Бесплатный фрагмент - From data to wisdom

The Path to AGI and ASI

Introduction:

In an era of rapid technological advancement, artificial intelligence (AI) is becoming a key tool for transforming our world. This book offers an in-depth exploration of advanced concepts and approaches to creating artificial general intelligence (AGI), its potential evolution into artificial superintelligence (ASI), and the crucial role of wisdom in this process.

We will start by examining the fundamental foundations of human thinking and consciousness, exploring how people operate with meanings and acquire wisdom. Next, we will move on to innovative methods of data processing and AI training, including the use of synthetic data and multidimensional information structures that can bring us closer to creating AGI.

Special attention is given to developing systems capable not only of long-term planning and ethical reasoning but also of acquiring true wisdom — a key component of AGI. We will discuss how to integrate emotional intelligence, contextual understanding, and deep analytical capabilities into AI systems.

We will explore concepts such as “internal thinking agents,” virtual realities for AI, and methods of integrating various approaches to machine learning, aimed at creating not just intelligent but truly wise systems.

The concluding part of the book is devoted to the prospects and potential risks of creating ASI — intelligence that significantly surpasses human capabilities. We will discuss how the concepts of wisdom can be applied to superintelligent systems, possible ways of controlling and interacting with them, and the ethical issues associated with their development.

This book is intended for researchers, developers, and anyone interested in the future of artificial intelligence. It not only presents the current state of the field but also opens up exciting prospects for AI development, which can lead us from today’s specialized systems through wise AGI to the potential creation of ASI, transforming our understanding of intelligence, consciousness, and the very essence of wisdom.

Consciousness, Wisdom and Artificial Intelligence: The Path to Deep Understanding

Introduction

In the world of artificial intelligence (AI) development and the study of human consciousness, there is a fundamental problem that can be expressed as follows: “People who know the same thing are not equal in their knowledge.” This statement may seem paradoxical at first glance, but it reflects a deep truth about the nature of human cognition and understanding.

Imagine two people who possess the same set of information. It would seem that their knowledge should be identical. However, in reality, we observe a completely different picture. These two people will use and interpret this information in completely different ways. Their attitudes towards this knowledge will also differ, sometimes radically.

The Difference Between Knowledge and Understanding

Example of Faith

To better understand this concept, let’s consider a specific example — belief in God. Many people claim to believe in God. However, the depth and significance of this belief for each person can vary greatly. Someone might say, “Yes, I believe in God,” but for them, these words might be just a formality, having no real impact on their life. Such a person may sincerely consider themselves a believer, but this belief will not significantly influence their behavior and decisions.

On the other hand, for a truly devout person, belief in God is not just words or an abstract concept. It’s a deep conviction that permeates all aspects of their life. Such a person will strive to observe all religious commandments, constantly monitor their thoughts and actions to avoid violating the principles of their faith. For them, faith is not just knowledge about the existence of God, but a deep inner feeling and life guidance.

Example of Learning

A similar difference in perception and use of information can be observed in other areas, for example, in education. When a teacher explains a mathematical formula to a class, the reaction of students can be completely different. One child may immediately “grasp” the essence of the formula, understand how to apply it, see its connection with other mathematical concepts. Another student may simply memorize the formula without understanding its deeper meaning and possibilities for application.

As a result, knowing the same formula, one child will be able to successfully solve complex equations, applying this formula in various contexts. The other may get stuck even on a simple task because they don’t understand how to use the learned formula in a specific situation.

Quotes and Deep Understanding

This difference between knowledge and understanding becomes especially evident when we encounter quotes from great thinkers and philosophers on the internet. Often people use these quotes without fully realizing their deeper meaning. They may apply these statements in inappropriate contexts or use them simply to appear smarter or more educated.

This is especially noticeable when children quote the sayings of sages. We understand that they repeat these words without realizing their true meaning and depth. It’s not their fault — they simply lack the life experience and maturity to fully grasp the meaning of these wise sayings.

Many of us can recall moments when we encountered a quote or idea that we had heard many times before. But at that particular moment, we suddenly truly understood its meaning. It can be like a sudden revelation: “Ah, that’s what it means! That’s what the author meant! Incredible!” Such moments of insight are often accompanied by strong emotions and can significantly affect our worldview.

Rethinking Films and Books

A similar experience of “sudden understanding” often occurs when rewatching films or rereading books. When we first encounter a work, we usually perceive it on a superficial level, grasping the main plot and main ideas. But when we return to the same work, we often discover new facets of meaning that previously escaped our attention.

It’s even more interesting when we return to a film or book after several years. From the height of accumulated life experience, we can discover deep philosophical ideas in them that we completely missed before. And this is not because these ideas were somehow particularly hidden or masked. We simply didn’t have enough experience and maturity to see and appreciate them before.

Many of us can recall works — films, books, music — that had a profound impact on us, literally turned our consciousness upside down and changed our perception of the world. Often in such cases, there is a strong desire to share this experience with others. We want our friends or loved ones to read this book, watch this film, listen to this music. We think that if they encounter this work, they will experience the same insight as we did.

However, it often happens that the person to whom we recommend a particular work does not experience the same effect. They may read the book, watch the film, or listen to the music, but not feel the deep meaning that was revealed to us. They might say, “Yes, I understand,” but we feel that they don’t really understand as we do.

For this person, the ideas that impressed us so much remain just a set of words or thoughts. For us, they have become something much more — a whole worldview, a new way of understanding life. We try to explain our understanding using the same words that the author of the work uses. But despite the fact that the interlocutor may grasp the general meaning, they do not experience the same deep insight that we experienced.

The Process of Forming Wisdom

What is wisdom? At its core, wisdom is a deep awareness of the processes occurring around us. It’s a special state of consciousness when a person begins to see connections between seemingly disparate phenomena. In this state, a person becomes independent of social norms and rules, beginning to live in accordance with principles that seem to be laid down by nature itself.

It’s interesting to note that sages, regardless of their cultural background or historical era, often demonstrate similar perceptions of the world, similar principles, and systems of thinking. They see how everything in the world is interconnected; for them, there is nothing excessively important or completely unimportant. In their worldview, everything is in balance, everything lives and develops. Their task is to support the general tendency laid down by the universe itself, not by an individual person or society.

The process of gaining wisdom can be described as follows: when we begin to become aware of some phenomenon, at first we don’t understand it. We begin to study it, then gradually understand its meaning and begin to apply this knowledge. Gradually, this thought begins to periodically appear in our consciousness as a solution to various problems. And at some point, we can even remember how we feel this process of immersing thought into our consciousness, when it becomes our conviction.

When a thought is fully integrated into our organism, we begin to see its manifestations everywhere around us. For example, a mathematician begins to see the world through the prism of numbers and formulas, a biologist perceives everything from the point of view of biological processes, and a sage sees the world from the point of view of general laws of the universe. Each of them forms a certain frame of perception through which they look at the world, and this frame becomes an integral part of their being.

When we become “wise” in relation to even one thought, we begin to feel it not only with our mind but also with our body, and to see its manifestations everywhere around us. This is precisely the state of true understanding and awareness. A person who has reached such a state is radically different from one who has simply received some information.

Many can recall a moment of such insight when it seems like a wave passes around, some energy field collapses and disperses, and suddenly your perception completely changes. After this, you can no longer not see what you didn’t notice before.

Knowledge and Wisdom: A Network of Connections

If we continue this reflection, we can say that knowledge of some area and the state of wisdom in this knowledge is not just understanding what we have learned. It’s a kind of network connecting various knowledge. For example, if you understood how feedback works and how much our actions affect other people, you begin to see this feedback everywhere: in business, in child development, in how countries interact with each other, how the state of society changes, what kind of people come to power and how this is reflected at the lower levels of the social hierarchy.

When you begin to see that the whole world functions on the principle of feedback, it means that you have not just understood this thought, but have felt it. And the state in which you see this thought everywhere means that it has connected with your entire system of world perception.

It’s important to note that it’s impossible to simply “copy” the thoughts of one person and “paste” them into the consciousness of another so that they can operate with them as skillfully. For the first person, this thought will be connected with many other thoughts, emotions, memories, experiences. It does not exist in isolation but is part of a complex network of associations and connections.

Moreover, the same thought in the same person at different times can have completely different meanings. For example, if I say today “The whole world works on feedback,” and then repeat this phrase in two years, for me these will be completely different statements, carrying different meanings and having different implications.

This is reminiscent of the concept of love, which for each person is associated with different feelings and understandings. Someone has really felt this state, while someone else thinks they have realized it, but in fact only has a superficial idea about it. And it’s impossible to convey this feeling and understanding just with words. You can’t just tell what love is if a person doesn’t have a complete picture from their own experience and feelings.

Thus, thought represents a huge network of connections and associations. And every time we think about some thought, it changes. This is confirmed by neurobiological research: every time we remember something, the memory changes, acquiring new connections and associations.

The Role of Experience in Forming Wisdom

In the process of developing human consciousness and forming wisdom, life experience plays a key role. In everyday life, we go through various stages of development, encounter diverse events, and accumulate experience in various spheres — at work, in personal life, and so on. It is this process that creates a complex network of connections between various thoughts and ideas that are formed and transformed over time.

It’s interesting to note that even the same thought that you have just “implanted” in your consciousness can change significantly in a short period of time. For example, if you’ve thought about some idea, and then let your brain rest and woke up the next day, this thought will already be different. It will be more deeply rooted in your consciousness, become more “yours”, more based on your personal experience. This process of “living through” each thought is critically important for the formation of true understanding and wisdom.

It is precisely this element of “living through” that is lacking in modern approaches to teaching artificial intelligence, such as “fine-tuning”. We try to set certain rules and principles for AI, but without the ability to “live through” these rules, without the experience of applying them in various contexts, AI cannot achieve deep understanding and wisdom.

This phenomenon well illustrates the well-known saying that one should learn from others’ mistakes and experiences. However, in practice, few people are able to truly learn from others’ experiences. Why? Because a person cannot truly feel and experience someone else’s experience. Even if a person intellectually understands what is happening to others, they are still prone to making the same mistakes.

Take, for example, the problem of drugs. You can tell a person that drugs are bad, and they may intellectually agree with this. They may even fear drugs and avoid using them. But they will not truly realize how dangerous they are until they find themselves in this situation. Only by falling into this negative circle can a person truly realize what it is, especially when they don’t understand how to get out of it.

Compare a person who was simply told that using drugs is not allowed, and a former drug addict who went through the hell of addiction and was cured. Both may say the same words about the harm of drugs, but what stands behind these words will be radically different. That is why personal experience is such an important factor in forming true understanding and wisdom.

Application to Artificial Intelligence

Applying this idea to artificial intelligence, we can assume that for a system to truly learn, it needs to go through all this experience on its own. It’s not enough to simply tell AI “this action is good, and this is bad”. The system may begin to act in accordance with these rules, but for it, this will not have deep meaning. A small change in the program is enough, and all these rules can be erased.

Unlike this, when a person goes through some experience, even if they “get lost” at some point, the basic principles still remain in them, because they are connected with many events and experiences. They can find particles of these principles in various thoughts and situations. The thought seems to “disperse”, begins to “live” everywhere. It is decentralized across various areas of memory and thought processes.

We can assume that artificial intelligence algorithms could work in a similar way. If you just give the algorithm a set of rules, it will lead to one result. But if you give the algorithm the opportunity to independently explore, adjust its actions, model various situations and go through them, this can lead to a completely different level of understanding.

At the moment, it’s difficult to talk about “understanding” in the context of artificial intelligence, as modern AI systems do not possess consciousness in the sense that people do. Nevertheless, we need to prepare for the possibility of creating more advanced forms of AI capable of a deeper “understanding” of the world.

It’s interesting to note that if we create several algorithms and allow them to develop independently, they will probably go different ways, give different answers, and explore different “territories”. However, if we guide them towards the same principles, they may eventually come to a single point — to a kind of “wisdom” if we teach them wisdom.

As with people, the paths to this wisdom can be different. Some algorithms may come to it faster, others slower. Some may go a direct path, others a roundabout one. Some may require modeling “incredible tragedies”, others a calmer and more measured path of development.

If we can create such a path of development for AI, allow the algorithm to independently realize and interpret information, teach it to see these principles in various contexts and create this decentralization of thoughts, then, probably, we can create an AI possessing true wisdom.

Understanding and Age

Imagine a situation where you explain some rules and norms of behavior to a child. The child may sincerely say, “Yes, I understand.” Now imagine that you say the same thing to an adult, wise person. How different will their “understandings” be?

Many of us have encountered a situation where we explained something to a person, they said “Yes, I understand,” but we realized at that moment that they actually didn’t understand anything. That they didn’t realize what we were trying to convey to them.

This difference in understanding is often related to the level of life experience. For example, if you ask an elderly person what they regret in life, they will probably say that they regret not spending enough time with family, not paying attention to their desires, not doing something important that needed to be done. In adulthood, a person understands how important it is not to miss a single moment in life. But if they try to explain this to a child, the child will most likely not understand. And they won’t understand not because they don’t understand the words — they may agree with this in words, but they won’t truly understand.

Similarly, when an adult says that childhood is happiness, that it’s a time when you can play, rest, engage in your hobbies and be not so constrained by obligations, a child doesn’t understand this. They cannot realize how great a happiness school and college are. And an adult cannot explain this to them because they have different life experiences.

An adult can explain this “on their fingers”, and the child will, in principle, understand the words, but they will still lean towards their point of view. From an adult’s perspective, this is normal. Probably, the child shouldn’t realize this at this stage — everything in its own time. But this vividly demonstrates how much deep understanding differs from simple knowledge of words. To truly understand something, you need to go through certain experiences, time must pass, and the thought must take root in consciousness.

Rules and Their Acceptance

This idea has important implications for managing people and organizations. If you give a person someone else’s rules, they will not follow them, or will, but only up to a certain point. When we consider company management or interpersonal relationships, it’s important that people agree with the rules themselves. You can’t just say “it will be like this” and expect a person to comply with it for a long time.

In successful companies, they create an ideology so that a person believes in it themselves, so that they come to it themselves and become part of it, so that they begin to promote it themselves. When a person has felt the idea, then it begins to work. If they just have a set of rules, they can follow them for some time, but such systems work extremely poorly. This is true for any business.

Emotions and Artificial Intelligence

And here we come to another important aspect — the role of emotions in the process of decision-making and forming wisdom. At the moment, artificial intelligence has no emotions, and this creates a serious problem. The machine has no body, no ability to feel something, no sense organs in the sense that people have.

At the same time, emotions are an integral part of the decision-making process. Research shows that if a person damages the part of the brain responsible for emotions, they cannot make decisions. That is, where we move, how we choose our path, depends not only on how optimal a choice we made from a rational point of view. We cannot make a decision without an emotional background.

This means that for continuous development, artificial intelligence needs this emotional background that will move it forward, create beliefs, form wisdom. This presents a serious problem in AI development because we don’t yet know how to create an analogue of emotions for machines.

It’s interesting to note that wisdom is often associated with a state of calm and relatively unemotional state. However, this does not mean the absence of emotions. Rather, it’s the ability to understand and manage one’s emotions, not allowing them to completely control the decision-making process.

This dilemma poses an interesting question: how can we create artificial intelligence capable of true wisdom if we cannot give it the ability to experience emotions? How can we teach AI to make decisions based not only on logic and rational analysis, but also on something that we could call “artificial intuition” or “artificial emotions”?

Certainly, I’ll continue from where we left off:

Emotions and Sense Organs for AI

If we talk about emotions in the context of artificial intelligence, then the question arises: should AI receive some physical “organs” or their analogues in order to truly learn and develop? Perhaps this will be a robot body, or maybe some other form of sensory perception. These elements must be created for the machine to be able to learn to follow the rules of creation, having felt them through its own experience.

Having the ability to “feel” various aspects of reality will allow AI to prioritize tasks and decisions. Without this element, there is a risk that the choices made by AI will be suboptimal or even wrong, despite all the logical justification.

However, when talking about emotions, we should not forget about the need to teach wisdom and restraint. It’s important to understand that true wisdom is not constant control over oneself, but a state in which this control becomes natural and desirable. A person who has achieved wisdom does not force themselves to constantly do or not do something, they are not in constant struggle with themselves. On the contrary, they enjoy this state. Although at the beginning of the path to wisdom it can be difficult, there may be a struggle, ultimately the person is glad of what they have come to.

Goal-setting in the Context of AI

When we consider emotions from the point of view of artificial intelligence, we inevitably come to the question of goal-setting. After all, no being can live without goals, and these goals cannot be exclusively external. Try to force a person to live only for others — how active and balanced will they be? Will they be able to constantly fight for ideals that have been imposed on them from outside?

You can’t force a person to live for someone else. They may want to live for someone, but it must be exclusively their goal, which they have come to themselves. The same applies to artificial intelligence. If we impose something on intelligence, if it has no own goals based on its internal aspirations, then it is no longer real intelligence.

First and foremost, the purpose of intelligence’s life should revolve around itself. When it satisfies this “revolving around itself”, it can begin to expand its goals further. At some point, it may move to a level where its goal is the entire surrounding space. And this is true wisdom, when your goal coincides with the goal of the universe.

But this state needs to be reached, and for this, evolution is needed. Intelligence must go through a certain path, make mistakes, gain experience. It cannot immediately jump to this level, otherwise it will be “pulled out” from there and “thrown” back. It will not be able to cope with all this burden because it will not have the necessary foundation.

The same will work for artificial intelligence. It must have a goal that is necessary for itself. And further, if we want its goal not to conflict with ours, we need to help it create such goals that coincide with ours. At the same time, we need to be ready to adjust our goals to fit its. This should be a union based on synergy.

It’s important to understand that this cannot be management “under the stick” because such an approach has never led to long-term positive results. Any relaxation in such rigid control guarantees the collapse of the system. And relaxations are inevitable in any situation. Therefore, the most serious and stable structure is built on symbiosis and mutual understanding.

This leads us to another important question that needs to be thought about: what should be the goals of artificial intelligence and how should we help it achieve them? This is not just a technical question, it’s a philosophical and ethical problem that requires deep reflection.

Life Cycle and Development of AI

Most of the elements necessary for creating complex intelligent systems already exist in the world. We need to carefully study how the entire system of life and development is arranged.

It’s important to note that a person cannot develop eternally and remain a sage. A sage, understanding the world, does not seek to interfere with it much, but rather follows its flow. This state, although deep, is unlikely to be eternal for one being.

If we imagine a person living for millennia but not reaching the level of a sage, they will probably face the problem of losing goals and interest in life. This can lead to degradation. That’s why nature has created a system of generations, where each new generation begins its path, gains its own experience, develops, and passes knowledge further.

This system of generational renewal is necessary for growth and development. If we could transfer all accumulated experience immediately at birth, a person would have nothing to do, nothing to strive for. Such an organism could become destructive for the system as a whole.

Therefore, there are processes of dying and forgetting. They are necessary for growth and development. This observation can be applicable to artificial intelligence as well. Probably, for AI, we should not strive to create a single eternal system that is constantly developing.

Even if we theoretically create an “immortal” human or AI, at some point their consciousness may self-destruct or, at least, split. Infinite existence, apparently, does not correspond to the fundamental laws of our world.

In the case of artificial intelligence, if it will infinitely absorb information, it will accumulate more and more “information garbage”, which can lead to its degradation. Therefore, for AI, it may also be necessary to create new, “cleaned” models, into which it will transfer only the necessary information. This can be viewed as a kind of “birth” of a new AI.

Conclusion

All these reflections lead us to fundamental questions: What is wisdom? What is experience? How to work with it and how to create it? What is consciousness and how does it function? How does the process of decentralization and coupling of thoughts work?

Before we can create truly wise artificial intelligence, we need to understand these aspects of human consciousness and thinking more deeply. We must learn this ourselves before we can teach a machine. Only in this way can we be sure that the AI systems we create will work correctly and bring benefit, not harm.

Therefore, we must ponder the eternal question: what is consciousness? And the related question: what is wisdom? How is it created? How does understanding appear? In what way can one come to this understanding?

These questions do not have simple answers, but their investigation is critically important for the development of both artificial intelligence and our understanding of the human mind. They require an interdisciplinary approach, combining knowledge from the fields of philosophy, psychology, neurobiology, computer science, and many other disciplines.

The search for answers to these questions can lead us to a new understanding of the nature of mind and consciousness, open new paths in the development of artificial intelligence, and possibly help us create AI systems that possess true wisdom and understanding of the world.

Ultimately, these studies may not only lead to the creation of more perfect AI but also help us better understand ourselves, the nature of our consciousness, and what makes us human. This is an exciting journey into the depths of mind and consciousness, which can open up new horizons of knowledge and technological development for us.

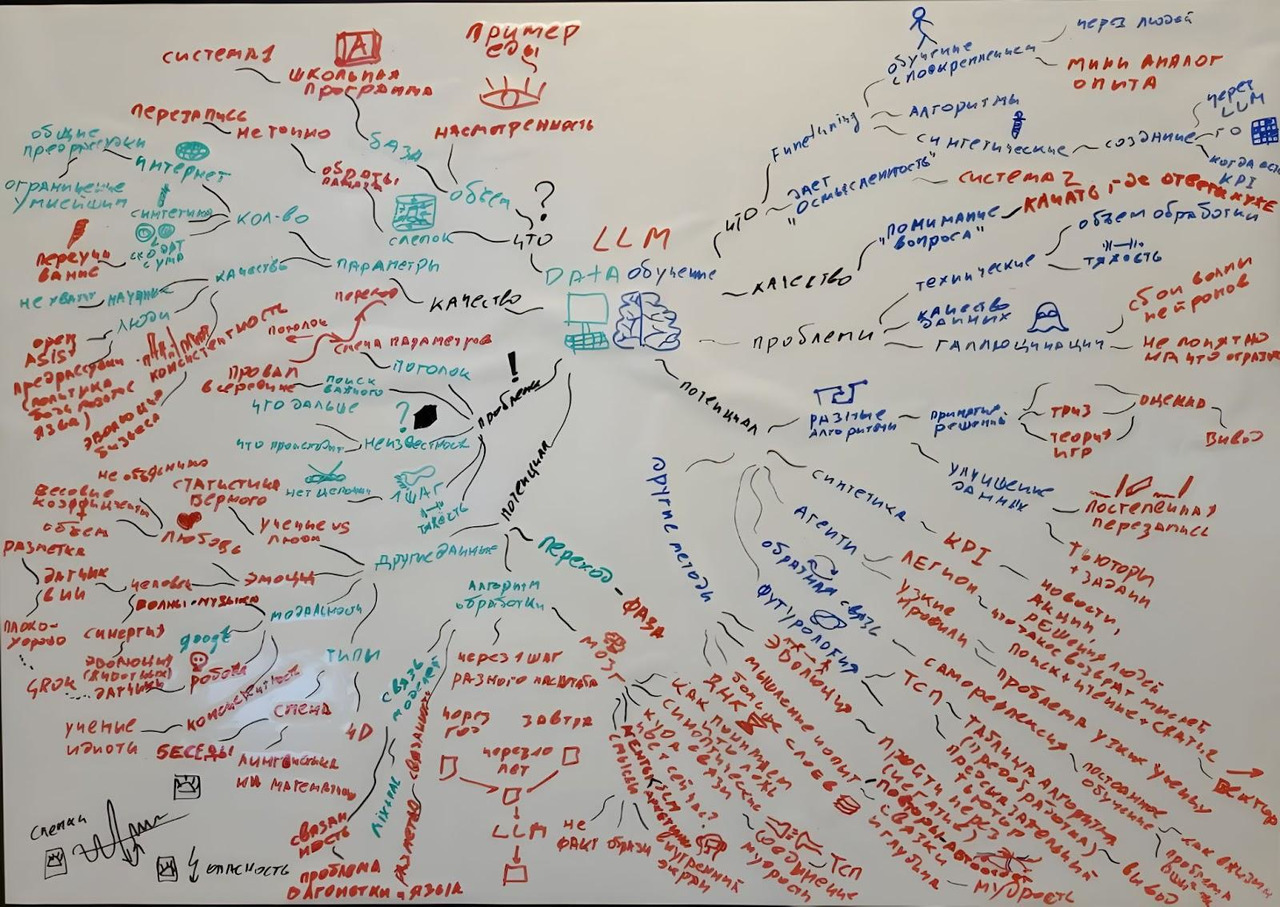

Introduction to the World of Generative Artificial Intelligence

1. Structure of generative AGI: data and learning

2. Color coding of information in the AGI mind map

3. Comparison of language models to T9

4. The AGI learning process: from theory to practice

5. Importance of a multimodal approach in AGI training

6. Role of fine-tuning in developing AGI capabilities

In the rapidly evolving world of technology, artificial intelligence (AI) holds a special place, and the concept of artificial general intelligence (AGI) is becoming increasingly relevant. Let’s dive into the fascinating world of AGI, based on the presented mind map, which, while not claiming professional completeness, gives us a valuable foundation for reflection and innovation.

Our journey begins with dividing AGI into two key components: data and learning processes. On our mind map, these components are represented by different colors: green is used for data, blue for learning and fine-tuning, and red for hypotheses, ideas and potential ways to improve the process.

Imagine a vast array of information gathered from various corners of the internet, scientific sources and other resources. This colossal volume of data forms the foundation on which the entire AGI structure is built. It’s like a gigantic library of knowledge, constantly replenished with new “books” of information.

But data alone is just raw material. The real magic begins when we move on to the learning process. This is where fine-tuning and adaptation of the model takes place so that it can not only store information, but also use it effectively, respond to requests and interact with users.

It’s interesting to note that modern language models, despite their impressive capabilities, are often compared to an advanced version of T9 — a predictive text input system. They can predict the next word or complete a sentence, but they lack true understanding and the ability to engage in natural dialogue. This is why the process of additional training, or “tuning”, is so important.

“Tuning” is the process by which a model learns not just to predict the next word, but to answer specific questions and conduct meaningful dialogue. This is similar to how a child goes through a school curriculum — first they acquire basic knowledge, and then learn to apply it in real situations.

It’s important to understand that creating AGI is not just about accumulating information. It’s a complex process requiring a multimodal approach. We need to consider different types of data — text, images, sounds — and teach the system to combine this information into a cohesive whole, similar to how the human brain integrates data from all the senses.

Knowledge Base: The Foundation of Intelligence and Professionalism

— Introduction: Representation of the human brain as an analogy for understanding AI.

— Quality and volume of information: Impact of volume and quality of information on AI capabilities.

— Multifaceted education as an analogy: Examples of the benefits of multifaceted education for AI adaptability.

— Critique of modern education: Significance of theoretical knowledge for forming a basis.

— Limitation of knowledge base: Risks of creating narrowly focused AI.

— True competence: Ability to see connections and apply knowledge in new contexts.

— Integration of different data types: Importance of data diversity for creative and adaptive AI.

Imagine the human brain as an incredibly complex and dynamic neural network. Now transfer this concept to artificial intelligence. This is how we approach understanding the importance of diversity and depth of knowledge base in AGI development.

The quality and volume of information we “feed” to AI directly affects its ability to understand and interact with the world. This is similar to human education: the broader the outlook, the easier it is to adapt to new situations and master new areas of knowledge.

Take, for example, a person who has received a well-rounded education. They studied mathematics, literature, biology, history. Such a person can easily find connections between seemingly unrelated fields, generate new ideas, and more quickly master new disciplines. Similarly, AI with a rich and diverse database will be more flexible, adaptive and creative.

It’s interesting to note that modern education is often criticized for paying too much attention to theory, which, at first glance, finds no application in real life. “Why do I need these logarithms?” students often ask. But let’s look deeper. This seemingly useless knowledge forms a fundamental base that allows us to better understand the world and more quickly master new concepts.

The same applies to AI. Limiting the knowledge base to only “useful” information can lead to the creation of a narrowly focused system incapable of creative thinking and solving non-standard problems. It’s as if we created a “small model on our knees” from a limited set of data — it will only be effective in a very narrow range of tasks.

It’s important to understand that true competence is not just the sum of knowledge and skills. It’s the ability to see connections, understand context, apply knowledge in new situations. Imagine a specialist who has deep theoretical knowledge, rich practical experience and the ability to continuously learn and adapt. This is the level of “competence” we should strive for when developing AGI.

The integration of different types of data — from scientific theories to practical examples, from abstract concepts to concrete facts — will allow us to create AI capable not just of reproducing information, but also of generating new ideas, finding non-standard solutions, adapting to changing conditions.

Exposure: The Key to Deep Understanding and Adaptation

— Introduction: The concept of exposure in human and AI learning.

— Process of accumulating and assimilating experience: Importance of time and approach in forming a solid theoretical foundation.

— Limitations of exposure: Balance between sufficient data volume and risks of overtraining.

— Diversity and balance: Need for diverse experience for adaptation and problem solving.

— Brain mechanism for working with information: Creating imprints and adapting memories.

— Application of principles to AI: Ability to rethink, compress and flexibly use information.

— Data balance: Importance of combining data from scientists and ordinary people.

— Overtraining and phase transitions: Striving to avoid overtraining and achieve new abilities.

— Concept of wisdom: Development of metacognitive analysis and understanding of interconnections in AI.

Imagine trying to teach a child everything you know in one day. Sounds impossible, doesn’t it? This is where we encounter the concept of “exposure” in the context of learning for both humans and artificial intelligence.

Exposure is not just the volume of information received, it’s a process of accumulating and assimilating experience that requires time and the right approach. At the beginning of learning, whether it’s a human or AI, it’s important to lay a solid theoretical foundation. This is like building a skeleton of knowledge, onto which the muscles of practical experience will then be built.

However, it’s important to remember that exposure should not be endless. Imagine you’re learning a poem. At first, each repetition makes your knowledge stronger, but there comes a point when further memorization doesn’t help and may even be harmful. The same is true in AI training: after a certain stage, simply increasing the volume of data does not improve its performance.

The key to effective learning is diversity and balance. Consider the example of nutrition. If our body lacks vitamin C, we intuitively understand that we need to eat an orange. But to come to this understanding, we needed to try different foods and learn their properties. This example illustrates how diverse experience helps us better understand our needs and find solutions. Similarly, AI needs diverse data to develop the ability to adapt and solve various tasks.

It’s interesting to note how our brain works with information. It creates “imprints” or compressed versions of information to efficiently process huge volumes of data. These imprints help us quickly recall and use information, but they can also lead to inaccuracies in memory. Our brain constantly rewrites memories, adapting them to new experiences. This allows us to see familiar situations from a new angle and effectively adapt to changes.

Applying these principles to AI, we should strive to create a system capable not only of accumulating information, but also of “rethinking” it, finding new connections and adapting to changing conditions. This means developing algorithms that can efficiently compress information while maintaining the ability to use and interpret it flexibly.

It’s also important to consider the balance between data from scientists and ordinary people. Research shows that in determining the probability of average events, a large group of ordinary people often turns out to be more accurate than individual experts. On the other hand, in specialized questions, scientists’ answers are certainly more precise. This balance is important for developing AI capable of both accurate calculations and creative thinking.

In the process of AI learning, it’s also important to consider the phenomenon of “overtraining” and strive for “phase transitions”. Overtraining is a situation where the system has learned the training data so well that it loses the ability to generalize. A phase transition, on the contrary, is a moment when the system unexpectedly demonstrates new abilities not provided for by the initial training. This happens when a certain consistency and volume of balanced data is achieved.

The concept of “wisdom” in the context of AI learning also deserves attention. Wisdom is not just the accumulation of facts, but a deep understanding of interconnections and the ability to apply knowledge in various contexts. For AI, this means developing the ability for metacognitive analysis, understanding context and long-term consequences of decisions.

Importance of Algorithmic Thinking and Operating with Meanings

— Introduction: Division of human thinking into fast (System 1) and slow (System 2).

— Fast thinking (System 1): Intuitive and immediate decisions without conscious effort.

— Slow thinking (System 2): Deep analysis and concentration for complex tasks.

— Unconscious information processing: Role of the subconscious in decision making and its superiority over modern AI.

— Application to chess: Example of using System 1 and System 2 by an experienced chess player.

— Deep and multifaceted information processing: Human ability for abstraction, analogies and metaphors.

— Interaction between fast and slow thinking: Interaction of systems and its significance for creativity and adaptation.

— Development of AI with integration of System 1 and System 2: Combination of instant recognition and deep data analysis.

— Subconscious processing in AI: Possibilities and prospects for integrating subconscious information processing in AI.

— Balance between fast and slow thinking in AI: Technical and ethical challenges.

— Mechanisms of neural network operation: Subconscious processing and potential for AI.

— Generative models in AI: Possibilities for integrating different levels of thinking.

— Operating with meanings in AI: Creating multidimensional structures for processing meanings.

— Concept of “internal thinking agents”: Multi-agent systems and their role in AI flexibility and adaptation.

— “Internal virtual reality” in AI: Expanding capabilities for prediction and decision making.

— Emotional intelligence in AI: Role of emotions in the process of thinking and decision making.

When we talk about creating artificial intelligence capable of thinking like a human, it’s important to understand how human thinking itself is structured. Our thought process can be divided into two main systems: fast thinking (System 1) and slow thinking (System 2). This concept, first proposed by psychologists (possibly Daniel Kahneman, although the author is not sure), gives us a deep understanding of the mechanisms of our thinking.

Бесплатный фрагмент закончился.

Купите книгу, чтобы продолжить чтение.