Бесплатный фрагмент - It’s capoeira between us

Conversations with capoeiristas. Part 1

Foreword

When I started this book, I had no idea what the result would be. My designs were ambitious — to collect interviews from people who, in their country or region outside of Brazil, influenced the course of capoeira’s history. Some of whom initiated this historic act, some have already become legends in the capoeira world, while others live quietly and do what they love.

Interviews per se, questions and answers, are not so interesting if the context is unknown. It would not be clear to me what questions to ask without context, and for you, dear readers, it would not be such an interesting read. Therefore, I decided to speak only with people:

— I know personally and who share similar vibe with Cordão de Ouro world.

— Who have several years of teaching experience in the country and have an actual capoeira group.

— Who are currently working with capoeira.

I needed this context to know what kinds of questions to ask. For the readers, I have prepared the context of my own life, and a map of my travels and notes about amazing cultures and incredible adventures in the countries where the heroes of this book live and work.

My idea took shape during the course of my work, changed, and evolved until it was finally settled on the pages of my first book. Writing a book is not easy, but writing about the lives of others is an even bigger challenge. I leave it up to you to decide if I have succeeded.

I tend to trust people, sometimes even too much, so I have only checked the words, names and dates that the heroes of this book have mentioned, during my interviews with them, where there were cases of obvious inconsistencies or where there were seeming doubts in the voice of the respondents, to specific questions. Please keep this in mind, when you read the interview, as well as the fact that this book does not claim to be a textbook on the history of capoeira. Nevertheless, I urge critics to share with me their additions and corrections if you find herein questionable information.

“It is capoeira between us” is the main idea of this book. It may well be that among the heroes, or between the reader and the hero, there is nothing that ties us, except capoeira. I approached my heroes with the greatest of respect and an open heart, ready for any answers, trying not to judge them in any way, because these are their stories, their opinions, and they have the right to both have and express them.

I ask you to treat everything that you read here with the same respect, and to not forget that there are varied points of view in the world about a given truth, or a specific situation, and all of them can be correct, even if right now you don’t understand how this could even be possible.

Introduction

What is capoeira? It is a large information field covering all inhabited continents of the Earth. Capoeira is the soul. Or does capoeira itself have a soul? I do not know. But when you connect to it, you feel oneness with everything around you, or at least, with those in your sight. This is such a natural, joyful feeling, one that I both love and treasure.

It is felt when you see a person for the first time, you look into each other’s eyes, shake hands, smile and start a dialogue without even saying a word; a few more strangers nearby are playing instruments, singing, clapping, watching your every move, but you are not scared at all, because you are at home.

Here is another one: you are in another city or country, you are taking the subway to a capoeira event, or you are walking down the street, looking for an entrance to the location, and then someone walks by with a four-strand bracelet on their backpack, and just by viewing that, you immediately become so calm and confident. You do not know the name of this person, but you know that you are family. You come up, smile, ask a question or ask for help, and they answer you, they help you.

Or you are passing through a foreign city, you do not know anyone, so you find a coach’s contact on the Internet; you introduce yourself and speak of your desire to meet and practice capoeira, and they offer you a stay at their home if you have not yet found an overnight stay.

Or when you meet up with a person once a year at seminars, but you have a feeling that during these times you have somehow become closer? This is a wow!

I would call all this a miracle, a utopia, a fairy tale, but no, it all happened to me and to many boys and girls around the world. And why? Because capoeira links us. It is between us when we are close, and when far away, it is always between us, if we choose it to be. Capoeira unites us, connects us to the information field, and we, without noticing, soon begin to add to and enrich this field ourselves.

Who teaches capoeira? What kind of people are they? In different parts of the world, they conduct their work, call themselves capoeiristas, show ginga, kicks and escapes, and explain the culture of exotic Brazil to their students. They were born and raised in different families, they belong to different cultures and social strata. They could have lived their entire lives on different continents, not knowing about each other’s existence! But no, once they drank from the source, they wanted to share their joy with others. And one day a leaflet from one of these people entered my life and landed on my table.

Then there I was, in capoeira. When I came to the first class, I didn’t really understand the world I had entered. But having entered this world, its art has influenced my life path in many ways.

Several times in my life, several persons have encouraged me to write a book about all my adventures, but it always seemed so pointless to me.

Сapoeira, to my surprise, gave meaning and impetus to this idea as well.

It happened in South Korea in 2019, as walked around a lake, in the mountains, early one morning. At that time, I had been practicing capoeira for only 4 years, and I could already speak Portuguese very well. I had already been to Brazil twice, as well as to Israel and many places in Russia.

While walking, I was thinking about all those people who showed capoeira to the world and brought it to different cities and countries. Some of them had already become living legends, while others were still young, but had already managed to leave their “fingerprints” in the history of capoeira.

I became anxious to learn more about them. I had an irresistible desire to talk to them personally, to learn their stories, their motives, in order to have a complete picture of capoeira the world over.

Capoeira has travelled beyond the borders of Brazil; it has fallen into the framework of other cultures, and has taken root in foreign mentalities. How did it happen? How has capoeira changed in these countries? What kinds of people choose capoeira in this or that country? What difficulties do coaches face? What do Brazilian masters think of capoeira being practiced outside of Brazil? These questions ignited my curiosity!

And it was on that morning, in South Korea, that I decided to write about these people and to share my work with the world.

About the Author

My name is Natalia Korelina. My name in capoeira is Curiosa.

I started doing capoeira in August 2015 in Rostov-on-Don, Russia. I was 20 years old. That year I finished my second year at university and decided to quit because I didn’t like the process itself. I started doing capoeira with monitor Brasileiro.

When I came to the first class, I only knew that capoeira was from Brazil and that it was somehow influenced by and resembled fighting and dancing. I came and they showed me ginga and a couple of kicks. They also showed a rhythm on a “drum”. In fact, it was the drum that made me come to the second class.

I did well, I made friends. The group was small: 6—8 people. After 3 months, everyone began to vigorously discuss an event, a master and belts. I had not been encouraged much to participate, no one bothered to explain the whole master and belt concept. And then the gloomiest and most taciturn guy named Tough Guy said to me, with eyes shining, “Be sure to come, it will be very cool, this is motivation for the whole year!”

And I did go. I borrowed money and came to take part in it. There was a master Papa-Leguas and a bunch of strangers from different cities. Nobody in the group, not even my coach, spoke Portuguese. Only I and another guy could speak English, and he translated the class on the first day.

The master was irresistible. Confidence and calmness emanated from him; he knew exactly what he was doing. Then I saw real capoeira for the first time, heard the true voice of our instruments and fell in love with it all. After one class, I plucked up the courage and started talking to him, I no longer remember about what. I think I asked if he lived in England, and he said that he lived in Brazil. Then he asked if I would receive the belt the next day. I was hearing about it for the first time and told him that I had only been training for 3 months, and that I was not ready, but he informed me that everything was fine, and that I could already receive the belt.

When I was leaving the coach caught me and said that I would receive the belt the next day, period.

On my way to the ceremony, the following day, I was reading Wikipedia in order to finally find more about capoeira and how Batizado worked. Yes, no one told me about it, and I actually did not ask.

The master himself gave me the belt. At that seminar, I naively asked him, “Are you the only master who travels like this, or are there many of you in the world?”

If only I knew then how many wonderful capoeira masters there were in this world!

Soon regular classes were not enough for me. In the first year, I went 3 times to Krasnodar, once to Moscow and St. Petersburg, and also spent a month in Israel, where I miraculously got to an event with Grande Mestre Suassuna and Mestre Ivan.

During that year, I learned that I was training in the group called Cordāo de Ouro, and that this large and friendly family, which existed the world over, was waiting for me with open arms. Then, I have met almost all the YouTube legends. It got to the point where Mestre Cueca said that he was seeing me more often than his mother, and Suassuna kissed me on both cheeks and said that I was beautiful. I was happy. But I had plans. I was going to work on a cruise ship. I was supposed to get a second belt on the eve of my departure, but I learned with bitterness that the seminar had been postponed and I had to leave without the new belt.

I left for 7 months, trying in vain to keep practicing on my own. I even managed to take time off from work once and train with a group in Miami. And then I decided to catch up on lost time in Brazil. So, having seen my master only once, I wrote to him and said that I wanted to come and train with him. I didn’t even know that receiving guests was a common practice for him.

After a short visit home, I hit the road again. I stopped over in Rio de Janeiro for a little rest and spent some time at a local school, learning Portuguese. Following this, I bought a ticket to the small town of Patos de Minas, where Papa-Leguas lived with his family.

He met me at the bus station at 5 am. I was embarrassed, because he is a master! I was supposed to stay with his student, but she had left for 2 days, and the master offered me a stay at his house until she returned. I met his wife and children; it was like in a dream. I was at my master’s house! What an honor! What a delight! But despite getting close to him and his family, he is still like a rock star to me.

And so, the training routine began; I got acquainted with his instructors and the history of capoeira in Patos de Minas. Traces of this story are scattered all over the world: Mestre Chicote, Mestre Parente, Mestre Piolho and, of course, Mestre Papa-Leguas — they all once trained together, started together, and now live in Europe.

On that trip, I also travelled to the event of world significance — Dia de Ouro, where golden threads appeared in the masters’ belts. And this journey ended at Mestre Suassuna’s home, where I met groups from Russia, South Africa, Miami and other countries at the same time. The geography of our group is vast, but I noticed one trend — all stories lead to Brazil and Israel.

Here, I propose to my readers to go on a trip and find out how capoeira began and is being practiced in different countries. I’ll start with the country where I got the idea to write a book — South Korea.

South Korea

It is our first stop on this capoeira journey and the place that inspired me to write.

South Korea has become a very special place for me. I came here to patch holes in the budget and lick the mental wounds, so to speak. Well. Both goals were achieved. I left Korea full of energy, ideas and love for capoeira.

Korea is a small country with beautiful nature and a developed economy. Technological and economic growth has occurred so quickly here that people and local traditions have not had time to fully adapt. For example, they monitor the waste recycling and protect nature at the governmental level, but at the same time middle-aged people throw garbage out of car windows. By the way, there are a lot of cars here, and all are quite expensive. At the same time, drivers in the provinces do not stop at a red light, drive without a license, and generally don’t regard traffic rules.

Koreans have a curious way of showing respect to “age”. Even if the age difference is one year. This is reflected in the language as well: they use different “you” for addressing a person who is younger than they are and another for a person who is older than they are. This reaches the point of absurdity — I have witnessed more than once when younger friends unquestioningly endured the idiotic antics of older ones. Without going into details, I will say that this does not fit into the modern European mentality, to which I belong.

But this is all happenings in the provinces. Young people flock to Seoul, worship idols (Korea’s ideal pop stars), undergo plastic surgery, speak English, travel, and increasingly protest the archaic traditions of Korean culture. Koreans who have at one point or another lived abroad, stand out a lot. They have much more inner freedom, they look more consciously at everything that is happening in their country. They understand that the Korean mentality puts a lot of labels on people, and this is not always correct.

My conclusions about Korea are limited by my observations, conversations with locals, articles from Quora and videos from YouTube. I am generalizing since you can find any type of mentality even within the same culture. I lived in a province where most of the locals spoke very poor English, so it was difficult to understand what was going on in their minds. Take into account what I’ve said above but do not form any stereotypes.

What about capoeira in South Korea?

While in Russia, I tried to find capoeira in Korea on Instagram using hashtags — I couldn’t find anyone but Zumbi. I looked in Yandex and found the Zumbi’s webpage again. Well, I thought, he must be the only one then. And capoeira, it seems, existed only in Seoul.

I worked far from Seoul and trained by myself in the park for 2 months. I wrote to Zumbi and informed him that I wanted to meet, chat and practice capoeira with him on my last day (and my only day off) in Korea. I had a flight in the evening, and Zumbi’s class was early in the morning, so I hit the road, slept for an hour and a half on the bus, and with drooping eyes came to his class. After that experience, my body had gone into shock. It had already been heavy after a sleepless night and I had rubbed my feet to calluses. I could barely walk after that class, as Zumbi is a maniac. Honestly, if he could, he would literally train all day long!

After the class, we went to have lunch and met Zumbi’s student. I barely remember conversations we had since my head was really foggy. But, having been on a first visit to Korea, I decided to come to Korea again and become better acquainted with the persons that I interacted with. So, on my second visit to Korea, I went to Seoul 3 times to get to know the Zumbi’s group. I met his student, who replaces him in classes when he is away, — graduada Formiginha.I also met his student from Brazil: in fact, this guy began to practice capoeira in England, when he moved there as a child, and continued with Zumbi, after moving to Seoul. I also met a student from the United States with Brazilian roots who teaches English in Korea.

It turned out that I had met one of Zumbi’s students even before I met him. This happened when I came to Brazil to train with Mestre Papa-Leguas in 2017. This girl used to live and study in Seoul, and now she lives in Brazil. It’s a small world, isn’t it?

Are there any other capoeira groups in Korea?

Yes, Some of Zumbi’s former students had split off and continued to work directly with Mestre Chicote. Unfortunately, I didn’t manage to meet with any of them during my time in Korea.

I managed to find 3 CDO groups in Korea. I have also heard of Capoeira Angola and Abada. All groups, judging by the photos, are quite small and do not hold large events.

In my personal experience, most Koreans do not know how to relax and have fun in a healthy way. Constantly competing for jobs, they worry too much about their social image, and Koreans simply don’t have the time and energy to have a real hobby, let alone devote themselves to capoeira and start teaching with a yellow belt.

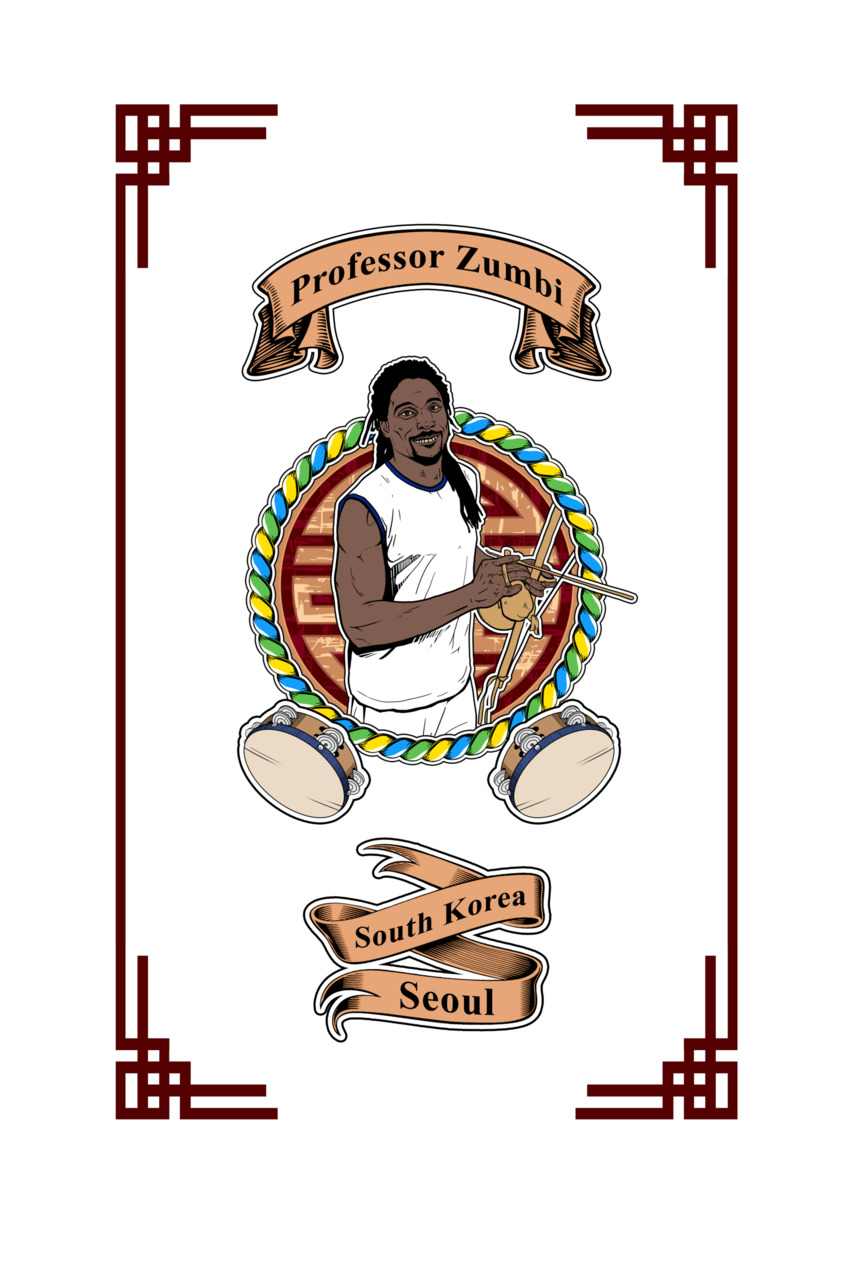

Professor Zumbi — Seoul, South Korea

***

Zumbi is an amazing person who is in love with capoeira. He was the first representative of the CDO school in Korea. He breathes such confidence that it seems that he never doubts that he will achieve everything he wants.

Life is unpredictable and full of surprises, which is why, while in Korea, I interviewed Zumbi on Skype, and not in person. Zumbi was in the United States at that time. If I’m not mistaken, the difference between us was about 12 hours or even more, so I had to get up early for the conversation while for Zumbi it was the evening of the previous day.

Conversation with Professor Zumbi.

Curiosa: Tell me about your background: Where were you born? Where and when did you start practicing capoeira?

Zumbi: I was born and grew up in Jamaica. In 2000, I moved to the USA at the age of 23 where almost immediately I started to practice capoeira. I started in Berkley, California with Mestre Marcelo Caveirinha in the capoeira Mandinga group. At that time, it wasn’t so popular to use the name of Cordão de Ouro, so basically I started with CDO masters in a group with a different name. Capoeira became my passion and was my motivation to get good grades at university. I would allow myself 4 hours a day to practice capoeira but only if I got excellent grades!

In 2003, I started to train with Mestre Chicote in Vallejo, Oakland, and SF. These times were hard ones because Chicote was giving classes at different hours and in different locations, still I tried to go to all of them even if they were far and ended late.

Curiosa: When and how did you start to teach capoeira? Was it easy? Did it come naturally?

Zumbi: In 2005, I started to teach capoeira with the yellow belt. I didn’t really make any income from teaching, but I saw it rather as a hobby that would allow me to organize my own workouts during the week. So, I would give classes at the same place and hour to my students from Mondays to Thursdays and trained with the big group from Fridays to Sundays.

As to whether it was easy, discipline and goal setting have always been important for me. I enjoyed preparing for every class, explaining capoeira to others and mastering my own skills through teaching and for me teaching came easily; it is a part of learning.

Curiosa: Who was your greatest inspiration in the practicing of capoeira?

Zumbi: Among the people who inspired me and influenced my capoeira the most are the 2 first American masters: Beringela and Xangô. They are geniuses in capoeira because they managed to excel in all areas of capoeira and to understand all cultural and traditional aspects of it without actually living in Brazil.

Curiosa: Why and when did you move to South Korea? What was the situation with capoeira in Seoul at that time? What is the situation now?

Zumbi: In 2009, a Korean company offered me a full-time job, which was too good to refuse, in Korea. So, I moved to Seoul and immediately started to search for capoeira classes. I found a group called Filhos de Bahia. The leader of the group was Mestre Nei Boa Morte. Their teacher’s name was Alegria, but he had temporarily stopped teaching and his wife was giving classes instead. I didn’t enjoy going to their classes and was training alone in a gym. The same year, a student of Alegria started a Muzenza group. I was visiting their rodas and helped them with their first Batizado.

Soon after, I started my own group and right now I’m not getting on well with any other capoeira teachers in Korea. Most of these Korean teachers never left Korea and haven’t been to Brazil, so we always have disagreements on how things should be done.

Curiosa: What did you do to form your first group?

Zumbi: I came to Korea with a yellow/blue belt, and I was an estagiario.

Curiosa: I know it as a monitor belt.

Zumbi: In the class, if you have yellow/blue belt, your teacher tells you what to do and you show that to the class, then you become a monitor. However, if you don’t have a master who teaches you, or like in my case, you’re the only representative of your group in the whole country, you are called an estagiario.

So, I was working out alone in a gym every day. One girl kept looking at me and finally I offered to teach her. I said, “If you want to learn, you should come every day at 6 am and be committed.” So that’s what she did. Soon she started to come with her best friend. We would have discussions and drinks after the classes until I eventually formed a capoeira club.

I got lucky. My employer sponsored my club with $800 per month that I spent it mostly on musical instruments. Soon there wasn’t enough space for everybody to train. We rented an acrobatic studio, which cost $2000/month, for free. Again, it happened because the owners of the studio wanted to have good partnership with my employer. There were fifty students by then.

Most of these students were highly educated Korean boys and girls between 22 and 32 years old. They all spoke English, so it was easy for me to give classes, although I had been learning Korean.

Curiosa: How quickly did you learn Korean language?

Zumbi: It took me four months to learn 40% of Korean language that I now speak. The rest took me more than three years.

Curiosa: What are the major milestones of your work with capoeira in Korea? Were there any dramatic or difficult moments that caused you to consider giving it up?

Zumbi: This big group existed for one year. Many people already knew about me and my club but some of them couldn’t participate because they were affiliated with the competitors of my employer.

That was one of the reasons why I decided to form a real group and to start giving paid classes in a dance studio. It happened in 2012. Believe it or not, but in that studio, I had just 6 people. I think most people just didn’t take it seriously and gave up capoeira because they had to pay for the classes.

Curiosa: How do Koreans see capoeira? Why do they choose capoeira?

Zumbi: Koreans are a very busy nation where the people are highly competitive in studies and in the work place. They are always busy with crazy hours at work or with their families. Korean people have many sports to choose from, but they don’t really need a hobby. Some find their passion and follow it. But majority just try things out and drop them for things of a higher priority such as work or family.

So, for me, it was a time to learn this bitter truth, but I also had mainly foreign students who naturally wanted to have a hobby and a community to socialize with. And yes, they were ready to pay for this. So, I was back to over fifty students again.

I worked hard to attract people at that time. I made many street rodas and distributed some flyers. And from a small number of foreign students, my group grew to fifty-five people, half of whom were Koreans. Those were the best years for the group: I held 10 events with many masters including Chicote, Acordeon, Tico, Cobra Mansa, Kibe and many other. At that time, I had two students with yellow belts and one monitor in my group.

But, in around 2015, there was a major change when I had to leave often to see my sick father. I wanted to be quiet at that time and stopped going to the parties. The way I taught capoeira changed as well. I focused more on capoeira wellness rather than on fighting aspect. I introduced meditation sessions before the capoeira classes. They were optional and free. Students started to leave. I think only those who genuinely liked me and capoeira stayed with me.

In 2017, I made a decision to close the studio. It was a sad time.

I found a new passion though. This was my work with cryptocurrencies that I still have as my main occupation today.

But as for the students who remained in my group, we moved from place to place every 2—3 months.

Curiosa: Are there any the legal requirements for teaching capoeira in Korea? Did you need to provide any documents in order to give classes?

Zumbi: As for the legal requirements are concerned, I formed a legal company. To be a capoeira teacher in Korea, you don’t have to have special education.

Curiosa: What are the main competitors to capoeira in Korea?

Zumbi: I stopped thinking about competition between capoeira and other sports. You just have to inform people about capoeira and let them decide whether they want it in their lives.

Curiosa: You don’t have a master next to you anymore. How do you stay motivated and develop your capoeira?

Zumbi: I don’t really need anybody to motivate me. I am developing my capoeira through teaching.

Chicote put no limits on my creativity as long as the result of my teaching methods were good. However, when the master was around, it wasn’t easy. He saw and mentioned all the mistakes.

Nowadays, I am working with Mestre Xangô. Xangô comes to my events every year.

We haven’t set the date for this year yet because my students haven’t completed their curriculum yet.

Curiosa: Do you students have a curriculum?

Zumbi: Yes. I’m not just teaching capoeira — I am teaching life skills. If they can’t set a goal and commit to achieving it in capoeira, they won’t be able to do it in life either.

I require all my students to start giving classes with yellow belt. I only give them a goal, the way to achieve it, they choose themselves.

Curiosa: How do you see the future of capoeira in Korea? Are you planning to stay in Korea for the rest of your life?

Zumbi: I plan to stay in Korea for the foreseeable future as well as expand and grow my group again. I want to teach capoeira in the USA and Jamaica as well.

I received the professor’s belt in 2015 from Mestre Acordeon in Paris and I am completely satisfied with it. I don’t really want to get the next belt because of the responsibility that comes with it.

Curiosa: What place does capoeira take in your professional and personal life?

Zumbi: From 2000 to 2011, capoeira was my first priority. But, as of 2012, the first place has gone to meditation. My priority shows in my commitment.

My everyday schedule shows it in the best way: at 6am I start meditation, then at 7am I train capoeira, and then go to work. Relationships and other stuff come after. Capoeira is a big hot fire. And you need to know how to manage it. Capoeira enhances one’s life but one should be careful not to let capoeira become a burden.

Interesting facts

— Zumbi doesn’t teach kids. He says he is very much into the discipline and doesn’t have enough flexibility to have kids’ groups.

— He got his apelido because he was “big, black and scary”.

— He has a Brazilian student. Yes, a Jamaican is teaching capoeira to a Brazilian guy in South Korea. (It made me smile).

China

Welcome to our second stop and the most difficult journey in my life.

China is not an easy country. There are too many people here, and this is not just statistics. Shanghai airport and railway station are overcrowded. Just to get into a taxi, I had to wait in line for 40 minutes. Roads, overpasses and bridges are multi-level and multi-lane. There are separate lanes and even tunnels for scooters and bicycles, because there are too many of them as well. The traffic is confusing, chaotic. Everyone runs and drives, and it seems that if you stop even for a second, you will be run over or trampled. Prices range from ridiculous to sky-high. And many foreigners believe that all products in China are counterfeit. Kinder and Nutella are not tasty here, for example.

There are too many McDonald’s and Starbucks cafes here for a country that has blocked almost all major American sites and apps such as WhatsApp, Instagram, Facebook, and YouTube. When I say they are blocked, I mean you literally can’t download or use them unless you have a good VPN and some luck! Imagine this. I was devastated because I couldn’t talk to my family for almost two months.

There are also many foreigners here. Everyone has to learn Chinese, because there is no other way to survive. The Chinese do not speak English in taxis, shops or cafes. Catching free Wi-Fi is almost impossible, without a local SIM card and VPN it will be difficult to use the usual Internet. All life, communication, payment for absolutely everything: food delivery, taxi and even government services are concentrated in the WeChat application. If you don’t have this app — consider that you do not exist in China either. Even homeless people here accept money on WeChat!

And what about capoeira? The history of capoeira in China began in Italy. Yes, in Italy. And I will have to learn that history when I go to Italy, because the person who brought capoeira to Shanghai, and then spread it to several more cities, returned to Italy years ago.

Nonetheless, I attended the local group of Capoeira Mandinga in Shanghai and was pleasantly surprised by the number of students there. There were about 20 of us. The teacher’s name is Nico or Instrutor Virtual, he is originally from France and was giving the classes in English. There were 2 more girls from other countries, the rest of the students were Chinese. The level of playing in the roda was very impressive — a good base was visible.

Notes from China

After the Saturday roda in Shanghai, I went to the city of Shenzhen located on the border with Hong Kong. This city is considered the capital of watchmaking in China. I found out about this little detail by translating an article about the manufacture of replica watches in China for my work — a funny coincidence. I don’t often work on texts that are so directly connected to my life.

So, I came to work as an English teacher in an early learning center — where there were no children yet — it did make my life a lot easier. I would create lessons and use a lot of ideas from capoeira classes, which I conducted, together with my teacher, Professor Biruta in Rostov-on-Don. I chopped a bamboo branch with a kitchen knife, hanging from the second floor, repaired the printer (in Chinese, yeah), painted a photo corner for the Mid-Autumn Festival and tried to put my colleagues on the right path in terms of healthy eating (well, you can’t just eat fried, spicy and salty stuff every day, even if it’s vegetables). For some reason I showed 2-year-old children a presentation about Vietnam, although they don’t even understand what a country is. There, I also had to learn to read fairy tales in English beautifully and expressively while recording all of them on video.

The city was very green and hot. There was also high humidity and tropical showers, Tesla cars passed every 5—10 minutes. Every now and then I met foreigners. Unlike South Korea, where all foreigners live mainly in Seoul, in China they can be found almost everywhere.

The guys from Shanghai gave me some contacts of capoeiristas in Shenzhen. It was already great luck that capoeira existed there.

The first person I wrote to was a guy named Matthew from France, who previously worked with the Capoeira Ginga Nago group, and at the time of my stay in Shenzhen — in the Capoeira Brasil group under the direction of Mestre Chumbinho. The master was originally from Australia and at that time lived in Hong Kong. And yes, every Sunday he came to another city, and actually to another country, to give a capoeira class.

In my first week in China, three things happened:

— I found two more capoeiristas: a guy from Portugal from the Rabo de Arraia group named Tiago and his girlfriend from Belgium from the Beijing branch of the Mandinga group named Yuni. Tiago taught free classes in the university lobby twice a week. I met them on the Friday.

— I was invited to a Brazilian party on Saturday night and was added to the city capoeira chat where this very party was discussed. The master asked who was going there, and I was the first to answer. Furthermore, the first six people who volunteered to perform could receive tickets to the buffet. Brazilian food. Any. Even churrasco. For free. I was ready, but nobody had known me yet, so I was not included in the list.

— On Sunday, I went to train with Mestre Chumbinho. Capoeira Brasil are classic representatives of the Regional style. Well, there were a lot of kicks, trips and a kind of “the last survivor” — who will last the longest in the game. I was participating in the last round with one guy, but when the game became completely monotonous and ugly, and my head was throbbing and was about to explode from overheating, I gave up.

And now, everything in order.

Tiago and Yuni are wonderful people and capoeiristas. They met in Spain when Yuni attended a local capoeira group event she had never heard of before. Tiago was there. Well, so it started. He visited her in Belgium, then in China, where she had been working at the university for many years. Then he came to China and stayed.

When I arrived, Tiago had been in the city for less than six months, but he had already worked in a sports club and taught capoeira to kids, and was looking for a studio for an adult group. His classes were amazing, and my only complaint was, “Why is the class is over already? I want more!”

From conversations with Tiago, I learned a few things about capoeira in Portugal, about European Portuguese and decided to go there one day.

In Tiago’s training, I met several more students from other countries and groups. It was very interesting. Each person had their own history; the group was a mixture of cultures and spoke several foreign languages, ahh. I am having goosebumps as I write this. It was incredible to touch other worlds, personalities and cultures through capoeira, and still feel at home.

The Brazilian party.

Well, what can you tell us about a party? — you would ask. Everybody performs, everybody goes to parties. And what will you say to six people from five different groups and six different countries who are gathered for the performance? And we put on a show together as if we had known each other for ages, like old friends.

I had never seen anything like this. Against this background of experiencing unity through capoeira, even the delicious Brazilian food lost its importance. Mestre Chumbinho hosted the entire show, sang and played the berimbau. And we, without any preparation, simply followed his instructions. Everything went like clockwork. People clapped, groaned and admired. There were even two volunteers who learned a couple of movements and amused the audience with their impromptu fight.

Initially, I was not on the list of performers, but they lacked one person, and I had brought white pants and a white T-shirt with the CDO logo with me. Just in case, you know. All participants in some miraculous way brought only white T-shirts. Everyone had white pants with their school logo:

• Mestre Chumbinho — Capoeira Brasil — Australia

• Taf — Capoeira Brasil — UK

• Matthieu — Capoeira Ginga Nago — France

• Tiago — Rabo de Arraia — Portugal

• Yuni — Capoeira Mandinga — Belgium

• I (Curiosa) — Cordão de Ouro — Russia

Moments like these are worth living for!

It all ended with sincere conversations about where everyone was from, which school they represented and how they ended up in China.

Training in the Capoeira Brasil Group.

Late, but I arrived for the class. The master conducts training with humor, but makes you sweat with a lot of repetitions. There was only one Chinese student among us. There was also another Russian girl and all the same faces: Taf and Matthew.

At that training session, I felt out of place as never before. This was not my capoeira. The very approach to training was completely different. Although I must admit that such training was necessary for me on a regular basis in order to learn to play quickly and strongly at a new level.

Conversation with Instrutor Virtual.

Let's go back to Shanghai and talk to Nico a bit.

Curiosa: What is the state of capoeira in China?

Nico: Officially, Capoeira Mandinga Shanghai was established in 2008, then it came to Beijing and then to Taiwan. Then a student from Russia who started with me moved to Hangzhou (a city one hour away from Shanghai). There were already some people who were doing capoeira there, but it was a very small group, which wasn’t really affiliated with anyone. After some time, they also wanted to join the group of capoeira Mandinga. There’s also one guy in Hefei who has 3 or 4 students already. One girl from Hangzhou also moved to a city close to the border with Thailand, she already has around ten students. So, there are three major cities and these two little groups. In Shanghai, there are two groups of capoeira Mandinga now. The person who moved to Hangzhou came back and started his own group. Now the two groups meet for a Saturday open rodas once a month.

The other teacher’s name is Alex, Chupateta. His group has about 5 to 15 people, whereas my group has 6 to 25 students depending on the day of the week. Students of the Capoeira Brasil group also come to the Saturday open rodas.

Curiosa: Many students left Shanghai and started groups in many other cities. Were all these students advanced enough to start teaching adults on their own?

Nico: When Diego came to Shanghai in 2005, he had only three years in capoeira, he didn’t find any capoeira group there and asked his master in Italy if he could start teaching capoeira. His master said that he could not and that his only option was to stop doing capoeira.

Diego didn’t listen to his master and started to teach. Then they invited Mestre Marcelo and became Capoeira Mandinga. So, when he started, he was just a yellow belt and then for many years he had the highest level in China. But then Capoeira Brasil came and people there had a higher level. I started to teach with dark green belt. Once in a while I would teach what I knew.

Then when you go to another city and there’s no capoeira, so what do you do? You’re like: hello, I have three years in capoeira, do you want to try? And it starts like that.»

Curiosa: What belts do your students have?

Nico: The highest level in my group is yellow belt. Half of the people in my group started with Diego and all the beginners started with me.

There is another guy in Shanghai that is even more advanced than me. He is from the USA and used to be part of Mandinga group but decided to leave. He is not affiliated with any group now. He teaches capoeira in a gym and supports all the rodas.

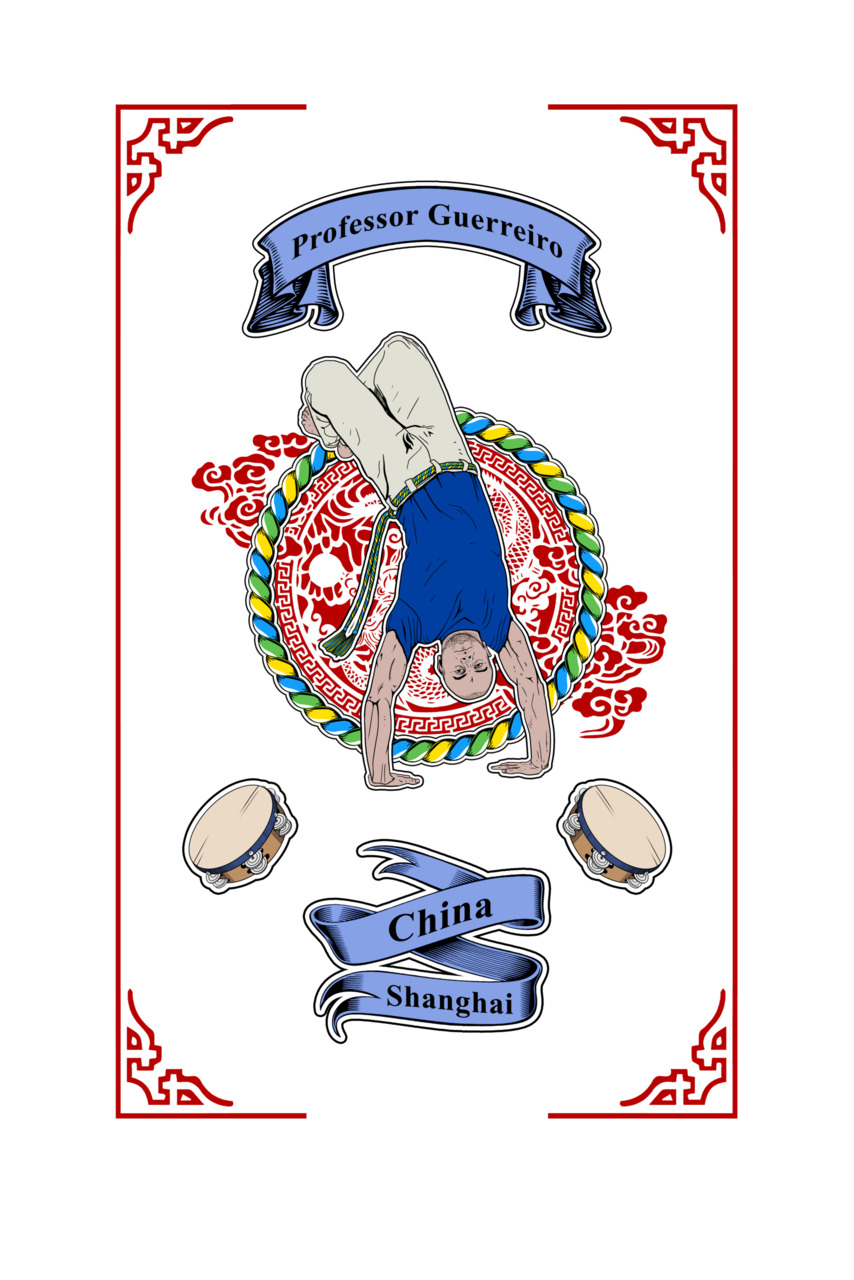

Professor Guerreiro — Shanghai, China

***

I have already said that Diego returned to Italy. He now lives in Milan with his wife Elisa (Instrutora Princesa). I met her at a seminar in Milan in October 2019. There were several people with Capoeira Mandinga logos on their pants. I didn’t know anyone from their group in Italy at all, so I went up to say hello and told them of my desire to attend Diego’s classes. Elisa, as it turned out, knew about my existence. I told her about my project and that I wanted to meet Diego and interview him. On the same date, Diego himself was at a seminar in Shanghai with his group.

I must say that Diego’s move to Italy was in many ways a decisive factor in my decision to travel to Italy. I was eager to go there almost every year, but something always hindered this desire. I had heard so much about this country that it seemed that I had already visited there. Then I realized that without a visit to Diego, I would not be able to finish the chapter on capoeira in China. Moreover, other very talented capoeiristas live there, so I would able to talk to them as well.

At last, the long-awaited meeting with Diego took place. I remember it was a Tuesday evening, I walked for a very long time along the dark, cool streets of Milan, cursing at the endless cobblestones, where my small suitcase was constantly getting stuck. Not without difficulty, I found the entrance to the gym, I didn’t see any familiar faces. They let me into the locker room but then I did not understand where to go, and no one understood me. But when we did finally found each other, I was very surprised how pleasant and humble Diego was.

Diego turned out to be a very jovial, pleasant, open and down-to-Earth person. I would never have suspected that behind such a face there was such a force and such a story. When I understood what work he had done both in China and in Italy, what success he has achieved in capoeira, I wanted to give him a standing ovation and shout “bravo!”.

Conversation with Diego

At the first class on Tuesday, I sat in a corner and just watched the class — it seems that I had a fever back then as my head was splitting. Luckily, we managed to make an appointment to meet early before the next class on Thursday for an interview.

And so, it happened. We met in the lobby of the sports center before training. Diego was with his wife, Elisa, who added comments to some of his answers. Diego was so quick and clear in answering the questions, it was as if he had already been rehearsing the answers.

Sit back and enjoy this incredible dialogue.

Curiosa: Where are you from? When did you start capoeira? What did you do before capoeira?

Diego: I am from Italy, Naples to be specific. I started capoeira in 2001. Before that, I did judo for 4 years, taking part in competitions. Then I received a shoulder injury and I decided to start another sport. I was studying in university back then, so I was 19 or 20 years old. My friend suggested that I try capoeira, so we went together, and started to train with a teacher, his name is Tatu from the Balanço do Mar. It is the current name of the group in Napoli. I trained there for almost 3 years. Then I spent 6 months in Beijing in 2004, but I didn’t do any capoeira there. Then I came back to Italy, to Napoli. And in September 2005, I moved to Shanghai.

Curiosa: Why Shanghai? Why China?

Diego: I studied international relations along with Chinese language at university, so I went to China to study. And in 2005 I went to Shanghai because I won a scholarship from the Italian Minister of Foreign Affairs and they sent me to Shanghai. When I came, I looked for capoeira everywhere. I was going to Brazilian restaurants and then a Brazilian guy told me there was a guy in a park in Shanghai doing capoeira on weekends. So, I went there, I found the guy. He was there with a bunch of people. And actually, he was leaving and he asked me and another French guy to continue with the classes. So, basically it was just a group of people, they were training on Saturdays and on Sundays, once a week when there was no rain. And we continued to teach.

One of the first guys, who is Japanese, met his wife while doing capoeira, they eventually had a child, and we actually went to their wedding in Japan; I did the best man’s speech. It was quite an experience to be a best man at a traditional Japanese wedding.

Back in Shanghai, I was teaching only super basic stuff because my teacher was teaching only very basic stuff. So, I was doing very simple capoeira, and we were hanging out after the class; the vibe was good. When the winter came, an English fellow proposed to use the facility that was in his compound. So, we went there and started to train once a week sharing the rent. We were having easy classes for one hour, then we would go outside to have drinks. This kind of vibe brought a lot of people. Let’s say, there were 20 people training, all expats, foreigners from all over the world. It was really fun.

But the capoeira was… let’s say — bad; the technical part of capoeira that is.

Curiosa: Did you do any music back then?

Diego: Yes, we did music. I was doing my best. I learned there by myself how to actually play berimbau. I knew basic songs, but it was a challenge. I had to lead the rodas, so for me, music was always twinned with capoeira. One Italian guy was really advanced in the movements, but, for him capoeira was without music, so we never really got in touch with him. I wanted him for his movements, I wanted him to come to classes but then it never happened actually — he was just a performer, not a capoeirista.

So, after that, I came back to Italy for holidays, it was in 2007, and the mestre of the group, Mestre Alemão, was teaching in Genoa, but he was giving a workshop in Napoli. I was paying and supporting the class and at the end of the workshop, he pointed at me and said, “I heard that you are teaching and doing capoeira there, but that there is no mestre; I don’t think that’s a good idea. You shouldn’t teach what you learn here, you shouldn’t train capoeira without a mestre.”

So basically, I was kicked out of the group because according to him I was supposed to quit capoeira from the beginning because there was no mestre there. So that was the end of the story with that group.

Then at the end of 2007, I met Mestre Marcelo. He contacted me by email. He said that he was going to Japan, he had found their capoeira group in Shanghai while searching the Internet and could teach a workshop there.

Curiosa: But how did he find you?

Diego: He found us on the Internet, we had a group there, with an email address on the page. He was curious. He was in Asia and wanted to see what’s going on in Asia. There was no Facebook at that time, there was no social media. A I had no idea who he was. First, because my capoeira education was really low. Second, there was not much Internet use at that time. So, I was really scared about inviting a Brazilian guy to Shanghai and paying for airplane tickets — it was something that I have never thought about. But eventually we came to an agreement: I trusted him, he trusted me. So, we bought his tickets to Shanghai and he gave a workshop. We were roughly 20 to 25 people; we were friends basically. So, he taught the workshop and we were all very impressed. I had never before witnessed such beautiful capoeira. He was in his 40s and he seems to have been in the best capoeira form of his life. Whatever movement he was doing, from the ginga to the macaco, it was amazing, it was something I had never seen, for my capoeira had been limited to what I had learned in Napoli.

Curiosa: What kind of capoeira was it?

Diego: It was more regional, I believe. Keeping in mind that my style was super bad. I am still fighting to get rid of it to this day.

So, it was really a big revelation for us, we were inspired by him. Not only that, we were also inspired by his philosophy, his idea, and his vision of capoeira. The thought came to my mind, “Ok, this is what I have been looking for in capoeira.” Maybe I felt there was more to capoeira, but I never knew because I was in the different world. So, at the end of the weekend, we talked and we actually had this connection; he agreed to have us as part of his group, Mandinga, and to support us. And this support was not just lip service because, in March 2008, four months after the workshop, he sent to Shanghai a contra-mestre, Mexican Contra-Mestre Cipó. And he taught classes every day for 3 months. He was really good and really tough. The group was halved because classes were too tough but for the people who stayed, they really learned capoeira, gained an understanding of Capoeira Mandinga, and came to understand what it means to train capoeira. It was like walking through the fire, we were really exposed to the top notch stuff. After these 3 months, we invited two more teachers of Mestre Marcelo. It was a couple: an American contra-mestra and a Brazilian professor. They were a married couple and they came to Shanghai for 3 more months from July to September. They helped us organize our first Batizado. which we had in September; they also taught very technical capoeira, very Mandinga/Cordāo de Ouro style. So, having that full immersion with them turned out to be very vital and life changing.

Curiosa: And what belt did you get during that Batizado?

Diego: Yellow belt. It was my first belt ever because my old group also never had a Batizado at that time, so I never had any belt.

Curiosa: How long did it take you to receive that belt and why?

Diego: After 7 years, but I wouldn’t count all 7 years because for me, the first three years were wasted and when I was in Shanghai teaching, I was learning some bad berimbau technique and in capoeira I was reviewing some kicks. I was just involved in some capoeira moving but still keeping it very basic. So, as you can see, that year was very important for me.

Then we invited other teachers from Mandinga school during the following years. But for me, those 6 months were the key. I was taking daily notes from all the classes, so I had material for years. This is what I have been doing after, rearranging something of course.

Curiosa: Why did you decide to stay in Shanghai?

Diego: I found an internship, and in 2007 I was contracted by a bank. I was working there and teaching capoeira in the evenings.

Curiosa: What are the major milestones in the development of your group in Shanghai?

Diego: The first Batizado was of course an important milestone. Then, I don’t remember the exact year, one female student, named Morena, who had been training with me almost from the beginning, moved to Beijing. I think it was in 2011 or 2012.

There was also a group of people that were always present at our events, they were struggling with their training and they wanted to become a part of Mandinga, but we never got organized.

She went there and she took over, so she started to teach classes and they organized a group and they grew a lot, and it became a Mandinga group.

Another milestone was when Alex Chupateta moved to Hangzhou and started a group there. It was very funny. The first time he came to my class in 2008, he was speaking Chinese; he couldn’t speak a word in English and his only language besides Russian was Chinese. I was able to speak Chinese, so we were communicating in Chinese in the beginning. He was already in love with capoeira; he was super committed, and eventually he learned English and Portuguese. And when he moved to Hangzhou he started to teach there. Now he is back to Shanghai, but the Hangzhou group is still there.

The Beijing group is still functional, but Morena is now teaching in Iceland because her husband is from Iceland.

And then another important milestone for the Mandinga happened when one Taiwanese capoeirista came to my class. I think it was in 2009 or 2010, after class he indicated that he liked the energy and the vibe of that class; he said there were a few people in Taiwan and they had some issues with other groups there, as they didn’t like their styles and so he wanted to know about our group.

I told him it would be OK for him to come to our Batizado, so that he could speak with Mestre Marcelo. Three of them came to our Batizado, that would be the second or the third one, and they asked to join the group. Basically, we started to support them, so they could become a part of Mandinga group. I remember my first workshop there was in 2011, there were 9 of them in the class, all super beginners. I then left China in 2015, and when I returned in August of the same year, there were like 70 students; the capoeira level had risen dramatically. What they are doing there is an amazing job. People from all over Asia go to their events because they are super fun. They have nice vibe, good energy and most importantly, they are super good at capoeira.

They are also very into the design and marketing of gadgets and other paraphernalia, but their excellence in capoeira is undoubtedly their drawing card. They are really committed, I saw them in the beginning and every time I see them now, I see that they’ve grown and have done an amazing job.

Yet another milestone was when I became an instructor in 2012 and then I became professor in 2015; it was my Formatura. Personally, I trained with Ido Portal, I invited him twice to Shanghai in 2011.

Curiosa: For a workshop?

Diego: Yes, he wasn’t famous yet, but he was known in the capoeira community. He gave a workshop in March and September of 2011. Let’s just say that from those workshops, we could see that he was at a different level.

He is a very interesting guy and I became his student, I did online coaching sessions and many workshops with him, and within 3 years he had helped me to completely alter my body, change my views about certain things and taught me how to protect the body. Further technical knowledge was also imparted by him to me.

Curiosa: When you came to China, what was the situation with capoeira and how has it changed?

Diego: When I moved to China in 2005, capoeira didn’t exist, nobody knew except for some Brazilian waiters that I met in some Brazilian restaurants. Pretty much no one knew about capoeira there. The only people who knew were those 10 people in the park.

What happened next. By 2008 or was it 2009, I don’t quite recall, we had 2 Chinese students. I’m not sure how they found out about capoeira, they were a husband and wife. They were our first Chinese students and they are still training with us today. She has also gotten her yellow belt now, after 10 years. 10 years I know seems like a long time, but we are very conservative.

But then in 2010, at Shanghai Expo, through some friends, we were given the opportunity to do 2 or 3 performances in the Brazilian Pavilion. Thus, capoeira was being advertised everywhere: in subways, in magazines etc. And that is how the Chinese people started to look at this Brazilian thing: a dance, a martial art, whatever. So, after 2010 we started to have more Chinese.

Curiosa: Were there mainly expats in your group?

Diego: We had only expats until 2009; after, we initially had 2 Chinese, now we have more Chinese and foreigners.

Curiosa: How did you manage with the language?

Diego: I went to Beijing for 6 months and I learned it there.

Curiosa: In what language did you offer your training?

Diego: At first, in English. I was giving classes in English most of the time until the majority of the class became Chinese, then I mainly used the Chinese language.

Curiosa: So how did you end up teaching capoeira back in Italy?

Diego: In 2015, I moved back to Italy, to Milan. I trained with Nadav for 6 months and then in September 2016 a couple students who had trained with me in Shanghai moved to Milan.

These students comprised of one Italian guy who was originally from Milan, he had been taking capoeira classes here with a group, but when he moved to Shanghai for a year, he ended up training with me.

The group here was closed and when he moved back, he said I should teach capoeira again because he didn’t want to go back to that group and he wanted to train “my” capoeira.

So, with me, my wife, him and his girlfriend at that time, there were four of us already, so I agreed to give it a try. I didn’t know where it would lead, for I hadn’t planned to continue teaching when I moved back to Italy.

Curiosa: You didn’t plan to teach?

Diego: No, I planned just to give training but not teaching, I didn’t want another big commitment. Because it’s a lot of work to be responsible for a group. It can be huge or it can be nothing if you don’t take it seriously.

Anyway, we started out few. Now the group has 20 persons; they are all very happy people, some of them are committed, some of them are less committed, but it’s fun nonetheless.

Curiosa: Nadav said that 2 of his students went to you?

Diego: Yes.

Curiosa: He said he would recommend you to his students if they can't train with him.

Diego: Yeah. It happens that some students might have difficulties with a group or with a teacher…

Curiosa: Or with a place or with a metro…

Diego: Whatever may be the case. It’s better that they continue training with someone else than stopping.

I mean in Shanghai, I had up to ten thousand students in ten years who have trained with me at least once. Everybody left Shanghai after a while (I am speaking about the expats) and for me the important thing is that they would continue to practice.

Curiosa: Is this a common experience with expats?

Diego: Yeah, it was tough. They were getting good and then they were leaving, they were getting good and then they were leaving. It’s frustrating but now…

Elisa (Diego’s wife): There were people who were coming and leaving but there was also a core group that was always there.

Curiosa: How did you both meet?

Diego: In Napoli, in the same university. We were not in the same class, but she was studying Chinese. After we met, in the same day, I said to her, “You know, tomorrow there will be a capoeira roda in the street.” So, I invited her to see a capoeira roda, but she didn’t go.

Elisa: I didn’t go.

Diego: And she didn’t go.

Elisa: I knew about capoeira, but I didn’t think of practicing.

Curiosa: How did the move to Shanghai come about?

Diego: I moved first, and then she moved a few months later and started capoeira a year later.

Elisa: At first, I was just going to the university classes to study Chinese but then I thought that I needed to do some sport. He was always going to the park, and I wanted to see what made it so interesting.

Curiosa: And now you are an instrutora?

Elisa: Yes.

Curiosa: Well done. Now back to Shanghai. Did you need to comply with an legal process to rent a space and teach?

Diego: No, in Shanghai you need nothing; you just teach. I paid the rent in cash at the time and I gave classes. Yeah, there was nothing to be done: no status, no registration, no association. Nothing, zero.

Curiosa: Did you have to advertise to attract more students?

Diego: In the beginning, there were just friends of friends that were coming. So, it was more of word-of-mouth advertising. Then of course, we had these magazines for expats where we posted our news. Then through this network… In the beginning it was an amazing network. Do you know that in 2016, during the World Cup, we were performing capoeira in the middle of the night when Brazil was playing? And we were doing capoeira in that place with the Brazilian community. We just had a lot of contacts!

Elisa: We also gave performances in local schools

Curiosa: Did you have children among your students?

Diego: Not in the beginning, but after, we did have classes for kids. My wife started to teach them; I taught a few classes only. But since the only day available was Saturday, she was teaching kids on Saturdays before our regular class. It still happens in Shanghai in the same format. But it was never for me to teach kids.

Curiosa: Capoeira Brasil is now in Shanghai. When they first arrived, did you communicate, did you get along?

Diego: There was Instructor Tanque, a really cool guy. I don’t remember which year they arrived in Shanghai, but I do know that I was a little worried or maybe even scared. But eventually they turned out to be very nice people, I never had any issues with them. I was going to their events and they were coming to ours. We always had a good relationship. And given that their style was different from ours, if was fun training with them.

Curiosa: Have you ever had some sort of crises in capoeira when you had doubts or wanted to stop?

Diego: Sometimes… Sometimes yes, it was overwhelming. Especially when I was training with Ido Portal, I was training four times a day!

In the morning I was working on my mobility and shoulders, then I had work, at lunchtime I was doing my strength routine, then I returned to work, then back at home I would work on my handstand. Then I would go to do give a class, and I was also teaching personal training, (though not for long). So yes, sometimes I was very tired when I considered everything. But most of the time, my thought was just to quit my job and do capoeira. So, the crisis was more on the other side.

Eventually, I decided to keep my job for my stability and to keep enjoying capoeira and not depend on it for my financial needs. Because I realized that it is a risky business anyway, and I don’t want to depend on my body.

Curiosa: You have already said a lot about your students, but your Chinese students, who are they? Why do they come? What are they looking for? Are they young or old?

Diego: They are mainly around 20 to 30 years-old. As to why they come, I think there are a lot of reasons. In practicing capoeira, there is a lot of freedom, improvisation, creativity and Chinese people are good at memorization. They do anything, but creativity. Just to learn to read and to write, they have to memorize a lot of characters, this is how their educational system works. So, they are very good at classes: in how to follow the sequence and how to kick. Although they are not very outgoing, as they don’t do much when they are kids. The problem is when they need to play capoeira, then, it becomes worse than trying to explain to a child what to do. Without rules they really feel lost. So, many believe capoeira can be of great benefit to them, as it might be good for them to have the freedom it offers, to improvise, to create, where they don’t need to doggedly follow rules. It is in the area of expression and creativity that they need most to improve. But then once they get it… I had a strong group of four Chinese students who were really getting it, then all of them stopped, now there is only one, he is also teaching in Shanghai. So what I’m saying is, once they get it, they can be as good as anyone.

Curiosa: And how about the Portuguese language, the songs, the music? Do they understand those easily?

Diego: Not easily; but the ones who want to learn the music, they learn, they memorize. Maybe the pronunciation is not perfect, but they learn the songs.

Curiosa: How are they with instruments? Are they musical people?

Diego: Some of them, yes. When I came to Italy I thought, “Oh, it will be easy now,” but it wasn’t. So, it really depends on the people. They are not worse or better that the others.

Curiosa: What is capoeira for you? What place/priority does it have in your life?

Diego: Capoeira is a part of my life. It has gradually become more and more important. With time I realized how beneficial it is to my mind, more than my body. My job decisions are taken based on the possibility of continuing training/teaching capoeira. It is definitely one of the top priorities of my life.

Curiosa: How do you see the future of the group in Shanghai and Milan? Any plans or projects?

Diego: The group in Shanghai/China will grow. It’s already growing and with the involvement of locals in teaching and promoting the group it will grow even faster. I was worried when I left, but now I see that Nico, Alex and all the others are doing a good job keeping good fundamentals. It will get bigger and stronger, hopefully not too fast, in order to be able to steer things in the right direction. With regards to Milan, I just want to continue enjoying training and teaching capoeira with my group. I am leveraging on my ten years’ experience in China in order to optimize my teaching, thereby allowing the students to improve at a faster pace. I really try to make the best out of the 90 minutes classes that we have. I want to have more advanced students in order to be helped in teaching classes and guiding other students. A strong core group of advanced students is the key to having a stable group. It will take time, but I’m not in a hurry.

Curiosa: How does it feel not to have a teacher next to you all the time? Who or what gives you inspiration or ideas about your own training and capoeira?

Diego: I have been teaching alone in China with less than three years of capoeira experience (where I only learned just the basics). Nowadays I have a lot of materials, I get ideas for my classes everywhere, from my own students (mistakes or games), from workshops attended elsewhere, from guests, from mestres’ sequences, from videos posted by other capoeiristas etc. What mainly guides my classes is the observation of my students, trying to understand what they need to practice in order to improve their game, what their weak points are, etc. Often their weaknesses coincide with my weaknesses.

Curiosa: What is the most memorable or funniest moment of your capoeira life?

Diego: I enjoy every moment of my capoeira life. I had so many beautiful and funny moments and funny students. It is impossible to recall a specific episode.

Curiosa: Who has had the greatest impact on your capoeira?

Diego: There are too many. I will just mention three: Mestre Marcelo, directly or indirectly through his students; CM Cipo, who was the first guest we had in 2008 and who gave three months of super hard classes: it definitely shaped my capoeira and allowed me to understand what training really means; Ido Portal: his knowledge and his way of thinking has changed my approach to movement and to life in general; I learned so much and my body has been transformed. Nowadays I’m still using his method for my own training and when teaching.

Hong Kong

I set off to Hong Kong in a happy mood — there are two CDO groups in the city!

My trip to Hong Kong from Shenzhen took only 12 minutes by train. Border control — another half an hour. I spent that much time just to get from home to work on a regular day, and then I travelled to another country in just 12 minutes!

I needed to extend my visa to China, and I left for Hong Kong for just a few hours — to wander around the city and, of course, go to a capoeira class!

And I went to monitor Kazu. Kazu was born in Japan and studied in Brazil, where he began to practice capoeira and started working with Grande Mestre Cícero, then he moved back to Japan, opened a group there, then moved to Hong Kong and opened another group here. Fuh! Didn’t seem to miss anything. When I met to Kazu, he had been teaching for only a couple of months. At his class at the time of my visit, there was one girl from Portugal with some past capoeira experience, and 3 students from Japan, they were complete newbies.

After the class, we went to drink coffee and chat. Kazu’s girlfriend also came along. She happened to be a student of the Instrutora Zoinho, who is a student of Mestre Parente and has lived in Hong Kong for several years. It was she that I had planned to talk to, but I’ll speak more to that later. She wasn’t in town that week.

Hong Kong is modern, traditional and dangerous…

Hong Kong is a city on a peninsula, which used to be a part of China, but then the UK rented it for a hundred years. One hundred years passed, and in 1997 Hong Kong returned to China.

Hong Kong won me over already at the train station — the contrast with China played its role. All apps and bank cards functioned here, there was free Wi-Fi everywhere, and everyone spoke English. Traffic in the city, like in Great Britain, is left sided. All taxis are painted red and white, fairly old Toyota models. And this all stands against the background of breathtaking skyscrapers, multi-lane and multi-level traffic. It’s a city of the future for sure. And this is so despite the fact that Hong Kong combines, it seems to me, the best that has been preserved from pre-communist China and that which was absorbed during the hundred years from the British mindset.

Traditions are seen in Buddhist temples, Chinese characters and language, which, unlike the rest of China, were not simplified in Hong Kong. At the same time, it has this cute English feature to only use double-decker buses and only allow taxis of a certain color. Hong Kong has an unbelievable number of banks and corporations and the most expensive brands in the world, which causes a feeling of inferiority in an ordinary Russian person, because, I can only go to such stores for an excursion. This I did at the Gucci store. There I was met and followed by a personal consultant, who, like all consultants, was dressed in a black trouser suit. She gave me a welcome speech in perfect English and silently, but with a smile, followed me with a tired look, knowing that I would not buy anything.

Hong Kong is a grandiose city. There you have to lift your head all the way up to see the tops of skyscrapers — I noticed I was holding my breath as I looked up. And the multi-level overpasses, which in new districts are intercrossed with shopping malls and the metro, makes your head spin and does not make tourists’ life easy. Somehow, this small peninsula also has quite a lot of greenery, mountains, beautiful views and wildlife that coexists with a crowded metropolis.

How a trip to a temple almost ended in tragedy.

During my second visit to Hong Kong, I decided to visit an amazing place — the Temple of 10,000 Buddhas. And everything seemed to be fine there: it is beautiful, has many steps, many golden Buddhas in different poses on the way to the temple, horoscope and Yin and Yang signs, jade amulets and souvenir coins for wealth. But there is one BUT — I went there on October 1st. Not that I had a choice, but it was the worst day to leave home in Hong Kong at all.

China celebrates its national day on October 1st, moreover, on October 1st, 2019, the Chinese Communist Party celebrated its 70th anniversary. Why is that bad?

Well, Hong Kong wasn’t at peace already and chaos reigned there due to mass protests. We will leave politics aside, but closed metro stations, closed streets, crowds of people in black T-shirts, uprooted and burnt ATMs created a rather overwhelming atmosphere.

I knew that the metro station next to the temple would be closed that day, so I took a bus. And everything was fine, well, except that the army of policemen on the way frightened me a little.

I was in the temple and had just found comfortable steps to take a couple of pictures upside down, when suddenly the workers began to move actively and close all the doors, saying, “Close door, close door.” It was still two hours before closing, and I didn’t understand why they were closing the doors. I assumed that they wanted to close earlier, and hastened to leave.

I got to the bus stop and started looking for my bus. I couldn’t see it anywhere, and from the information on the signs it was not clear where it was supposed to stop. Remember when I said that in Hong Kong, multi-level overpasses are intercrossed with subways and shopping malls? This was the case: there were overpasses, a closed metro station and the entrance to a multi-storied shopping center around. The bus stops were both a level above and a level below — it was not clear to me where to go.

I went into an empty shopping center, where the lights were dim, the doors to the shops were closed and taped with yellow tape, people were somehow chaotically wandering around, and the same alarming announcement was on repeat. It looked rather like a post-apocalypse…

Fortunately, I managed to connect to Wi-Fi and build a route home. But the stop was still at an unknown level, and I asked people around who informed me in an alarming voice that the buses were no longer operating due to the protests nearby. To my naive question, “How can I get out of here?” they just shrugged.

My brain began to draw scary pictures, but I hastened to get out of the web of overpasses and closed doors. I wanted to walk a couple of stops ahead, hoping that the bus stopped there. The only way out was through the mall. I followed well-dressed guys who were also clearly looking for an exit. It was impossible to see what was happening outside, as there were closed shops along the entire perimeter. Eventually, we got to the escalators that led down to the exit…

Step by step I approached the light… no, instead there were dozens, maybe hundreds of people in black T-shirts and respirators blocking the light. Firemen walked somewhere between them. There were skyscrapers and flyovers all around.

The only street went straight, my bus went along it, I had to go along it too, but it was blocked from my side by the protesters!

I still hoped that I could just walk past them further down the street, but that was not the case. Looking closely, I saw that part of the street was completely empty, and that a very large army of policemen was standing far ahead on the other side. Imagine this: I am in a bright yellow suit between protesters and an army of policemen going to look for my bus. Absurd, of course. I didn’t go anywhere, but for a couple of seconds, together with those guys, I looked around to understand where to run…

Nothing seemed to be happening, but that was clearly the calm before the storm. This was the case when intuition and subconscious worked more clearly and faster than usual. I analyzed dozens of scenarios in a minute. There was tension in the air. People around were talking, some were sitting and watching those who were in the forefront.

I remember the mixture of insecurity, calmness and fear in the eyes of the protesters. They were all very young, many did not want to be there — this was evident from the detachment in their eyes and the obvious body language: they sat sideways or even almost with their backs to the main activists, as if they were preparing to escape from there.

I was torn apart by curiosity and my self-preservation instinct. I wanted to stay, film all this and just watch — the picture was very impressive. But of course, the consequences of such curiosity could be sad. I decided to leave. I went back, not inside, but around the mall to find a way around it. There were three levels of flyovers and there were still a lot of people in black, there was no way out.

Some kind of suspicious movement began behind me, the rumble of voices was alarming, I walked faster. Ahead, I noticed those same guys, they were moving confidently towards the overpasses. Shouts were heard from behind, I turned around, and someone, looking at me, shouted in English, “Run!” And I ran.

Right near the overpass, I saw a road that went behind the building to the right and was supposed to be our way out of the danger zone. We climbed over a barricade of bags, tires, bicycles, and furniture and turned into a parallel street. Only one row of buildings separated us from the crowd. But there was another problem: there was a river ahead and it was necessary to cross the bridge. That was where my cherished bus stop was supposed to be.

And now, coming close to the crossroads, I saw a closed gate of a small square. It linked us to the bridge and to that very street with the protesters and the police. Slogans, claps and shouts started to sound. I looked at the closed gate and thought, “How strange, how did the water get into my nose? Maybe I had a flu? It was stinging inside.” A girl came out from behind the buildings that separated us from the crowd, and gave me a wet tissue. She told me: “Put it to the nose, they are using the gas.”

“Holy shit!” I thought, and with a brisk step I walked in the opposite direction, just to get away from all this. It got really scary.

There were almost no people around. Then I saw a bus stop, a bunch of people trying to leave, cars being turned around by the police. I kept walking. Judging by the map, there was another metro station nearby. I asked the locals if it was open. Yes! It was open. In total, I walked for about an hour.

In the metro, everyone was warned that 3 or 4 stations along the way would be closed. When we passed the very station from which I ran away, the train was passing above, and the very crowd was perfectly visible. It was like watching the news, but only from the window. Not bad.

I stayed alive and well, got home and cooked buckwheat for my hosts.

The next day, Zoinho finally returned to Hong Kong and I went to meet her!

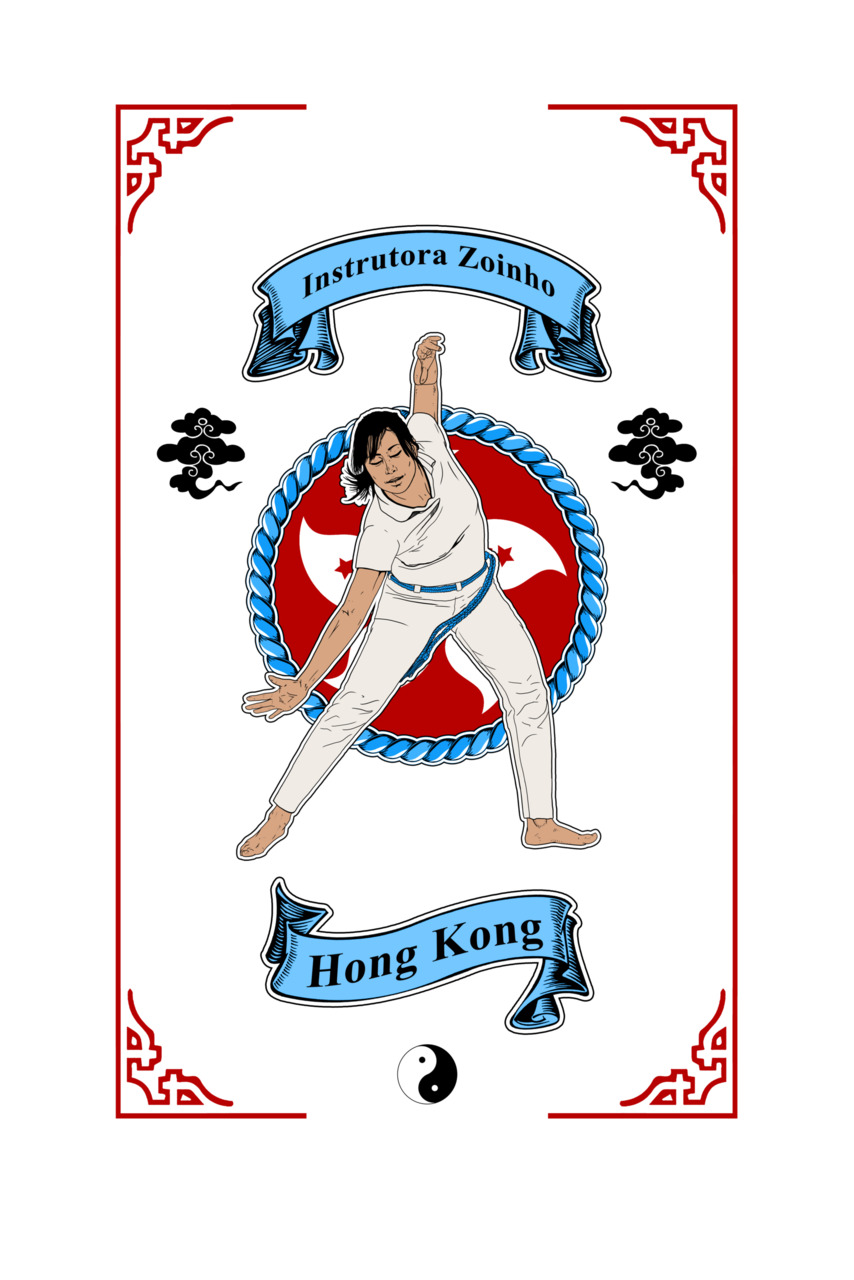

Instrutora Zoinho — Hong Kong

***

A Filipina with an American accent who grew up in Asia, spent her youth in the UK, and who fell in love with and absorbed Brazilian culture so much that she became a source of it for her students in Hong Kong, the uncatchable Zoinho.

When I came to Hong Kong for the first time, she was celebrating her birthday in the Philippines. When I came for the second time, she was somewhere in the United States for a capoeira seminar with almost the entire capo-crowd from Hong Kong. However, my patience paid off and I met her. This was my last day in Hong Kong. She landed at 6 in the morning and went to work, and then gave a capoeira class in the evening. This’s impressive!