Бесплатный фрагмент - Refusing to Love

The Paths of Russian Love from Pushkin to AI. Part I — The Golden Age

About the book

Dedicated to my lovely children Egor, Darya, Ilya, and Anna

In our previous book, Enjoy, Comprehend, Love: Entering the Spaces of Conscious Love, we explored the idea that love can be befriended by the mind, making it conscious and meaningful without losing the emotional intensity and vivid experience of love. The image of a journey through the spaces of love was the linking framework of the book, and spatial metaphors were used to describe the complex, paradoxical manifestations of the relationship of love.

In this new book we offer the reader a journey through time to the origins of the phenomenon of Russian love and a walk along its winding paths in the company of famous classics of Russian literature. In the course of the narrative there are references to various features of love in France and the United States, allowing the reader to get an idea of the international love triangle.

The book consists of three parts: the Golden Age, the Silver Age, and the Torn Age. The first part presents three vectors of Russian love, each illustrated with examples from the works and personal lives of the writers. The Romantic vector of Russian love is based on Pushkin, Lermontov, and Alexey Tolstoy; the aspirations of reason and freedom are in Herzen, Turgenev, and Chernyshevsky; the immersion into the depths of the human soul is characteristic of Dostoevsky, Leo Tolstoy, and Chekhov.

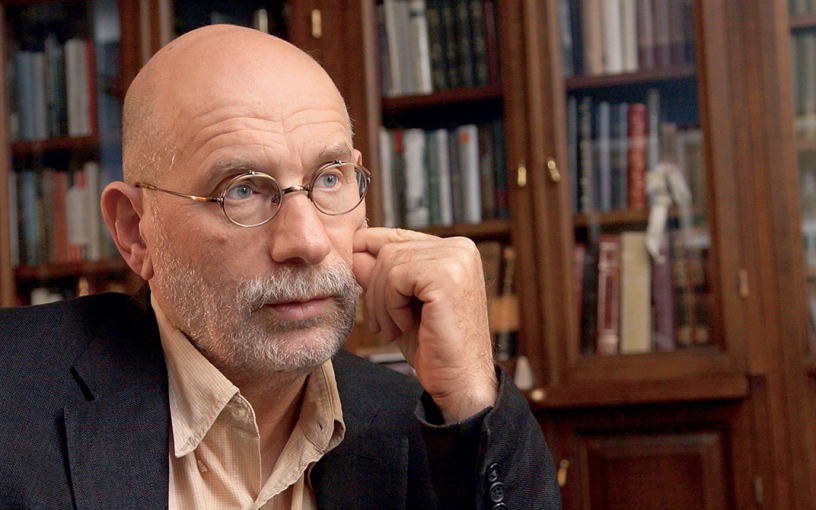

The first part wraps up with the concept of love of the famous contemporary Russian writer Boris Akunin, presented in the series of works «Family Album» published in 2012- 2022.

I

An obnoxious discovery. Tempest in the web. An accidental connection. Transparent hints. A voice in the digital wilderness. The past in the present. Vices and prophets. A roll call from across the ocean

Approximately three hundred years ago in the early eighteenth century, love appeared in Russia. In the time of Peter the Great, according to the famous Russian writer Boris Akunin, it was «brought to Russia by foreigners along with allonge wigs, earthen apple and coffee.» He made the discovery in 2012, finding the absence of «old-Russian love vocabulary» in the ancient sources, and boldly breaking the laws of strict logic, published the original conclusions in his blog.

In the web unfolded «not a joke, but almost a scientific discussion.» Someone did not understand the light irony of the writer and in all seriousness advised of the historical events in Russia, colored with passion. Some stood up for love, proving its inseparable existence with the human race from biblical times. Well, some took it upon themselves to accuse the writer of liberalism and historical illiteracy, while at the same time mentioning for some reason that «he walks on the boulevards against the authorities.» Significantly, and as we may also presume far from accidentally, the question of Russian love’s autochthonousness emerged from oblivion and was sharpened precisely in the midst of the Boulevard Revolution in Russia, which sparked but soon extinguished. Surprised by the activity of the netizens in defense of the Russian love’s honor, the writer considered it prudent to point straightforward ladies and perpendicular gentlemen to his literary trolling, but nevertheless he did not refrain from hinting that his tale about the Russian love has some truth, having pointed to the well-known history of the appearance, disappearance, revival, flowering and spread of the European love, also mentioning that it is actually about the «sublime love».

One sincere commentator, trying Akunin’s idea of the absence of love in ancient Russia on the contemporary reality, reported that it does not exist even now. This skeptical contribution to the spontaneous discussion was apparently made, if not implied by something purely personal, by a rather observant person who also had in mind not just the impulses of sex, but precisely true love, which can only be of one «freshness» — high. Sometimes even an indirect shift to personalities can bring a sensitive fresh breeze and turn a mass exchange of opinions in a radically different direction. But the point that sharpened the discussion was ignored: the network’s patriotic activists were frothing at the mouth to defend their romantic past, not caring in the slightest about the state of tender feelings in the observable fatherland.

And in vain. Ten years later, Russian society, lulled by the sweet-talking leaders with ideas about their own greatness, will have gone beyond the boundaries of humanity and plunged into a time of troubles, when even the most flexible minds will only be perplexed and try in vain to find the missing links in their once graceful explanatory concepts. Back then, no one ever thought that a society that omits love from its life and replaces it with surrogates in all niches — from pop bohemia, New Russians with their glamorous girlfriends, the masses hooked on beer and jerk humor, to the ambiguous marital status and sexual orientation of the top officials of the state — is doomed to a slide into its most sad and pernicious vices. And first of all, those who, due to the duty of their professional role, were charged with propagating the divine revelation that only love can truly resist sins, diligently closed their eyes and loyally erred.

In the same year, when the lines of true love and the dignity of the inhabitants of a vast country crossed in the creative life of one Russian writer, Marilyn Yalom’s book was published in another outstanding country in many respects with the echoing title: «How the French Invented Love: Nine Hundred Years of Passion and Romance.» The book told Americans that there is a kind of sublime love that in human history originated almost a thousand years ago in France, took a winding path, became an integral spiritual part of the French and still makes itself felt in one way or another, for example, in a baisemain, a kiss of the hand when meeting a woman.

II

Love Triangle. The American Angle of Love. The Yalom family as the prism of American society. A grafting of the world’s best patterns. The therapy of love misery. Techniques of normative love. The living connection of times and spaces

Let us see where this seemingly random line of coincidence of questions about the origin of love can lead us. We are facing a peculiar international love triangle: love was invented by the French, this ancient invention excites modern Americans, the Russians deny love inoculation from outside and proclaim their own special kind of love. Perhaps these three different abodes of love can serve as quite exhaustive sources of information about what is wanted of it, how it is treated and how love survives in the modern world.

Since we have the American angle of love, let us sketch it in general terms. To get an idea of its gradations and formative vectors, we simply need to get to know Irwin and Marilyn Yalom and their areas of interest. The issues that Marilyn dealt with professionally lay in the field of gender studies and the history of the position of women in societies of different cultures. In particular, she wondered «how marriage, once considered a religious duty in medieval Europe, evolved into a sense of personal fulfillment in contemporary America.» Marilyn’s Stanford University colleagues noted her fascination with «the 18th-century French salon culture where women played a leading role in organizing events of intellectual discourse,» and her attempts to instill these traditions in her community.

Her husband is a well-known existential psychotherapist who has observed the experiences of his patients as they face the inevitability of death, as they face isolation in their own inner world, as they struggle with life choices, and as they strive for love. Summarizing his findings, Irwin Yalom reveals the tragic disconnect inherent in Americans between their trust in love and their destructive dependence on love. The cause of love’s frustrations lies in the relaxed perception of love as a spark of spontaneous infatuation and exclusive strong attachment. Such closed love is doomed to self-destruction. True love, according to Irvin Yalom, «is rather a form of existence: not so much attraction as self-giving, a relation not so much to one person as to the world as a whole.»

To generalize the American angle of the love matters, there is a desire both to import the world’s best examples and to invent original formats of love, as well as a preference for getting rid of love diseases and achieving some kind of normal state of love with the tools of some pragmatic scientific or pseudoscientific school of psychotherapy.

Irvin Yalom himself would hardly have had the opportunity to experience the joys of family longevity if his parents had not immigrated from the Russian Empire in the midst of World War I. At the same time, the Silver Age of Russian spiritual culture began to decline, completing the long cycle of the Golden Age of its heyday, the beginning of which matured in the circles of the then high-society (aristocratic) community, inspired by French fashions and customs, as well as a military victory over the ruler of the minds — Napoleon.

III

From ship to ball. Elegant pas of tender feelings. The new framework of love. The cult of striving for the ideal. Faces of beauty. Incarnations of romantic dreams. The imaginary reality of the ideal. Divine creation

If one were to imagine a time-traveling explorer setting off after meeting the Yalom couple to the origins of Russian love, he would certainly get to a large formal gathering for social dancing, where he would meet Pushkin, Lermontov, and other participants and chroniclers of the heyday of the Romantic era in Russia. The ball was the center of love — romantic fantasies matured in anticipation of the ball, during the dance signals of attraction were transmitted and sparks of lofty feelings flashed, after the ball the trajectory of romantic experiences rushed on the wings of found hope up or plunged into the chaos of mental turmoil.

It is safe to say that love ruled the ball, as well as the fact that the ball ruled love — made up its entourage, set the style, manners, patterns, and established the unspoken rules of love. To imagine the romantic atmosphere of a ball can be contrasted with the suppression of open expression of feelings and sexual desires in the Middle Ages era, famous for religious asceticism, accusing beautiful women in satanic sins, the church regulation of marriage. However, the spirit of the ball was also alien to the rigorous reasoning and cold mechanicism of the Enlightenment, which prevailed over the «dark ages.» The high society, exposing itself at balls, welcomed, within certain limits, the freedom of feelings and manners, but considered a demonstration of intelligence excessive. An exception was made only for geniuses, especially poets. But their position in high society was unenviable, since social status and, consequently, the attractiveness of the groom was still determined by wealth, nobility and government rank.

All these special features of the new environment, in which young minds and hearts were immersed in the early 19th century in Russia, formed a fairly slender and ramified model of culture, which is now called romanticism. In romanticism, everything is permeated with the cult of the ideal and awe of feelings in the pursuit of it.

The ball seemed to be the earthly embodiment of the desired ideal, where it could be encountered by chance or found after making the necessary preparations. It presented faces of beauty, models of grace and perfection, nobility and dignity — everything that the human soul sooner or later aspired to and longed for. The imaginary reality and visual proximity of the ideal made the heart beat faster, excited the blood, generated plans for the realization of the cherished dream and pushed to action to fulfill them.

Along with the expectation of meeting a romantic dream with its embodiment, the ball also set the standards of presentation in the form of the dress code, as well as in the manner of communication, the ability to dance and maintain small talk. Some of this set could be bought and some could be learned, but most of all natural beauty was appreciated, which was perceived as divine. The great poet Alexander Pushkin became a victim of the passion of possessing such an unearthly beauty.

IV

The poet and love. A genius of pure beauty. The consonances of divine harmonies. Lyrical hero. Tragedy of loneliness. The emptied heart. The science of tender passion. The fateful lot

Even before he met Natalia Goncharova, Alexander Pushkin, judging by his own" Don Juan list», repeatedly admired the manifestations of divine beauty, which he noted in the women he knew and the amazing feelings they aroused in his soul («and divinity, and inspiration, and life, and tears, and love»). At the age of 25 he wrote his famous poem:

I can recall that magic moment

When you first came into my sight

Like fleeting vision, like an omen

Of pure beauty and delight.

The poet’s soul is like a unique musical instrument tuned to the consonances of divine harmonies. The inspiration generated by contemplated beauty is united with love. All facets of love — attraction, closeness, affection, understanding, admiration, enjoyment — are blessed with inspiration as the highest thrill of the soul. (It is no coincidence that lovers write and read poetry to each other.) Take all this to a high degree of mental acuity and art talent, compare it to the poet’s surrounding reality, and you get a picture of a fate doomed to the tragedy of solitude.

«The Romantic conception of man proceeds from the notion of his oneness, isolation, wrenching from all earthly ties,» noted the famous cultural scientist Yu. Lotman in his analytical essay on the poets of the 19th century and pointed out the essence of the tragedy of their lyrical heroes, which «consists in the contradiction between the attempts to break through to another „I“, the desire for understanding, love, friendship, connection with the people, appeal to posterity and the impossibility of such contact, because it would mean the loss for „I“ of its exclusivity».

In this vein, the depth of experience arising from the desolation of the heart as a result of a series of infatuations and disappointments, expressed in Alexander Pushkin’s poem written in 1821, becomes understandable:

I have endured my desire,

I’ve ceased to love my fairy dreams,

And only fruit of hearty fire —

My sufferings have stayed, it seems.

And under storms of cruel kismet

My blooming spirit quickly died,

I waited for the end, I missed it.

I’m feeling loneliness inside.

So that enveloped by the blow

Of cold wind and stormy flaws

A leaf which is belated, sole,

Vibrates on bare branch in pause…

There is no doubt that Pushkin’s genius wrapped all facets of romantic love — divine delight, «jealous sorrow» and «yearning laziness» — in a «gilded shell» and presented it to his descendants, who are free only to admire the shiny wrapping or share the bitterness and sweetness of love experiences together with the poet. Along with the ability to respond with all his soul to the heart’s feelings with their joy of divine inspirations from «miserable foolishness» and fear of disappointment from «flaming contagion» Alexander Pushkin described in amazing detail the ability to coldly hypocritically manipulate feelings by the rules of «science of tender passion», which was typical for «young rogue» Eugene Onegin, whom he considered his friend:

How well he donned new shapes and sizes —

startling the ingenuous with a jest,

frightening with all despair’s disguises,

amusing, flattering with the best,

stalking the momentary weakness,

with passion and with shrewd obliqueness

swaying the artless, waiting on

for unmeant kindness — how he shone!

then he’d implore a declaration,

and listen for the heart’s first sound,

pursue his love — and at one bound

secure a secret assignation,

then afterwards, alone, at ease,

impart such lessons as you please!

It seemed that the poet’s earthly path of true sincere love was complete. In 1828 he shared his new state of mind with an old acquaintance: «I confess, madam, the noise and bustle of Petersburg has become completely alien to me — I can hardly bear it.» Friends also notice the change, seeing as previously indefatigable Pushkin «spent whole days in silence, lying with a pipe in his mouth on the couch.» About what «waves, poems and ice» converged in his soul with what «stone, prose and flame,» we can only guess, for example, referring to a mention in a letter to a friend between times about the «genius of pure beauty,» Madame Kern, «whom with the help of God, I f… the other day.» Reflection came to the decision to marry. Surprisingly, these cold-blooded considerations were swept up by love, which suddenly appeared in the life of a poet now as a fateful lot.

V

Flight from love. Towards the northern Aurora. The fears of the indifferent heart. Anticipation of hell. Involuntary sadness. The reliable source of inspiration. Soul rebirth. Black man. Embodiments of romantic poetry

Twenty-nine-year-old Pushkin met the young (sixteen-year-old) Natalia Goncharova — an extraordinary beauty, fell in love, proposed, got a vague answer and… left, driven by «involuntary sadness.» Five months later, having been in the army in the Caucasus, he paid a visit to Goncharov in Moscow, but met with a cold reception. He admits that «for the first time in his life he was timid» and «did not have the courage to explain himself.

Pushkin leaves for St. Petersburg in "utter despair." By the way, he rushed further abroad "haughty running away," but the Russian tsar did not let him go.

Tell me: in my wanderings shall my passion die?

Shall I forget the proud, tormenting maiden?

Or at her feet, her young wrath,

As a customary tribute, shall I bring my love?

Another five months pass, and Pushkin receives the news that he is favored. But this does not bring joy, he sinks into reflection and feels «no longer happy.» And yet he makes up his mind and goes towards the «alluring star of beauty.» Then followed the gaining momentum of events and imminent faces — the re-proposal, marriage, family happiness, children, high-society balls, the chamber-junker rank, participation in the fate of his wife’s sisters, intrigues, Madame Poletika, d’Anthès — culminating in the mortal risk foreseen by him of the embodiment of his fatal love in marriage union.

In a letter to his beloved’s mother a month before the engagement, Pushkin finds it necessary to explain the reasons for his hesitations and fears. Let us leave aside «the question of money,» let us pay attention to the anxiety for «her happiness,» and try to delve deeper into the poet’s own involuntary doubts.

Pushkin believes that he may, in time, excite Natalie’s affection. However, another twist of «the quiet indifference of her heart» is also possible. Admiration, temptations, opinions, and in the end — regret, which can cause disgust for the «insidious kidnapper,» and the thought of it for Pushkin — hell:

She will be told that only an unhappy fate prevented her from making another, more equal, more brilliant, more worthy of her union… Will she not then look at me as a hindrance, as a treacherous kidnapper? Will she not feel disgusted with me?

At the same time, it seems that the reference to the imagined torments of hell is not only related to the fear for her possible misfortune. There is a sense of something missing in the letter, but glimpsed in the writer’s mind. Perhaps it is the concealment of a reason that might lead to the necessity of taking a mortal risk for her sake. But what such a risk for the husband of a pretty young wife can think of a sophisticated connoisseur of manners of high society? It turns out that Pushkin had foreseen the most devastating consequences of his passion, which drove him mad, or rather, led all his reasonable intentions.

And yet coming «black thoughts» are not only connected with the anticipation of possible complications for respectable family life in the full of temptations of the capital St. Petersburg. Pushkin’s anxieties are linked more elegantly with the first part of his letter, where he speaks of the delusions of his early youth, which were «too heavy in themselves» and intensified by slander. We may then assume the following picture of what tormented the poet. In Pushkin’s imagination, the sins of his youth collided with the giddiness of love and enclosed him in their grim embrace. This is indicated by the fact that when he received a vague but hopeful answer to his proposal, he was seized by «some involuntary sadness.» What could Pushkin then involuntarily and wistfully think about? About fortune’s goodwill and a phantom chance to redeem the sins of his «sad youth» or about the impossibility of it, regretting that he had not saved himself in spiritual purity for true love? To all appearances, Pushkin saw in this belated gift of love, albeit an illusory one, the hope of achieving spiritual equilibrium.

Having received the approval of his parents and the sovereign, hastening the wedding, he is «stunned that he can use such an expression» as «my happiness.» Pushkin is full of ideas and creative plans, the muses of inspiration are already tamed and do not require sacrifice. For the full harmony of life, he needed the support of true love, flowing into the warmth of the home and the measured joys of family happiness. Vladislav Khodasevich, who analyzed «Pushkin’s poetic household,» noted three «features of the change that happened in Pushkin» following the engagement with Natalia Goncharova. Known for mockery and contempt for family life («marriage binds the soul»), childbirth and cuckolded husbands, he becomes attentive to these things and «speaks (about them) quite seriously, businesslike, at times sympathetically.» Apparently, in the words of Don Juan from the little tragedy The Stone Guest in November 1830, he described the transformation taking place in his soul.

…of debauchery.

I have long been a humble disciple,

But ever since I saw you

I feel like I’ve been completely reborn.

I love you, I love virtue

And for the first time humbly before it

I bow my trembling knees.

Indeed, the poet’s cherished lyre played in full force — the Boldin cycle of works, then Dubrovsky, The Bronze Horseman, the famous fairy tales, The Queen of Spades, The Captain’s Daughter. But as if there was a second part of the «will of God» or another more insidious messenger of fate, which was inevitably brought closer by the same «secret maiden.»

If now, looking at our sketchy acquaintance with Pushkin, we can deduce the main lesson of his love, it is undoubtedly connected to the change that happened to him, when the romantic hero playing with love is reborn into a servant of true love, a priest of «the one beautiful». On this path, however, he is haunted by his own shadow, his «black man.»

In his diary entries Pushkin follows with interest the development of the scandal surrounding the marriage of Bezobrazov and, perhaps anxiously, tries some of the circumstances on himself. The wedding of the handsome aide-de-camp with the maid of honor Lyubov Khilkova was sponsored by the imperial couple. Soon, however, it became known that the maid of honor was having an affair with the sovereign, that her husband was terribly jealous, beating her, and… a dagger flashed. The story was loud and instructive. For example, P. A. Vyazemsky wrote to their mutual friend with Pushkin: «Here we all complained about the flat prose of our everyday life, but, on the contrary: romantic poetry is made in person and such that it will shut up Hugo and Dumas. Jealousy, the dagger, criminal love, all this is now the currency of our drawing-room conversation, and all the familiar faces and circumstances of yesterday. Who could have imagined that poor Lyuba Khilkova, the cold, sensible, measured, perfect, exemplary piece of ice of the Winter Palace, would be the heroine of such a tragic tale! So much for the marriage of love! Now none of the girls would dare to marry for love.» He was exiled to the Caucasus, she went to her brother in Moscow and four months after the wedding she had a miscarriage.

In 1837 Mikhail Lermontov, who became famous for his defiant poem on Pushkin’s death, was exiled to the Nizhny Novgorod Dragoon Regiment commanded by Bezobrazov. And four years later Bezobrazov would come to Lermontov’s funeral and carry his coffin.

VI

The relay of Romanticism. Love-passion. The two ways of romantic love. Love-aspiration. The kidnappers of love. Faithful dreams. Flattery instead of love. Passing the baton

Young Lermontov delved into Pushkin’s «wonderful songs», rewrote poems, and shared with Pushkin his knowledge of people. At the same time, Lermontov was distinguished by close attention to his own mental states, the depth of which he discovered in a combination of feelings of love and awareness of his sharp mind and poetic talent. All the turbulent events of his youth turned into a struggle of internal forces in such a way that he found «the root of torment in himself.» For Lermontov, love is the strongest passion, the focus of his heartfelt impulses as an expression of the true «I»:

Many lovers do not trust the world

And so are happy; others feel desire

Engendered in their blood and outwards swirled

In brain disorder or creative fire.

Love, of all the passions, most divine;

Yet, a thing I never could define!

Seems a love can take but one sure course:

At fever pitch with all my psychic force!

And in the proud soul of the romantic hero, vain rejected love will undoubtedly «revolt, breathing revenge»:

From now on I will enjoy

And in passion I will swear as a boy;

I will laugh with everyone

And I don’t want to cry with anyone;

I shall deceive without misgivings,

To find no love as I once made, —

How can I respect other women

When I, by Angel, been betrayed?

Yu. Lotman, analyzing the work of Lermontov, points to two ways of love of the romantic hero. Firstly, the romantic scheme of love contains “the impossibility of contact: love always appears as deceit, misunderstanding, betrayal.” Secondly, “the impossibility of breaking through the line of incomprehension in love created, next to tragic real love, an ideal love-aspiration, in which the object could in no way be endowed with the features of an independent personality: it was not another ‘I’, but an addition to mine ‘I’ — ‘anti-I’… my ideal otherness… This is not a person, but the direction of my movement”.

My love for you is not an ardent thing,

And I can take or leave your beauty’s lustre:

In you I love past suffering’s memories’ muster,

The misspent youth to which I’d like to cling.

And when, betimes, I look upon your face,

On delving eyes in my preoccupation:

I’m having then a secret conversation,

For you are not my words of passion’s chase.

I’m talking to a love of younger days,

And in your face I’m other’s features seeking,

The lips of one who’s long since finished speaking,

In eyes extinguished flame of other’s gaze.

If one carefully read this poem, written in the fateful 1841 ten years after the passionate love for N. F. Ivanova, then, according to Lotman, it expresses (through love, but not real love; through love, but for another; through love not for her, but for something in the object of love; for something connected with the lover himself) the poet’s love-aspiration for his ideal “I”.

After “happiness soon changed” with Ivanova, one can trace the transformation of Lermontov’s passionate love into “love-aspiration”, starting with attraction to Varvara Lopukhina, expressed in a poem written in 1832:

Not with the proud kind of beauty

She charms the animated youth,

And she doesn’t drag behind her booty —

The crowd of her slaves, confused.

Her waist isn’t one of any goddess,

Her breast does not rise like sea waves,

And nobody calls her gorgeous,

While falling on his knees on earth.

But every movement, every action,

Her features, speeches, smiles — all these

So full of life and inspiration,

So full of otherworldly ease.

Her voice pervades the whole soul,

Like memory of happy days,

And heart is sunk in love and dole,

While being shameful of its zest.

Biographers know that, carried away not by the bright beauty, but by some “original charm” of the seventeen-year-old Varen’ka Lopukhina, student Mikhail Lermontov felt the sincere sharing of his love. It is also known that the relatives of Lopukhina prevented the rapprochement of the lovers, and then three years later, His Majesty the ball, which became an invisible companion of any noticeable love in high society, entered into the matter of chance. A certain Bakhmetiev, retired major, a 37-year-old landlord, who thought of marriage, saw “an undoubted indication from above” that “Varenka Lopukhina hooked her ball scarf on the button of his coat.”

This love has remained with Lermontov forever — «faithful dreams» have preserved that image, «that look full of fire,» and, regretting the bitter fate of his beloved, he prayed for the salvation of her «beautiful soul»:

…I want to hand over the innocent maiden

To the warm intercessor of the cold world.

Surround her with happiness as she worthy of bliss,

Give her companions full of care,

Give her youth and old age peace —

To the innocent heart world of prayer.

Бесплатный фрагмент закончился.

Купите книгу, чтобы продолжить чтение.