may have lived, what he may have been, he could only have passed this experience on to his son. Apart from a description of the way of life, the book contains also a review of press, reports, archived materials, assessments of forensic medical men and lawyers. The position of the General Prosecutor’s Department of Russia is given, which rejects the results of the examinations made, without denying, however, the effectiveness of the applied techniques in all cases. Such a position of the General Prosecutor’s Department may be reasonable and understood only in one single case: to acknowledge the identity of V.K. Filatov and Tsesarevich Alexei, the results of examinations made by qualified criminalists on their initiative, making use of techniques effective in all other cases, are quite enough for the Prosecutor-General. But if the identity of V.K. Filatov and A.N. Romanov when examined by methods of genetics is confirmed, it will make the results of the examinations carried out before incontrovertible. And this does not coincide with the political order executed by the officials of the prosecutor’s office, since it utterly changes a lot of monarchical scenarios: then would appear one more monarchical scenario, most unsuitable for the ruling “élite’

Having read this book, the reader will hopefully ponder over his life, the life of his generation and of the previous ones. We hope for it. Anzhelika Petrovna.

CHapter I

SOURCE

Мысли у дома Ипатьева

Дорога длинная, пустая была так долго без огня

И вот пришла пора святая, которая спасла меня

Отцы и деды, поколенья восстали мигом

Рядом в ряд

И мы, как воины России, должны спасти её опять

Благая вера, где ты в людях?

Восстань, воспрянь и воскреси

В Россию веру вековую в народе нашем укрепи

Заветы предков поминая

Нельзя России изменять

О Русь!

Воскресни, созидая

Чтоб, созидая, побеждать

Oleg Filatov

October 1995

Thoughts near the Ipatiev House

A long road has long been dark

But one day the Holy Dawn has saved me. Fathers, grandfather, generations

Have risen, row upon row

We, the Warriors of Russia

Must save our land once more

Oh, good Faith, where are you?

Help the Russian people rise, liven up, resurrect

Remembering the behests of ancestors

One cannot betray one’s motherland

Oh, Russia! Resurrect and create

Through creation you will win the whole world

Когда приходит час судьбы

Когда приходит час судьбы

Мы поминаем всех усопших

И на останках тишины

Мы мысkи наши поверяем

Мы помним всё, всё, кроме снов, — История, судьба, Россия

Когда приходит час судьбы

Мы поминаем всех героев

И день и ночь, и тьма и свет

Борьба, смятение души

И горе, счастье и любовь

Нас посещают в час единый

Приходят новые огни — Огни, которых ожидали

Мы все, конечно, сплетены

И нашем горем, и печалью

Судьба и Бог, и мы — России верные сыны

Сегодня путь мы выбираем

Oleg Filatov

September 1994

When the fatal hour strikes

When the fatal hour strikes

We commemorate our dead

And in the silence the thoughts

Are crowding into our minds

We remember everything but dreams — The history, the fate, Russia

When the fatal hour strikes

We recall all our heroes

And in day light and at night

The fight, confusion, grief, happiness

And love visit us at this hour

New lights we were waiting for

Have come

Of course, we are all interlaced

With our grief and sorrow

Today the Fate and God, and we — The faithful sons of Russia — Are choosing our way

I often thought about how I coucld tell the truth about my father. After having talked with my friends, colleagues, and acquaintances I came to the conclusion that it should be written in the way he himself had told about it. He was not a historical character of a distant epoch but our contemporary born early in the XXth century and during 84 years, together with his people, endured hunger, suffering, and repressions. It is almost impossible to imagine, how he felt, realising who he was and keeping silent for so many years. He had seen and endured a lot to save himself and his family, his children. Maybe we shall never know the whole truth but we should try. “Non progredi — estra gredi’ (“Not to go forward means to go backwards’)

Father had lived a long life. He had compensated for his physical defects by his constant desire for harmonious development and knowledge. This had given him a stimulus to live. We, his children, were born when he was far from being young, we cheered up, he sensed a new meaning in life. And when his granddaughters were born, the truth finally came out and he told their mother, my wife Anzhelika Petrovna, about his tragic fate. It was in 1983, five years before his death. Only then did we understand that Father and the boy whom he spoke of as executed on the night of 16—17 July, 1918, but not killed, in the basement of the Ipatiev house in Ekaterinburg, — was the same man, that is, he was Alexei Nikolaevich Romanov. Before, he had told us about it allegorically, piece by piece to each of us. Now we are collecting all his stories and our reminiscences of him to better understand what had happened. Part of the reminiscences of the members of our family — his children and his wife Lidiya Kuzminichna (due to her, strictly speaking, he had lived for so many years) — has been published in newspaper articles and served the basis for special investigations carried out by experts and continued until now. Unfortunately, there are many gaps in these reminiscences: he was restrained in his stories and we were children then and did not ask him any questions, we simply believed that what he had said was true. How could we not believe in our father, when we saw how he suffered and understood that his life could have been quite different! One might notice repetitions in this book, but this is not so awful. The most important thing is — to be honest (this is the basic principle) and to tell the truth as it could have been/. Of course, much could have been taken from the archives, both open and closed. But we cannot get there due to some circumstances, partly for lack of money, partly because of the fear which still lives in people. But without reading these pages, which will cause us to not allow anything like that to happen again, we will not know how the history of our country could have formed, without the revolution. If we speak about repentance, we should understand who killed Emperor Nikolas II. Why have none of the leaders of the country, specialists in forensic medicine, or laywers suggested a true version of those events in July 1918? How has the life of the participants of this tragedy in Ekaterinburg developed?

In 1988, on his death-bed, Father said: “I’ve told you the truth, and that’s what the Bolsheviks have brought Russia to.” We, his children, know that he has not deceived us. Unfortunately, he had told us little, and we still have questions. But as if his soul is still with us, we ask him questions, as if he was alive, trying to go back in time and associating with him

When one’s parents are alive, one takes them for granted, without thinking that they are not going to be with us forever. Therefore we have now to collect the crumbs of what he had said, supplementing his story with our own considerations and new facts revealed during recent times. Therefore Father’s story is sometimes interrupted by my reasoning’s. The investigation is not finished yet. Our friends, relatives, colleagues, and scientists interested in this story are helping us to carry this heavy cross that has fallen to our lot. I hope that, after all, all of us will know the truth. And this will be the real compensation

Yes, this is a fantastic and still not cleared up story. The first reaction to it of most of people is: “It can’t be so!” When children are confronted with something unknown, they cry, but grown-ups try to turn their back on it and ignore it. Apparently this is the reason, why, despite some serious examinations carried out on our initiative and voluminous, actual material now accumulated by various scientists, the official structures have not seriously investigated this story, which has a lot of blanks. There is no other explanation to the contrary. But nobody has been interested in checking up on whether it is so. And maybe the point is that such a story does not appeal to everyone… This is a form of unconsciousness, one way to forget. I am a christian and it is my opinion that only atheists have to be convinced. Of course, we, his wife and his children, simply believe in our father, but still not everything in his life is clear to us, because he had to keep out of sight in order not to expose us and the people who had helped him to danger. Therefore we are trying to find more facts to unravel the whole truth about this martyr who lived a long life, and saw and experienced so much that it would have been enough for several lives. As far as the improbability of this story is concerned, — the rescue of innocentchildren from terrible death is a miracle. God saves!

Father’s Biography

How did this all start? It began when father himself prompted us to start studying his life. He did it with his stories, when he told us what he knew about the execution of the Tsar’s family. Of particular importance for us was the fact that a boy remained alive after the execution of the Tsar’s family in Ekaterinburg, and in 1983 father gave us detailed information that the boy, i.e. Tsesarevich, was he himself. This information corresponded to the facts reported by members of the State commission to the media. Later on the family decided to be more active. Within the framework of a criminal case, prosecuted on the fact of murder, without trial or inquiry of the family of Nikolas II, it is said that the bodies of two of the Emperor’s children — Tsesarevich Alexei and his sister Maria — have not been found

We have gotten acquainted with the inquiry carried out by the investigator Nikolai Alekseevich Sokolov1. We have studied the materials of his book. We have gotten acquainted with the evidence of Vladimir Nikolaevich Derevenko, the Heir’s doctor, with the materials of interrogations of staff-captain Simonov, later a member of Kolchakov’s counter-intelligence, as well as of investigators: I.A. Sergeev, V.F. Kirsta, and A. Nametkin. We have read the report by the public prosecutor of the Kazan forensic department Miroliubov to Minister of Justice Strynkevich on the course of inquiry into the execution of Nikolas II and his family on December 12, 1918. Tomashevsky, investigator, said that many of those mentioned above were of the opinion that not everybody had been killed on the night of July 16—17, 1918. Staff Captain Simonov’s opinion deserves special attention. The fact is that before the White Czecks occupied Ekaterinburg, Simonov had served on the third army staff under the command of Berzin. General Diterichs2 mentioned in his book that he had sent the officer to the army of Kolchak. After the occupation of the town he served under Admiral Kolchak as chief of the intelligence and counter-intelligence unit. He himself reported to Admiral Kolchak that, according to the information available, the Tsar’s children had been rescued. However later on General Diterichs dropped this theme (that is, the content of the report by Staff Captain Simonov)

We should emphasize that the life and fate of the participants of the outside guard of Ipatiev house have not been mentioned in any of the published materials on the investigations of the execution of the Romanovs. We may only get detailed information on the team of executioners. And who were the soldiers from the local people, the participants of the outside guard? Who were their relatives? Where did they live? What was their occupation? What were their connections? By that time the situation had been unstable, the Soviet power had not yet been established in the Urals. The people had lived as they always had

What was to be done if the power changed to-morrow? What would life have had in store for them if the Whites came? In those days, being in contact with the Tsar’s family, could change their opinion of them and help them to regain power. They did not know how long they would guard the Ipatiev house, or what was in store for them. They exposed themselves to risk. The Whites and the tsar’s adherents could find them and they would have to answer for their service under Soviet power

One should note that the investigators have not examined the fates of those children of Nikolas II who had been executed but not killed, let alone who could have rescued them provided they remained alive, that is, Tsesarevich Alexei and Maria, Grand Duchess.From Father’s stories we, his children, knew that the rescuers were the Strekotin brothers, Alexander and Andrei, and the Filatovs, Alexander and Andrei, from the first company of the First Peasant Regiment, quartered in Ekaterinburg, as well as Vasily Nikanorovich Filatov, brother of Afanasy Nikanorovich Filatov who fathered Ksenofont Afanasyevich Filatov. Vasily Nikanorovich had lived in Ekaterinburg till 1921 and after serving in the army he returned to Shadrinsk.The respective archives of the CPSU Central Committee do not contain any information about the Strekotin brothers. There is information on the jewels in corsets handed by Yurovsky, but nothig is said about two other corsets, those of Tsesarevich Alexei and Maria Nikolaevna, Grand Duchess. Yurovsky was responsible for the delivery of the royal valuables. What did he do with these corsets? How could he allow for such a shortage? Maybe he got them as a payment for the freedom of the Tsar’s two children? Answers may be found in his biography. We should take an interest in the qualities of this man, hisstrengths and weaknesses, his vital interests. After all, he was born long before the revolution. We learned that from youth Yurovsky had loved to search for hidden treasures. He did it and was rich. From 1905 he had lived in Berlin. His biographical data can be found in a book by O.A. Platonov1.Hardly anybody noticed the fact that he had lived in Berlin, that he had changed his religion (and this always implies one’s inner break-down and submission to another world view) and, moreover, became a man capable of carrying out other people’s orders. Having studied for only 1,5 years, in Berlin he became a professional photographer. After having lived in Germany for seven years, shortly before the First World War broke out, in 1912 he appeared in Russia, in the Urals, in the region of concentration of the defence industry of the Russian Empire. That same year he opened a photographer’s studio of his own and started working. He compiled a card-index of all the prominent residents of Ekaterinburg: administrators and heads of enterprises. We cannot rule out the possibility of his handing over the needed information to the enemy. After all, the Revolution broke out only five years later.From Father’s stories and other available facts and documents, many of the agents either sent to Russia or recruited by the German intelligence service and living in Russia both during the first World war and before World War II, handed over the lists of suspect soviet people to fascists. The consequences are obvious.For instance, a certain head physician of a regional hospital had lived and worked for 17 years in one of the frontier regions in Bielorussia. In 1941, on the intrusion of fascists, he handed over the lists of 100 activists, whom the Germans sent to the gestapo.So, Yurovsky handed over his card-index to the Emergency Commission (ChK) and, using it, the chekists made raids into the apartments of these activists. The scheme of action is the same.In 1914 Yurovsky was called up to the rear units, where, again, he was sent to study. He became a military doctor’s assistant and again served on the home front. Being constantly in contact with the staff of hospitals, with officers and soldiers coming from the front for cure, he gathered the needed information. These and other facts testify to the possibility, that probably, he was not the man he pretended to be. In 1917—1918 there were negotiations with the Germans in Brest-Litovsk. And again, there he was! He provided the guard for the hostages, that is, the family of Emperor Nikolas II. First, the Emperor, the Empress and some of the children were brought. Tsesarevich and his sister remain in Tobolsk. Why? After all, the main problem was not to leave the Emperor’s heirs alive. It means that at that time the problem of paramount importance was to negotiate with the Germans. Thus, a direct communication during negotiations with the Germans was carried out via Yurovsky. So, after the Emperor’s refusal to surrender Russia to the Germans, Yurovsky receives an order to exterminate the hostages. But how? Three weeks before the execution all the Russian-speaking guard and Doctor Derevenko were replaced by German-speaking people. Upon the execution of the Romanov family the German-speaking guards were killed — there were five of them. The Russian-speaking people are blamed for the execution, while contrary to everything they have rescued part of the family of Emperor Nikolas II. Yurovsky carried out the enemy’s order. Then he takes the jewels and three vans of royal robes and sets off for Moscow. And Tsesarevich Alexei lives in Shadrinsk at the Filatovs’. Of interest is that the Filatovs and certain Yurovskys are neighbours. Who are they? On February 24, 2000 we received an answer from the Shadrinsk municipal archive which read: in the fund of the Shadrinsk municipal uprava (administration), the sorting register to the municipal budget as of 1915 contains several real estate owners named Yurovsky. Almost all of them are former peasants, natives of the Makarov district, Shadrinsk region: Peotr Andreevich, Ivan Andreevich, Emel’an Yakovlevich, Ivan Ivanovich, Peotr Alekseevich, Ivan Osipovich, and Anna Kirillovna Yurovsky1. It is difficult to determine to-day whether they had been that Yurovsky’s relatives, but such a coincidence does exist. Relatives? It means that they had had no contacts with that Yurovsky. Yurovsky’s ancestors had been exiled to Siberia for theft and the relatives did not like him very much for his cruelty and for his attitude towards them

In 1918—1919 Yurovsky was the chief of a regional department of Moscow ChK doing undercover work. In 1919—1920 he returned to Ekaterinburg and, again, did undercover work in ChK. In 1920 he was appointed the chief of Gokhran and again he was admitted to State secrets. In 1923 he was responsible for a secret operation on the transfer of the Russian crown, globe and sceptre to a Japanese Agency in China for their subsequent sale to America and Europe via Manchuria. He ruined this transaction. A leakage of secret information took place. Yurovsky was relieved of all his duties. He was deprived of access to State secrets. After this he worked at various enterprises not connected with any secrets. He died in 1938.Not until 1950, was there any mention of him. Then his children started talking about his deeds. Such is the fate of this figure. His biographical material can be found in the party archive of Sverdlovsk, now Ekaterinburg (f. 221, inv. 2, c. 497) as well as in the journal “Nashe Naslediye” (Our Legacy) (1991, №2, p. 40—41; №3, p. 47). In 1961 father told me about participation of Yurovsky in the execution of the Tsar’s family

It is still unclear why Yurovsky being a professional photographer, had not taken photos of the Romanov family members either before the execution or at the execution scene. And if he had done so, where are those photos? Investigator N.A. Sokolov recorded the story of the Strekotins. Both the executioners and the utside guard participants also mentioned the Strekotins. It was they who knew who stood where, and who was doing what. But neither the Whites nor the Reds interrogated them and Sokolov himself does not quote them as principal witnesses whose stories had served as the basis, apparently, for the Whites’ inquiries. The Strekotin brothers had been at Dutov’s front and then they returned to the environs of Ekaterinburg, where they lived, and later were deployed in the guard of the Special House. There remained reminiscences of Alexander Strekotin of Nikolas II’s family, a description of the appearances of the members of the stately family and their style of behaviour in everyday life. Father said that the fate of one of the brothers, Andrei, was tragic. Alexander Strekotin had told father about it during the Civil war, when he came for a short time to Shadrinsk. This testifies to the fact that he had been acquainted with the Filatov family members either before the above-mentioned events took place or that they got acquainted in Ekaterinburg. So far, there is no other conclusion

Andrei Strekotin died on July 18, 1918 from a stray bullet on River Iset. Father had told me about his death (of course, as heard from Alexander Sokolov): “It happened on July 18. They were sitting in a little trench by the Iset River. At that time the fighting was located at the approaches to Ekaterinburg. Andrei said to Alexander: “I am heavy at heart, Sasha; I feel that I will be killed today. Let’s embrace by way of farewell.” — “Andrei, what are you saying? Stop it!” — “No, Sasha, I feel it.” They embraced. Then Andrei put his head out of the trench and a stray bullet hit him straight in the forehead.”

From Alexander Strekotin’s stories, he remained alive only because he went to the forests with N.D. Kashirin, Commander of the partisan detachment, who went with him as far as Perm, and the Kungur caves. Then he worked as a stableman in the Party regional committee in Ekaterinburg. Later on he headed the Machine-tractor station (MTS). He was a family man. In 1988 his wife was still alive. On January 22, 2000 Alexander Strekotin’ relatives who lived in Ekaterinburg, called us up. They told us that uncle Sasha died a mysterious death in the early 60’s, falling out of a carwhile it eas moving. His three sons have also disappeared. All this happened when Father told me about the fate of the Tsar’s family and the execution. In the early 60’s we also left the Urals for northern Russia

They started searching for father both abroad and in Russia. I learned about it from Mr. Spelar, a publisher, secretary to Princess Irina Yusupova. It was in November, 1999, when I was in New-York. When I signed my book, he told me about it with a mysterious air. I asked him: “Why did you search for my father? Did you want to help or kill him?” There was no answer. Quite a number of discoveries and documents that are now collrcting dust on the shelves of both Russian and foreign archives, await those who investige the last days of the imperial family

A remark of Swedish writer and translator, Staffan Scott in his book, Romanovs, deserves notice: “…of a once numerous branch of Konstantinovichs no one man has remained (except perhaps two of the Romanovs, who disappeared after the Revolution but remained miraculously alive in the Soviet Union).” (Scott S., The Romanovs. 1989, Ekaterinburg: Larin Publ., 1993. P. 22). It should be noticed that this book was published in 1989 and, surprisingly, this event coincides with the publication in Russia of the book of E. Radzinsky “Gospodi… spasi i usmiri Rossiyu” (God… save and quell Russia), which also contains information about rescue of two children, the children of Nikolas II — Tsesarevich Alexei and Grand Duchess Maria. What could this be? A coincidence or an established fact? Staffan Scott does not say any more about the rescue of two Romanovs in his book. Even when writing about his meeting with a relative of these children, Vera Konstantinovna Romanova, that is, Konstantin Romanovich’s daughter. In the chapter “The Soviet Union and the Romanovs” Staffan Scott writes: “The attitude of the Soviets to the Romanovs who have survived the Revolution, has also changed compared to stock accusations of the generation of the time of the Revolution. The Soviet secret police — ChK, NKVD, KGB, etc. — have never shunned attempts on the life of Russian politicians in exile or turncoats. But nobody heard either about attempts on the life of the living Romanovs or about their kidnapping. Since they are of no political threat to the soviet system, they do not persecute them — unless we count the rare attacks against pretender Vladimir Kirillovich. We also know that there was no veto for the Romanovs to visit the Soviet Union. From the early 60’s many members of the dynasty have visited the USSR as tourists, including Nikita Nikitich, a historian. Soviet people, whom they met with, treated them with well-disposed curiosity.” (Scott S. The Romanovs. P. 272—273)

So, the executioners are packing the wide double-doors. Strekotin is close by. (What did he want to see there?). That’s what he saw. “… Yurovsky: Alexei and his three sisters, a Romanov maid, and Botkin were still alive. We had to finish them off. The bullets, surprisingly, rebounded off of something and, like hail, were jumping all over the room. — The executioners were shooting as madmen. The light from electric bulb could hardly be seen through the smoke from the gun powder… Figures lying in pools of blood –on the floor, a strangely surviving boy streached his hand to protect himself from the bullets. (Auth.: “After the execution he was not undressed, he was also in corset. His corset has never been found.”). And Nikulin, terror-struck, kept shooting him”. 1 Later on, in checking whether Tsesarevich Alexei had a corset, it turned out that two corsets with jewels had not been handed over by Yurovsky to the depository, that is, there were neither the bodies of two of the children nor two corsets at the burial site. How’s that? If they killed the children, they ought to hand over the corsets with jewels, but did not do it. From Yurovsky’s record (GARF, f. 601, inv. 2, d. 35): “… My assistant used the whole clip of bullets (the strange survival of the Heir can probably be attributed to his inability to handle a weapon or to unavoidable nervousness caused by long trouble with Tsar daughters)”. But the most incredible thing is that the bullets could have been blank cartridges. It is unclear so far, whether the present inquiry has made a ballistic examination. The executioners are known to have given their weapons to the Revolution Museum. The investigator ought to have ordered a ballistic examination, and the experts were to have shot bullets from these weapons, and then to have compared them with those found in 1919 at the burial site near Ekaterinburg. And if they do not coincide in their characteristics, then they are not those weapons and the people were killed by the use of other weapons, or these are the bodies of other people. And the version worked out by the inquiry is wrong. Other explanations to these facts should be found rather than to follow a mistaken path. The book of investigator Sokolov N.A.2 gives the interrogation of Pavel Medvedev: “Blood flooded the floor. When I entered the cellar the Heir was groaning. Yurovsky approached him and fired at him two or three times, point-blank. The Heir quietened down. It made me sick.” From the reminiscences of Andrei Strekotin cited by Platonov O.A.3 in his book: “All the prisoners were lying on the floor already, bleeding to death, but the Heir was still sitting on the chair”

A participant of the execution, 18-year old Netrebin Viktor Nikiforovich records: “The Heir still showed signs of life though a lot of shots had been made…». Recollections of Andrei Strekotin: “Then Ermakov, seeing that there was a bayonet in my rifle, suggested that I stabbed those still alive. I refused. Then he took my rifle and started stubbing them…” (Sverdlovsk Party Archive, f. 41, inv. 1, c. 149, p. 164. References to the archive have been taken from O.A. Platonov’s book). “The shooting stopped. The door was opened to clear the gun-powder smoke… They began to remove the bodies. First the body of the Tsar was removed. The bodies were piled up in a truck.” Andrei Strekotin describes how the bodies were removed, in which order, and he knew exactly when it would be the Heirs’s turn. He had told his brother Alexander that the Heir was the last one taken out and the last one laid in the truck, since that night Alexander did not return to the Ipatiev house. Was the end gate of the truck closed? How high were the sides of the truck?

“There was not enough room in the carts for all the bodies (Auth.: “The truck got stuck five miles from the town, near the Upper-Iset plant».).There were not enough carts which worked well. They were falling apart. (It was already 4:00 or 4:30 in the morning. Who was loading whom? And where to?” — author’s remark). Then it turned out that Tatiana, Olga, and Anastasia had some corsets on.“1

When the funeral team noticed during the transfer of the bodies that some bodies were missing, they feverishly began to feel the pulse of the remaining bodies because they understood that those missing remained alive, and only at that moment did they find out that. Tsesarevich Alexei and Grand Duchess Maria were missing, as well as two corsets. That’s why nobody of the funeral team had mentioned in their memoirs that there were two missing children and two missing corsets. That’s why the truck went on to the shaft carrying only part of the bodies. It turns out that there was no post-execution search. Apparently, there was no time. But why? If the executioners knew the Romanovs by sight? Maybe, it had already grown light and they had to hurry? (They did not search Tsesarevich, his mother and other bodies). The conclusion is the following: it means that the escort had lost the bodies before the pause near the Upper-Iset plant and nobody had noticed it. That was an enigma. Father’s words were confirmed. The stealing had begun. In Radzinsky’s2 book Yurovsky says: “I decided to dismiss the team immediately, leaving only some sentries as a guard and five men of the team. The rest left…” Where did the rest go? And what for? When they did not know at all what to do. Did they understand only at that moment that two were missing or was it before? Did they go searching in the dark? Apparently, the jewels were also registered in the dark… Our father was terribly maimed. His back had many scars of various sizes. The scars were 1.5 to 5 cm. The scars in the center were up to 0.8 cm high. There were also scars to 10 cm. There was a shrapnel wound on the left heel, the scar was cross-shaped. Two ribs were broken. By 40 years his left leg was withered and by 1944 became shorter than the right one. On the whole, there were up to 20 scars and bluish dents in his back. Father would buy shoes of different sizes: 40 for his left leg and 42 for his right leg. Because of the wounds, by 1944 his spine had become twisted to the right. We, when children, would ask him about his wounds and disabilities. He would tell us that he had gone to the Finnish war in a coach, but the planes had bombed the train and he, without reaching the front, returned to the hospital. And to the question what he was and why he was in the army he answered that he was a student in Leningrad and all students were called up. Or he would say that he was such from birth, or that he fell from a tree. Such were his answers until we grew up. Later on we understood that those had only been excuses and the reason of his wounds had been of quite another nature. According to the records in his serviceman’s identity card, in 1942 he was exempt from military service. There are no records for other years. So, he was not at the front. At any rate, our family has not got any relevant documents, also. There is no disability certificate. From the evidence of F. P. Proskuriakov, a guard: “… When all of them had been executed, Andrei Strekotin took off their jewels. Yurovsky confiscated them and took them upstairs…“1. A question arises. Everything was in gunpowder smoke (the guards were sick, they ran out in the open air and vomited). There was no doctor who could confirm the deaths. Strekotin had a revolver, was he going to gather the jewels in everybody’s presence? Or, maybe, there was nobody else?

At that time, if Andrei Strekotin, feeling Alexei’s pulse, understood that he was alive, he could have put his revolver into Alexei trousers pocket, in the boot or slippped it into his bosom. Father would tell us that there was an understanding in their family — if they were faced with a military threat, somebody would hand him over either a weapon or a knife should the opportunity arise. On that day a sign will be made with a white handkerchief. It was to be made by whoever would chance to be on the outside guard during the walk of the family: usually Andrei Strekotin would stand at the watch-tower by the machine-gun. Later on father told me that after the truck had stopped near the Upper-Iset Lake, the boy regained consciousness? He was lying on the ground and it was raining. He decided that it was necessary to crawl from that place, as far away as possible. The boy crawled under the little bridge and, lying there, tried to think out where he should go to. Searching himself he found a weapon. This lent him vigour and energy. Reaching the railway branch the boy hobbled towards the station Shartash. Father went on: “By the morning he was already at the station and here the patrol saw him. They were seven. Remember, Oleg, they were seven. And they urged him on stabbing him with bayonets in his back. They did not understand Russian, apparently, they were “nekhristi”. And here father suddenly said: “You know, it hurt very much.” I listened to him without saying a word because he ought not to be interrupted. Otherwise he could fall silent and say not a word, ask him as you might, till he himself wanted to tell something new. Of course, I understood that he was speaking about himself. Then father said that he could not resist them anymore but said to his tormentors that he would not give himself up alive. A switch woman, who was at that time at the station, saw the patrol took the boy away from the station, in the direction of the forest, and cried after them: “Where are you taking the boy to, monsters?” In answer they threatened that they would shoot. They threw him into a shaft. It was not deep. The boy hit his head against a log and slipped down. Where to go to? Then he saw a horizontal shaft and dove there. The tormentors threw a grenade after him, and some shrapnel hit his heel. So the scar on his left heel was caused by that shrapnel. Four hours later the Strekotin brothers came after him on the hand-car carried him out of the shaft and took him to the hospital. After they gave him first aid they took him to Shadrinsk. How could it happen? It’s simple — nobody had searched for the bodies. Apparently, Alexander Strekotin was not in the house at that time. Nobody mentioned him. Where was he? Radzinsky E.S.1 gives Andrei Strekotin’s recollections in his book: “When the bodies had been removed and the truck had gone, only then were we dismissed.” It was at 3:00 a.m. on July 17, 1918

What did Alexander Strekotin do at that time? He was mentioned first in the case of investigator Sergeev (Sokolov’s book “Ubiistvo tsarskoi sem’i’- The Murder of the Tsar’s Family). In E.S. Radzinsky’s 2 books Medvedev, the son of the Chekist, says: “In the morning, when my father arrived at the market, he heard the story in detail from local market-women, where and how the bodies of the Tsar’s family were hidden. That’s why the bodies were re-buried.” In means that information from the Ipatiev house appeared in the town either at night or in the early morning and so, the Strekotin brothers, the Filatov brothers, and Mikhail Pavlovich Gladkikh had known everything beforehand, let alone Kleshchev and Shulin, who were in the Ipatiev house at that time. It is of interest that Andrei Strekotin described in detail both the family and the execution; hence, he had been deeply impressed by everything. Besides, he had a good memory. The White investigators did not find Alexander Strekotin because he did not stay in the town but went away to the forests. Alexander was outside the Ipatiev house. That night the time factor was very important, i.e. time was needed to send Tsesarevich to Shadrinsk and it was necessary to cover their tracks so that nobody would know that he, Strekotin, helped him, together with other soldiers. It should be emphasized that the officers of the Russian army General Staff were at that time, from May 1918, in Ekaterinburg and took an active part in the preparation of the Romanov’s rescue. Facts are given in the book “Tainy Koptiakovskoy dorogi” (Secrets of the Koptiakov Road) 1. “In May 1918 the former Nikolas Academy of General Staff was moved to Ekaterinburg. It was quartered not far from Tikhvin Monastery located within the town. The senior grade had 216 students, only 13 of them later fought for the Soviets. Most of them considered the Treaty in Brest treason. In Ekaterinburg they found themselves in hostile surroundings. Besides, comissars: S.A. Anuchin and F.I. Goloshchekin, of the Urals regional Soviet, considered the presence of “an organized center of counter-revolution”, under the guise of an Academy, in the very center of the Urals, inadmissible. By June 1918 the Academy had 300 students, 14 professors and 22 teachers on the staff. With an advance of the Czechoslovak troops the Academy was moved to Kazan by the order of Trotsky. But less than half of the students, declaring“neutrality”, moved there. Later almost all of them went over to Kolchak’s army, and the Nikolas Academy existed no more. It seemed that the 300 regular officers, who were in Ekaterinburg in June-July 1918, could not form a striking force to rescue the Tsar’s family. But today it is questionable. Where is the documented evidence of what the “uncovered” organization of officers did for the rescue and who else did they include in the rescue? And if it did save somebody, nobody would say a word about it. For he, who states it, not only did not serve in the army, but also knows neither operational work nor the methods used by the tsar’s secret service, let alone practical knowledge of secrecy. The level of training of the Russian officers was too high, especially of those who graduated from this Academy

So, after the town was annexed it turned out that there was a secret military organization of the officers among the students of the Acedemy. The following captains were in this organization: D.A. Malinovsky, Semchevsky, Akhverdov, Delinzghauzen, Gershelman, Durasov, Baumgarden, Dezbinin. Via Dmitriy Apollonovich Malinovsky the organization had made contact with the monarchists in Petrograd. It was systematically in great need of money. Captain Akhverdov’s mother, Maria Dmitrievna, took part in this organization. The officers contacted Doctor Derevenko. They tried to get the plan of the Ipatiev house. Lieutenant-colonel Georgiy Vladimirovich Yartsov, chief of the Ekaterinburg instructor’s school of the Academy, testified the following on June 17, 1919: “There were five officers among us to whom I frankly spoke about taking some measures to rescue the Royal Family. These were: Captain Akhverdov, Captain Delinzgausen, Captain Gershel’man. We tried via Delinzgauzen to get the plan of the Ipatiev apartment where the Royal Family was kept.” (He succeeded in getting the plan via Doctor Derevenko who described to him orally the lay-out of the rooms). “Later I myself happened to be in the Ipatiev house and saw that Derevenko had given correct information.” (The officer, accidentally or carelessly, had practically given Doctor Derevenko away. Thus, if this document reached the Reds, then it is no wondered that in 1924 Doctor Derevenko was summoned to ChK in Perm and in 1930 he was arrested and spent his last years in the concentration camp.) 1 For the same purpose we tried to establish contacts with the monastery which supplied the Royal Family with milk. Nothing substantial came out of it: it could not be done, first, because of the house guard and, second, because we were followed. I remember that on July 16, I was in the monastery. On that day the milk was delivered to the house. The head of the photo-section of the monastery the nun Augustina said to me that the soldier said to the nun who brought the milk: “Today we shall take the milk, but to-morrow do not bring it, there will be no need” (Auth.: “That is, he notified her”). I do not remember the things we found in the shaft, apart from those I mentioned. All these things were taken by Captain Malinovsky to be stored”. Captain Malinovsky also mentioned it in his records. He described an exact lay-out of the rooms where the Royal Family members lived, namely, who and where. Then he says that he was one of the first who got into this house after the annexation of the town. He said that there was also a student kept in this house who twice took photos of the house. “…Akhverdov’s man-servant was also a source of information (I know neither his name nor his surname. It seems to me that it was Kotov). He got acquainted with a guard and learned something from him. … I informed our organization in Petrograd sending agreed telegrams in the name of Captain Fekhner (an officer of my brigade) and Riabov, esaul (sergeant) of the combined Cossack regiment. But I never received any answer.” This phrase of Captain Malinovsky shows that the officers’ organization had branches about which Malinovskysaid little. It means that, probably, the organization had been formed before the departure of the Academy from Saint-Petersburg, and the officers told even the White inquiry neither about the number of participants in the organization in Peterburg nor how long it existed, what it did in general and whether they had contact with it later on. It was because the officers were afraid for the life of their people and for the activity of these branches, which could still be effective for a long time in the future, supplying with useful military information and serving as channels to take people to safe places in case of failures. Besides, among the White investigators could be those who worked in the interests of the Red or somebody else. It was the war. The point was that the Tsar’s family should be rescued, and members of the organization did not know all the information because they knew that they should think about security in this dangerous work. All of them risked their lives and the lives of their relatives. “I would say that we had two plans, two goals. We had to have a group of people who at any moment in case of the expulsion of the bolsheviks could occupy the Ipatiev house and guard the safety of the Tsar’s Family. The other plan consisted in a daring attack of the Ipatiev house and taking the Royal Family away. Discussing these plans we drew seven officers more from our Academy. These were: Captain Durasov, Captain Semchevsky, Captain Miagkov, Captain Baumgarden, Captain Dubinkin, and Rotmistr Bartenev. I forgot the name of the seventh. This plan was utterly secret and I think that the bolsheviks could not learn about it. For instance, Akhverdova knew nothing about it… Two days before the occupation of Ekaterinburg by the Czechs I, among 37 officers, left for the Czechs and on the next day after the occupation I returned to the town.” “Note that Nikolai Ross (1987) who published the cited part of Malinovsky’s evidence cut off the end of the protocol recorded in 1919 by N.A. Sokolov. Captain Malinovsky believed that the Germans took the Family to Germany, simulating an execution.“1 However, there are documents in the State archive of the Russian Federation which testify to the fact that not everybody agreed that all the members of the family had been killed. So, as Fyodor Nikiforovich Gorshkov from Ekaterinburg said, officer Tomashevsky asserted that the execution took place in the dining room and that not everybody was killed. Doctor Derevenko, as investigator Sergeev said, also believed that somebody remained alive. Incidentally, Sergeev himself was of the same opinion. N.A. Sokolov’s report on the inquiry into the murder of the Tsar’s family in the Urals is known to have been sent to widow Empress Maria Fyodorovna who till her death in 1928 beleived that her son Nikolas II and grandson Tsesarevich Alexei remained alive. She had written about it to Marshal Mannerheim in Finland. In this report N.A. Sokolov writes: “… Jewels sewn to clothes as buttons had, apparently, burned. The only diamond was found on the outskirts of the fire trampled into the earth. It (its setting) was slightly injured by fire.”… These words do not hold water. Carbonaceous compounds such as diamonds cannot be damaged by fire. These conclusions are incorrect. If Sokolov did not find what he was searching for, it means that the people had been annihilated. But maybe they had been rescued? Who had rescued them? Sokolov is known to have left this version out of his account. Why? What prevented investigator Sokolov N.A. from inquiring into the version of the rescue of part of the family of Emperor Nikolas II?1 Today we know information about the people who had rescued Tsesarevich Alexei Nikolaevich Romanov and who had named him Vasily and had done everything for him to live and work. It was the middle-class family of Filatov K.A. in Shadrinsk. What and who was he? The Filatov family — Ksenofont Afanasyevich Filatov and Ekaterina, his wife — could have refused to take a wounded boy into his family if they had not been prepared for this morally. They had a son born in 1907. In 1937 Vasily Filatov mentioned in his biography that his mother and brother died early2 and by 1921 he was alone. Though he had two uncles who served in the Red Army and disappeared