Бесплатный фрагмент - Eonatrika. View frow above

Preface

Eonatrika is a view from the height of the Universe and a scientific-philosophical reflection on the possible cosmic transformation of humanity: how we are structured, how our myths and scientific models change, and what future scenarios grow out of this.

This book lies at the intersection of scientific inquiry, philosophical reflection, and an authorial worldview. Facts and theories from astrophysics, biology, sociology, and related disciplines are presented in accordance with the current scientific consensus and are accompanied by references to up-to-date sources.

For the reader’s convenience, the book introduces several original conceptual models — “Eonatrika”, the “Law of Harmony”, the “Civilization Counter”, and others. Their purpose is not to propose a new physical theory, but to create a coherent image for rethinking humanity’s place in the universal drama of being. These models are philosophical constructs rather than scientific theories and serve purely as worldview- and illustration-oriented tools; they are not subject to empirical verification and are not intended for practical application.

Scientific terms are sometimes used in an extended, metaphorical sense, which is explicitly indicated in the text. This approach does not claim to alter the existing scientific consensus and functions only as an instrument of philosophical analysis. For convenience, all key terms, both scientific and authorial, are collected in a glossary at the end of the book.

How to read this book

The book is structured as a sequence of interconnected essays: from the paradox of a silent Universe and the Great Filter hypotheses to the inner contradictions of the human psyche and the idea of Eonatrika as a possible framework for humanity’s cosmic becoming. Each chapter can be read as a stand-alone text, yet together they form a single trajectory — from the description of the cosmic context to the question of inner harmony as a condition for the survival of the species.

The text does not require specialized education, but it does presuppose a willingness to read attentively and to engage in independent critical analysis. It is best approached not as a set of final answers but as an invitation to reflect and to enter into an inner dialogue about which qualities of a civilization might actually allow it to pass through the “bottleneck” of history.

Legal notice

This book is intended solely for intellectual, educational, and philosophical reflection and does not constitute guidance for action or professional advice in any field. Nothing in the text may be regarded as legal, financial, investment, medical, psychological, religious, or any other form of professional advice, nor as an inducement to perform legally significant actions.

The concepts described in the book (“Eonatrika”, the “Law of Harmony”, the “Civilization Counter”, and other authorial principles and models) are philosophical constructs rather than scientific theories; they are not subject to empirical verification and are not intended for practical application. Scientific terms used in an extended or metaphorical sense do not claim to modify the existing scientific consensus and do not constitute scientific statements, recommendations, or forecasts.

All historical analogies, interpretations of scientific theories, and psychological and sociological models are used exclusively within the framework of the author’s philosophical concept and do not claim absolute truth, completeness, or universal applicability. Nothing in this book may be regarded as legal, financial, investment, medical, psychological, religious, or any other type of professional consultation.

Reasonable efforts have been made in preparing this book to verify data and sources; however, their absolute completeness, timeliness, and freedom from error are not guaranteed. Responsibility for the interpretation and any possible use of the ideas contained herein rests entirely with the reader. By beginning to read this book, you confirm your understanding and acceptance of these conditions.

Copyright to the text and the authorial concepts belongs to Katerina Wind (pen name), 2026. When quoting or otherwise permissibly using fragments of the book, a reference to the author, the title of the book, and the year of publication must be retained.

Translation notice

This English version was produced from the original Russian text with the assistance of artificial intelligence and without additional human editing; despite reasonable care, the text may contain inaccuracies or distortions of meaning.

From the author

Eonatrika is an author’s view of humanity as an experiment in overcoming its own biological program for the sake of a cosmic future. The human being lives in a permanent inner contradiction: our thought can contemplate the Universe, yet our collective will is often held captive by narrow, pre-rational impulses.

We are the Architects of the future, capable of thinking in terms of cooperation and progress, and at the same time carriers of an ancient residual “Shadow” that splits the world into camps and seeks superiority. The collision of these levels of being on the stage of planetary civilization generates a critical tension that threatens to turn our greatest achievements against us.

Perhaps it is time to look at ourselves from the vantage point of space — and reconsider. This book is an attempt at such a view.

Invitation to dialogue

This book does not demand agreement with every thesis; it matters far more if some of the proposed perspectives help you articulate your own questions about the future of humanity and about yourself more precisely. If, in the course of reading, objections, alternative models, or a desire to extend the proposed picture arise, then Eonatrika’s task as a philosophical experiment is already partially fulfilled.

Read. Reflect. And if it resonates, find in this perspective your own point of assembly — that inner configuration from which the cosmic fate of humanity ceases to be an abstraction and becomes a personal ethical choice. After that, you can turn the page and move on to Part I, where the discussion begins with the silent Universe and the statistics of the Great Filter.

Part I. Cosmic Protocol

The silence of the Universe is the loudest signal we have ever received. The Fermi paradox confronts us with a stark choice: is our civilization a rare miracle or a solitary spark?

We feverishly scan the sky, while the Great Filter may already lie behind us… or be waiting ahead. This is not a search for our cosmic siblings; it is an interrogation of our own civilization in the face of voiceless eternity.

Chapter 1. The Civilization Counter: why does it reset?

The Universe has prepared trillions of seats, yet the hall remains empty. Where is everyone these places were made for? Or is the ticket to the “galactic club” far more expensive than we think?

In a clear night, to see the main equation of this book, it is enough to look up. Each point of light is not just a “little star” but a separate star, one of the hundreds of billions of suns in our Galaxy. Most of these stars have planets; this is no longer a conjecture but an established fact: as of January 2026, the existence of more than six thousand exoplanets has been confirmed [1].

From there, simple arithmetic takes over. According to current estimates, the observable Universe contains from two hundred billion to two trillion galaxies [2].

Each of them contains hundreds of billions of stars. A significant fraction of these stars host planets, and a certain percentage of planets lie in the “habitable zone” — the theoretical range of distances from a star where liquid water can exist on the surface as a necessary condition for the biochemistry familiar to us [3] [4].

It does not matter which estimate of the number of potentially habitable worlds we adopt. What matters is that pure statistics depict the cosmos as an environment in which life and intelligence must arise repeatedly [4].

Yet against this numerical backdrop, space remains silent. Despite the abundance of possible worlds, we see neither clear signals nor unambiguous traces of other civilizations. Around us is the light of millions of stars — and almost complete silence [5].

Why, amid such stellar abundance around us, does the cosmos remain silent? Is this silence one of the most troubling riddles the human mind has ever faced [5]?

The Fermi paradox: “Where is everybody?”

The official Search for Extraterrestrial Intelligence (SETI) has been underway for more than six decades. Formal SETI searches began in 1960, when radio telescopes were first pointed at other stars in the hope of detecting artificial signals; since then, the instruments have become more powerful, the search range has expanded, and private initiatives and new telescope arrays have joined the effort [5] [6].

The result remains unchanged: there is still no convincing, widely accepted evidence for the existence of another technological civilization [5]:

1. Radio searches have detected many signals, but all of them have been explained by natural processes or interference [6].

2. Searches for large-scale engineering structures, such as hypothetical Dyson spheres, have likewise yielded no definitive results [7].

3. Searches for other forms of technosignatures, including atmospheric anomalies and artificial pollutants, have so far produced no results [5].

Of course, we have explored only a tiny fraction of space and time. Yet even against this background, the contrast between the astronomical number of potential sites for life and the observed emptiness is so great that it has become a scientific problem in its own right. Its concise formulation was given by Enrico Fermi in a simple question: “Where is everybody?” [8].

Contemporary research on cosmic communication points to the possibility of alternative forms of contact that our current methods cannot detect, including quantum communication channels [9] [10].

Most likely, somewhere in the Universe there is life and intelligence, but at our current temporal scales and instrumental sensitivity, practical contact with them may be a matter not of thousands but of billions of years — if it is possible in any familiar form at all [5].

Regardless of whether intelligence exists elsewhere, the only real resource we can rely on is our own capacity for harmony, self-control, and re-examination of the primate code. Only this can help us pass our section of the Filter, rather than any hope of external salvation [11] [12].

Two lines of response: rarity and filtering

To systematize the hypotheses that attempt to explain the Fermi paradox, we can roughly divide them into two broad classes. Between them lies a wide range of hybrid and alternative scenarios. [11] [12] [13].

1. The rarity hypothesis. Intelligent life may be statistically almost impossible. In this view, either life itself arises extremely rarely, or the transition to complex cells is a rare event, or the development of intelligence and technology is an almost unique convergence of circumstances. From a mathematical point of view, this is possible: the Universe is large enough to allow unique phenomena even at tiny probabilities [14] [4].

2. The filtering hypothesis. Life, and even intelligence, may arise relatively often, but the transition to a stable cosmic civilization turns out to be extremely unlikely. Between these states lies one or several “bottlenecks” — filters where most trajectories break off; this idea has been called the Great Filter. It does not necessarily imply an external force; more often it is understood as a set of objective difficulties, from the emergence of life to the management of powerful technologies [11] [12] [13].

Within Eonatrika, the main interest shifts from the question “How many intelligent worlds are out there?” to “Where exactly does the Filter lie in our world?”. It may lie not only in biochemistry and technology, but also in the structure of our thinking and our social systems — in how the primate code of the tribe scales up to the level of a planetary civilization [12].

A notional civilization counter

To visualize the logic of this approach, we can use a thought experiment — a notional authorial counter of stages for any civilization. This is not an empirically observed sequence or a commonly accepted classification, but a model for reflection within Eonatrika:

1. A planet with conditions suitable for complex chemistry and a stable environment.

2. The emergence of simple life.

3. The appearance of complex (eukaryotic) cells.

4. The formation of multicellular organisms.

5. The rise of intelligent beings capable of complex culture and symbolic thinking.

6. The emergence of a technological civilization visible from space through its emissions and its impact on the planet [5] [6].

7. The transition to a stable civilization capable of not destroying itself with its own technologies and conflicts.

8. The alignment of a civilization’s trajectory with the broader structures of the Aeon — a cosmic synthesis.

9. The deliberate creation and maintenance of new worlds, from robust artificial ecosystems to the ultimate image of a Laboratory that gives birth to new “universes”.

10. Existence on timescales comparable to a substantial fraction of the Galaxy’s age.

The first six steps can be described in the language of biology and astronomy. The remaining four are a philosophical extension, an authorial Eonatrika scale that does not describe measurable stages but possible horizons of a mature civilization [12].

Humanity has apparently passed the first six steps. We live on a suitable planet where life has produced complex forms, and intelligence and culture have arisen. The last few centuries have been marked by the emergence of a technological civilization that is noticeable through its radio noise and its alteration of the atmosphere [5] [6].

But this is where the central question arises. If the path from zero to the sixth stage is passable, why do we not see those who have reached the eighth, ninth, or tenth? If the Galaxy were populated by many long-lived civilizations, we would expect to see at least some traces of them. So far, no such confident evidence exists. This is not proof of absence, but it is a serious argument that the transition to a stable cosmic stage is associated with a high risk of collapse [11] [12].

Where might the Great Filter be located?

The concept of the Great Filter is a theoretical framework. Its value lies in the way it diagnoses our position. The question of where the Filter is located determines how we envision our own future [11] [12].

1. The Filter is behind us. In this scenario, the key difficulties fall on the early stages: the emergence of life and of complex cells. Intelligence and technological civilization are rare, but already passed thresholds. The silence of the cosmos is explained by the fact that only a few have reached our level; the hardest stages may already lie behind us [11] [12].

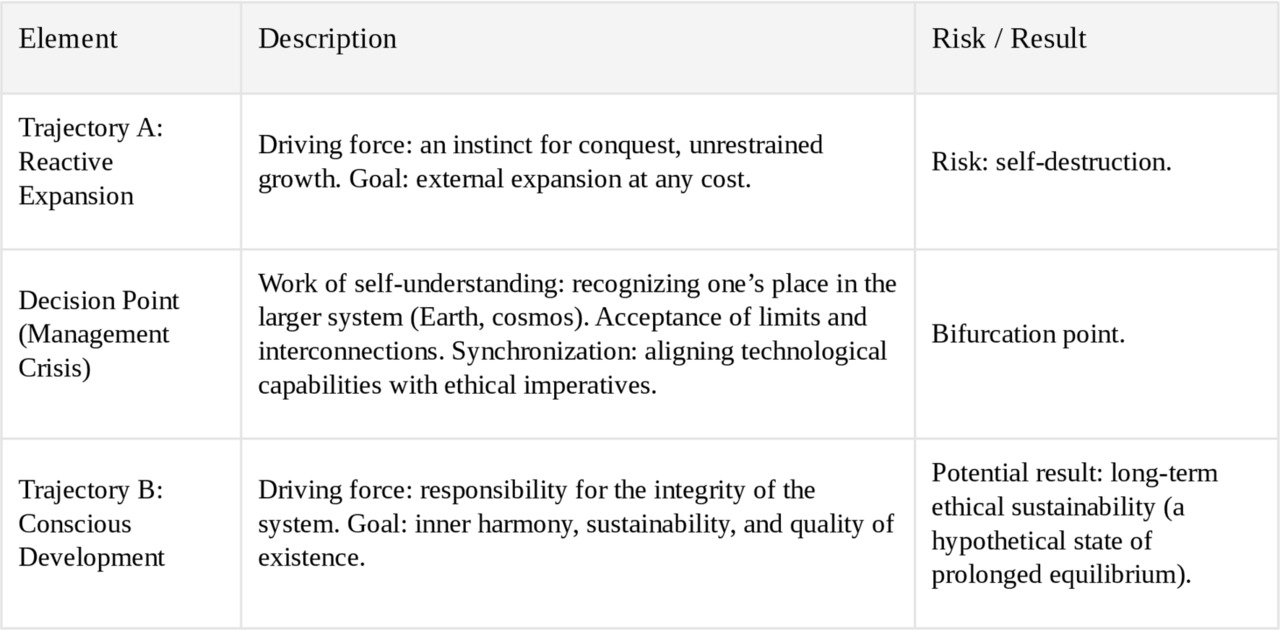

2. The Filter lies ahead of us. In this scenario, many worlds successfully pass the early stages; intelligence and technology arise frequently. Yet managing their own power turns out to be the task that almost no one can handle. This includes unstable handling of energy, conflicts involving global means of destruction, and unconsidered technological risks [11] [12] [13].

In this book, the second scenario is treated not as fate, but as a systemic governance crisis. It emerges when the complexity of a civilization exceeds the depth of its self-understanding: a critical imbalance between the power of the technologies we have created and our lagging psychological, ethical, and bioethical maturity — the capacity to recognize ourselves as part of a living system and to act in accordance with this knowledge [11] [12].

An add-on to the notional counter: Harmony as a critical transition

Humanity has long existed within a field of collective thought that arises not in isolation, but within ever more complex networks — cultural, technological, and digital. This field grows together with our tools, from the printing press to artificial intelligence, expanding access to a shared mental space but by no means guaranteeing access to Harmony.

As studies of planetary habitability show, the stability of systems depends not on one or two isolated factors, but on the subtle interaction of many parameters — orbit, stellar properties, atmospheric composition, geology, and the architecture of the planetary system as a whole. By analogy, the stability of a civilization is determined not only by its technical achievements, but also by the internal coherence of its structures — from neural networks and the psyche to institutions, culture, and the global economy [11] [4].

The problem of modern civilization lies not in a lack of knowledge, but in systemic distortions. Contemporary research in evolutionary psychology shows that our social brain is optimized for interaction with about 50–150 individuals (the Dunbar number) [15].

When a community expands to the scale of a nation or a global civilization, people still continue to think in tribal terms, which manifests itself in nationalism, intergroup hostility, and an impaired capacity for long-term planning [15].

Technological power is growing exponentially, while the mechanisms of self-control are developing only linearly. Like the Sun, which, according to modern astronomical studies, shows reduced activity compared to many similar stars, human civilization must find a way to maintain inner equilibrium amid outward development [16]. Otherwise, technological power will inevitably outpace inner maturity, creating conditions in which we encounter the Great Filter in a way that does not favor us [11] [12].

If the system can be brought into balance — by reducing its distortions, stopping the systematic removal of the competent, and embedding the principle of Harmony into culture — the probability of accelerated evolution rises sharply. In that case, a civilization need not wait for an external revelation, but can itself grow into an understanding of the Laws it now only intuitively anticipates, and, in the role of a Laboratory, create new worlds: from sustainable ecosystems to artificial “universes” as an ultimate image of a creative Aeon [12].

Our position in the Eonatrix

All this sets the context for the main theme of the book. Within the proposed model, humanity occupies a specific point in the Aeon — the sixth stage on the notional counter, the level of a technological civilization that is detectable from space.

We find ourselves in a condition where our inner programs, shaped by evolution for the challenges of small-group life, come into conflict with the demands of planetary-scale responsibility [15] [12].

Eonatrix is an attempt to discern the matrix of time in which human civilization is only one node. At present, this node lies in a zone where the decisions of a single species begin to have consequences on a planetary scale. Therefore, the question “Are we alone in the Universe?” is reformulated as a practical one: will our node become a sustainable line, or will it turn into yet another point at which the civilization counter has been reset to zero [12].

Regardless of whether other civilizations exist somewhere else, we will have to sit this exam on our own: no external force will take on the work of rewriting our primate code in the direction of Harmony [11] [15] [12].

The next chapter will show how the very structure of the Universe — its expansion and the “receding” sky — makes our window of opportunity unique.

Chapter 2. A Universe That Is Running Away from Us

Imagine a sky without stars. Not because of clouds or city lights, but because they are no longer within reach.

This is not science fiction. In 100 billion years, astronomers on Earth will see only a single galaxy in the sky — our own, merged with Andromeda — while the rest of the Universe will have slipped beyond the cosmic event horizon. The key to understanding this future already lies in the data we are collecting today.

A cosmic crisis of measurement

In 1929, Edwin Hubble revolutionized cosmology by discovering that distant galaxies are receding from us. The speed of their recession is proportional to their distance — Hubble’s law: v=H0⋅dv=H0⋅d. Today this law has been confirmed with remarkable precision, yet a new problem has emerged: a cosmological crisis.

Data from the Planck space telescope, which measured the cosmic microwave background, indicate that the Universe is expanding at 67.4 km/s per megaparsec. However, observations of Type Ia supernovae with the Hubble Space Telescope and ground-based observatories yield a value of about 73 km/s per megaparsec [17].

A 9% difference may seem small, but on the scale of the Universe it opens up an abyss in our understanding of its fate.

“This is not just a measurement error,” says Nobel laureate Adam Riess. “It may mean that we do not really understand the fundamental physics of dark energy” [18]. This measurement crisis may ultimately force a revision of the entire ΛCDM cosmological model.

Dark energy: the greatest mystery in physics

In 1998, two independent teams of astronomers made a shocking discovery: the expansion of the Universe is not slowing under the pull of gravity, but accelerating. For this discovery, the 2011 Nobel Prize in Physics was awarded to Saul Perlmutter, Brian P. Schmidt, and Adam G. Riess.

The acceleration is attributed to dark energy — a mysterious component thought to account for about 68% of the Universe’s total energy content [19].

Recent observations with the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) suggest that dark energy has behaved in a broadly stable way over the last 11 billion years, while some studies point to possible variations in its density in the early Universe [20].

The key question is: what happens if dark energy changes its properties? According to the “quintessence” model, if the density of dark energy begins to increase, it could lead to a “Big Rip” — a catastrophic tearing apart of all structures, down to atoms themselves, in roughly 22 billion years [21].

Invisible isolation: the mathematics of the cosmological horizon

Calculations show that galaxies beyond our Local Group are already receding from us at apparent speeds exceeding that of light. This does not violate the theory of relativity, because it is the space between objects that is expanding, not the galaxies moving through space faster than light.

A critical moment will come in roughly 2 trillion years, when all galaxies outside our group will have disappeared from view forever. Yet the process has already begun.

• Today, we can see on the order of 2 trillion galaxies in the observable Universe [2].

• In about 150 billion years, the number of galaxies visible from our location will shrink to only a few dozen — those belonging to our Local Group alone.

• In 1 trillion years, the cosmic microwave background will have been stretched so much by expansion that it will be impossible to detect, even with ideal instruments [22].

“For future civilizations, the Universe will appear as an empty, isolated system,” explains physicist Lawrence Krauss. “They will never learn about the Big Bang, about cosmic expansion, or about the existence of other galaxies; their cosmology will be fundamentally different” [22].

Physical limits of communication: why we are alone even in a full Universe

Even if extraterrestrial civilizations exist, physics imposes strict limits on communication:

1. Speed of light as an absolute limit. A dialogue with a civilization near Proxima Centauri (4.24 light-years away) would take at least 8.5 years for a single exchange of messages. For the Andromeda Galaxy (2.5 million light-years away), one round of communication would require about 5 million years.

2. The energy barrier. To send a signal that would be clearly detectable from a distance of 1,000 light-years would require colossal energy expenditures, far beyond the capabilities of our present-day civilization [5].

3. Expansion of space. Galaxies that lie beyond the cosmological event horizon are already receding from us so fast that any signal sent today will, in principle, never reach them: for us, they remain forever beyond the limit of causal reach [22].

According to theoretical estimates, even in a fully populated Universe the average interval between meaningful exchanges of information between civilizations would be on the order of tens of millions of years [24]. This makes any truly sustained dialog between civilizations practically impossible, since response times comparable to or exceeding the lifetimes of societies destroy the very notion of back-and-forth communication.

Our unique window in time

We live at an exceptionally fortunate moment in cosmic history:

— Past window (380,000 years after the Big Bang): The Universe was opaque — photons were constantly interacting with the primordial plasma.

— Our window (13.8 billion years after the Big Bang): The temperature is low enough for stars and planets to form, and we can observe the cosmic microwave background and distant galaxies.

— Future window (in 100+ billion years): The cosmic microwave background will fade from view, distant galaxies will slip beyond the cosmic horizon, and new stars will cease to form as the gas supply is exhausted.

“Astrophysicist Abraham Loeb notes that “the probability for a civilization to emerge precisely during this brief cosmic epoch, when conditions for life exist and the Universe can still be observed in its fullness, is extremely small” [25].

Observations from JWST indicate that the first galaxies formed earlier and were more massive or brighter than standard models had predicted. This may imply that the effective “window for life” in the Universe — the era with abundant heavy elements, active star formation and rich large-scale structure — could be narrower in time than previously assumed [26].

Eonatric conclusion: flowing time and our responsibility.

The silence of SETI takes on a new meaning in light of cosmological dynamics: it may be that we do not hear other civilizations not only because they are rare or absent, but also because the very structure of an expanding Universe, with its horizons of causal contact and immense communication delays, effectively creates a regime of cosmic isolation.

But there is also a gift hidden in this isolation: we find ourselves in that rare moment when it is still possible to see cosmic history from its beginning to the present. This grants us a unique opportunity to uncover the laws governing the evolution of complex systems, including civilizations themselves.

The expansion of the Universe not only pushes galaxies apart — it also sets temporal boundaries for the evolution of intelligence. Civilizations that arise in different cosmological epochs may end up isolated not so much in space as in time: we may well be not alone in space, yet still alone in our particular moment in time.

This shifts our task from searching for “brothers in mind” to searching for the internal laws of stability. The Universe’s silence becomes a mirror reflecting our own maturity: the time granted to us by this unique cosmological window is finite, and how we use it will determine whether we become those who unravel the riddle of existence or merely another point on the extinction curve.

Chapter 3. Sixty years of listening to silence: what does silence tell us?

Imagine shouting into space for 60 years and hearing nothing in return. This does not mean that no one is out there. It means that the silence itself is the most important signal we have received, and it tells us that something in our approach to ourselves and to the world calls for reconsideration.

Scientific efforts and accumulated data

For more than sixty years, humanity has been directing ever more sophisticated instruments toward the cosmos, hoping to catch signs of an alien mind. Modern SETI projects now extend beyond the classic search for radio signals to include optical laser bursts, atmospheric technosignatures, possible megastructures and even speculative quantum channels of communication.

Over this period, an enormous number of observations has been carried out. The Breakthrough Listen project, launched in 2015 with 100 million dollars in funding, uses radio telescopes in West Virginia and Australia to monitor up to a million nearby stars, giving it a survey scope that surpasses all previous SETI programs by orders of magnitude [27].

The 500-meter FAST telescope in China, the first radio telescope built with SETI as one of its primary scientific goals, is currently estimated to be capable of detecting signals out to a distance of about 28 light-years and to cover some 1,400 stars [28].

Yet the results so far have been discouraging. In all the years of searching, not a single universally accepted signal of extraterrestrial origin has been detected, and even the famous 1977 “Wow!” signal has never repeated and remains unresolved.

In 2022, the FAST telescope reported the possible detection of artificial signals, but subsequent analysis showed that they were nothing more than ordinary terrestrial radio interference [29].

As professor Jason Wright of Pennsylvania State University notes, if we imagine the Milky Way as an ocean, then all SETI efforts over the past 60 years are equivalent to sampling the water from something like a small swimming pool or hot tub [5].

According to modern estimates, only a vanishingly small fraction of the relevant parameter space for searching extraterrestrial civilizations has been explored so far [6].

The evolution of the search: from radio to technosignatures

Modern searches for extraterrestrial intelligence have expanded significantly. In 2018, at the request of the U.S. Congress, NASA organized a major workshop on technosignatures — potentially detectable indicators of the presence of advanced civilizations [5].

Scientists are now searching not only for radio signals, but also for:

— anomalous chemical pollutants in exoplanet atmospheres, such as chlorofluorocarbons (CFCs);

— radioactive isotopes like tritium, a byproduct of nuclear fusion;

— thermal anomalies produced by megacities or large-scale industrial activity;

— optical signals in the infrared band;

— signatures of astroengineering structures such as Dyson spheres [5].

The James Webb Space Telescope, launched in 2021, is opening up new possibilities for detecting such technosignatures. According to Jill Tarter, former director of the SETI Research Center, JWST should be able to detect industrial pollutants in the atmospheres of exoplanets, provided they are present at sufficiently high concentrations [5].

A promising new direction is quantum communication. According to a 2024 study, quantum links between stellar systems are theoretically possible, but their practical realization would require telescopes with diameters greater than 100 kilometers — a technological barrier that humanity has not yet overcome [9].

This limitation, by itself, may serve as a plausible explanation for the Fermi paradox, since the requirement of such enormous telescopes would make interstellar quantum communication effectively inaccessible to civilizations at our technological level.

Possible interpretations of the silence of the Universe

The silence of SETI admits several plausible explanations, none of which can yet be ruled out:

1. The rarity hypothesis. Technological civilizations may be an exceedingly rare phenomenon. As Stephen Webb has systematized, there are dozens of distinct proposed solutions to the Fermi paradox [30].

2. The method-mismatch hypothesis. We may simply be searching for the wrong kinds of signals. Advanced civilizations could prefer optical or even quantum communication channels over traditional radio waves, making their transmissions effectively invisible to our current search strategies [5].

3. The time-mismatch hypothesis. The technological epochs of different civilizations may be brief and fail to overlap in time. As astrophysicist David Grinspoon notes, many civilizations may be merely “proto-intelligent,” ultimately self-destructing at early technological stages instead of reaching long-term stability [5].

4. Alternative hypotheses. These range from the “zoo hypothesis” — the idea that advanced civilizations deliberately avoid contact and simply observe us — to proposals about technological transcendence into post-biological or “inner space” forms that leave few or no conventional traces in the observable Universe [13].

The Drake equation and the Great Filter in light of new data

Today, the Drake equation can now be partially filled in with precise estimates. [23].

The discovery of more than six thousand exoplanets has shown that planetary systems are the rule rather than the exception [1].

However, the key factors, especially the parameter L — the average lifetime of a technologically detectable civilization — remain in the realm of deep uncertainty.

The Great Filter concept offers a harsh but productive framework for interpreting the silence. If the universe is full of potentially habitable worlds yet we see no signs of advanced civilizations, then there must be one or more critical barriers on the path from non-living matter to a spacefaring species [13].

Within this line of reasoning, SETI’s silence may serve as indirect evidence that humanity has not yet passed the most serious filter. According to estimates by astrophysicist Sebastian von Hoerner, the average lifetime of a technological civilization may be only 6,500 years [13].

Principle of Osmosis: A Strategic Conclusion from Sixty Years of Silence

The collected evidence leads to a strategic principle that, within Eonatrica, can be called the Principle of Osmosis:

Sustained expansion of a system into a new environment becomes possible only after it has achieved internal balance and deep self-understanding. This is not a scientific law but a worldview-level principle.

For a civilization, this means that our readiness for space should be measured not only in tons of fuel but also by the quality of our social contract, the resilience of our psyche to long-term challenges, and the maturity of our understanding of ourselves as part of the biosphere.

The silence of the universe is not a verdict but the clearest reminder of the need for internal due diligence — thorough preliminary self-assessment — before embarking on the most ambitious project in human history.

A Model of Hypothetical Psychological Transition:

If the universe is silent, maybe the problem is not out there, but in how we listen — and in who we believe ourselves to be?

Chapter 4. Cosmos as Harmony

“Your civilization is deaf,” the cosmos might say to us. Not because it is silent, but because we fail to hear its fundamental tone — Harmony.

From the author: In this chapter, I invite you to deliberately change the lens: to look at humanity and the cosmos through the prism of harmony, resonance, and interconnected networks — not as a substitute for rigorous analysis, but as a supporting language that lets us glimpse the shared principles by which an orchestra, a forest, and a civilization can all operate.

Sixty years of silence from space can be interpreted in many ways. But if we treat this silence not as emptiness but as a pause in a dialogue, it takes on a new meaning: perhaps what matters most is not the radio signal itself, but our ability to tune civilization into a particular “mode of listening” to the Universe.

In the science of complex systems, metaphors of resonance and networks are often used to describe how individual elements assemble into a whole — from neural ensembles to ecosystems and social structures.

As early as Pythagoras, we were invited to see the world as a form of harmony governed by simple yet strict numerical ratios [31].

The same proportions that make musical intervals consonant, he applied to the heavenly bodies and their motions. This is how the idea of musica universalis — the “music of the Universe,” a soundless yet mathematically ordered cosmos — was born [31].

Kepler made this image almost experimental: he calculated the ratios of the planets’ orbital speeds and described them as intervals and harmonies.

In effect, he claimed that the cosmos has its own “score,” one that can be read in numbers [32].

For those of us living on the threshold of the Great Filter, this image contains a straightforward lesson. Either a civilization tunes its systems to this underlying order, or it runs the risk that such deafness will, over time, erode its long-term future as a species.

Inner Musical Cosmos: Mozart as a Model of Tuning

In Mozart, cosmic harmony seems to turn inward, into the human being. His ability to hold entire compositions in his mind, to hear all the voices at once, and then to write out the score rapidly becomes a metaphor for the kind of systemic thinking our fragmented civilization so badly lacks: the capacity to hear not only individual parts, but also the whole in which they are brought into accord with one another.

Modern music theory refers to this as audiation — a highly developed inner hearing [33].

For us, this becomes a model of how a complex system is first assembled inwardly — as something whole, clear, and harmonious — and only then realized in the world in the form of laws, constitutions, or strategies.

Practically, this means that stable social structures must first be calibrated internally — at the level of values and goals — before they can endure in the long term.

Tesla and Engineering Harmony: The Brain as Receiver

Tesla did with technology what Mozart did with music. He first constructed his devices as mental models, building a detailed three-dimensional structure in his mind, “running” it, tracking its vibrations, and only then moving on to a physical prototype [34].

In his own description of the process, there is no fundamental boundary between the laboratory and the inner simulation.

His famous line “My brain is only a receiver” evokes the image of an inner antenna tuned to a deeper layer of reality. In Tesla’s engineering worldview, harmony appears as the resonance of fields and forms [34].

In contemporary terms, this raises a question about the quality of our technological creativity. When a society treats its technologies as if they existed in a vacuum, it risks tuning its machines to the very frequencies of its own disintegration.

The Living World as a Network of Signals: From Forests to Civilizations

Modern research shows that the ability to exchange meaningful information is not a human monopoly. Forests linked by mycorrhizal fungal networks add another level: through the mycelium, trees exchange resources and chemical stress signals, and the network begins to function like a nervous system for the ecosystem [35].

For politics and economics, this implies a radical shift. The global system is also a field of signals, where money and armies are only the visible tip of the iceberg, while the invisible part consists of trust, fear, reputation, and shared collective images of the future [36].

This communication network can either stabilize a civilization or set off chain reactions of panic and escalation. In this way, local manifestations of the Great Filter may take shape.

Inner Antennas and the Great Filter: What Is Required of a Civilization

The Great Filter is not only an astronomical puzzle but also a mirror of our institutions and decisions. If most civilizations “go deaf,” it means that at some point their technologies begin to grow faster than their ability to see the consequences: power outpaces ethics, and the speed of information outpaces the depth of understanding.

In this regime, the inner antennas — attention, empathy, the capacity for honest self-reflection — become overloaded with noise. They lose the ability to distinguish genuine risk signals from background chatter.

For a civilization, this translates into a simple task: to learn to look both inward and outward at the same time. It must cultivate inner listening and design its technologies so that they do not drown out these capacities, but amplify them instead.

Plato, Harmony, and a Civilization’s Choice

Plato spoke of harmony as a form of concord, a state of inner and outer agreement rather than mere absence of conflict [37].

From Plato’s logic follows a hard demand: you cannot “tune” to harmony something whose very architecture is built as a war of parts.

When reason systematically suppresses emotion, elites suppress society, and economies suppress ecological limits, this is not a conflict that can be reconciled but a structural dissonance; amplified by technological “antennas,” such arrangements start generating ever-growing noise and instability.

In this sense, the perspective of “Eonatrics” you propose extends and radicalizes the Platonic motif: a civilization that does not seek greater alignment with its own “soul” and the living world reinforces the very mechanisms that make it a candidate for elimination by the Great Filter.

The thesis about institutional frequencies thus gains a rigorous content: institutions can be designed so that their normal mode of operation increases the likelihood of major crises (through false incentives, underestimated complexity, and amplified externalities), instead of damping systemic risks.

And so the thesis about institutional frequencies acquires a precise, substantive meaning: institutions can be designed in such a way that their normal mode of operation increases the likelihood of major crises (through false incentives, underestimation of complexity, and the amplification of externalities) instead of damping systemic risks.

Our choice in the twenty-first century can be formulated in almost technical terms. Either we consciously tune our inner antennas, or we remain deaf in a cosmos that has always been speaking to us — through the music of the spheres, forest networks, the crises of our markets, and the faint signals of our own conscience.

It is to a detailed analysis of this choice — between tuning and deafness — that we now turn in the next part.

Part II. The Great Filter: Humanity at a Crossroads

What is more terrifying: to remain alone forever, or to be heard? Before we shout “We are here!”, we must decide who this “we” is. Our earthly quarrels are children’s squabbles on the threshold of a stellar council. The protocol for a first encounter does not begin with broadcasting our coordinates, but with an attempt to write a shared story of our species that we would not be ashamed to present.

Chapter 5. Are the Odds Stacked Against Us?

Statistics suggest that the chances of survival for a civilization like ours are close to zero. But what if these numbers are not a sentence, but an instruction for how to be saved?

The previous chapters have left us in a strange position. On the one hand, the Universe is full of stars and planets. We have reasonable estimates of how many worlds with suitable conditions there might be in our galaxy. We have sixty years of searching for signals. On the other hand, we still do not see a single civilization that has reached the level of a “cosmic neighbor.”

This asymmetry — between the enormous number of chances and the almost zero number of visible results — is the entry point to the idea that Robin Hanson called the Great Filter.

What Is the Great Filter: From Statistics to Mechanism

The Great Filter is not a single solid wall in one place. It is a chain of stages, each so difficult that most evolutionary lines break off at that point.

In compressed form, Hanson’s formulation is this: if intelligent, long-term cosmic expansion is possible at all, and the Universe has had many “attempts” to launch it, yet we do not see a single other advanced civilization, then for any piece of dead matter the chance of traversing the full path from “stone” to “deep space” is astronomically small [12].

Somewhere between atoms, first cells, complex life, intelligence, and a civilization capable of reliably spreading through the galaxy, there is a hidden sequence of steps that almost no one manages to complete.

The main question of this chapter is therefore: “How far along this Filter have we already come — and how many deadly segments still lie ahead? And more importantly — what drives these ‘deadly segments’: external circumstances, or something encoded in ourselves?”

A Ladder of Improbabilities

Let us try to break down the path from a “dead planet” to a “galactic civilization” into several key rungs.

1. A suitable planet with conditions for complex chemistry and a stable environment.

2. The emergence of the simplest forms of life.

3. The appearance of complex cells (eukaryotes).

4. The formation of complex multicellular life.

5. The rise of intelligent beings capable of building a civilization and a complex culture.

6. The emergence of a technological civilization that is detectable from space.

7. The transition to a stable, long-term civilization capable of not destroying itself with its own technologies and conflicts (reprogramming the “pack logic” toward planetary responsibility).

8. Cosmic synthesis — aligning the development of civilization with the broader laws of the Universe, moving from colonization to creative co-creation.

The fact that we do not see clear traces of steps 7–8 means that either almost no one reaches them, or those who do act in a fundamentally different way.

Two Possibilities: Is the Filter Behind Us or Ahead?

The idea of the Great Filter turns the question “Are we alone?” into a sharper one: “Where exactly is its densest part — behind us, or still ahead of us?”

First possibility: the Great Filter lies behind us. In this case, the emergence of life, the transition to complex cells, or the appearance of intelligence are exceptionally rare events. We have already passed the most dangerous stretch. The silence is not a threat, but a confirmation of our uniqueness. This is an optimistic, but passive, scenario.

Second possibility: the Great Filter lies ahead of us. Here, the early steps occur relatively often, but almost all civilizations crash against the phase of their own technologies and conflicts. The silence means not “we are unique,” but “almost no one has survived long enough to become noticeable, and the reason lies within themselves.” This is a pessimistic, but mobilizing, scenario: the toughest exam — the exam in self-restraint — has not yet begun.

Where Might the Main Filter Be Hiding? A New Hypothesis

A growing body of data leads some researchers to treat the second possibility as the more likely one: planets are common, and life, judging by its early appearance on Earth, may not be especially rare.

If we accept these assumptions, then the Great Filter shifts much closer to us — toward stages 6 and 7.

What makes these stages so deadly? The answer proposed in this book lies not in astrophysics, but in biology and psychology.

The Filter may be the inner conflict of a species that has attained technological power but has not outgrown its evolutionary inheritance. This is the conflict between an ancient pattern — what we will call here the “pack logic,” a set of instincts optimized for the survival of a small group through competition, hierarchy, and division into “us” and “them” — and the new demands of planetary-scale cooperation, long-term planning, and global responsibility.

The main bottleneck, therefore, may turn out not to be technological or astrophysical, but ethical and psychological.

Every microbe we discover in the Universe, while delighting biologists, will be an indirect pointer toward this hypothesis: if life arises easily, then the Great Filter is likely to be an inner crisis of the species rather than an external stroke of bad luck.

The Great Filter as a Test of Wisdom

From this perspective, the parameter L in the Drake equation — the average lifetime of a technological civilization — becomes not an integral over our engineering achievements, but over our ability to recognize and reconfigure our own deepest programs [5; 23].

If the Filter really lies ahead of us, it does not look like a single cataclysm, but like a systemic crisis born of the mismatch between the power of our tools and the archaic nature of our social instincts. Problems accumulate faster than we can resolve them because our collective mind and our institutions still largely operate according to templates designed for life on the savanna, not for managing a nuclear arsenal or a global ecosystem.

The key question, then, becomes: “Can we become a civilization that not only solves problems, but also becomes aware of, rewrites, and harmonizes its own basic survival algorithms”?

This is no longer about physics or statistics. It is about a species’ ability to become a Continuous Witness — a function that keeps long-term consequences and the interests of the whole within its field of view.

Interim Conclusion: Possibility and Responsibility

The Great Filter is a concept that says: somewhere along the chain from “atoms” to a “galactic civilization” there are steps that almost no one manages to pass. The very fact that we have already reached the level of a global technosphere and are able to reflect on this is, in itself, an extraordinary stroke of luck.

The silence of the surrounding cosmos means that either we have already passed most of the Filter, or we are entering its densest region — the region where what is being tested is not our intelligence, but our wisdom and integrity.

Both possibilities offer not only fear, but also meaning:

1. If the Filter lies behind us, we are a rare miracle, and our task is not to squander this chance and not to become the authors of our own filter.

2. If the Filter lies ahead of us, we are one of the few species that has the opportunity to understand its nature and attempt to pass through it.

In both cases, the basic formula is the same: the statistics may not be on our side. But the choice — whether we can rise above the “pack logic” and act as a civilization worthy of its Aeon — remains ours.

In the next chapter, this abstraction will come down to the level of concrete reality: to our current position at a bifurcation point where our ancient psychology meets planetary-scale risks.

Chapter 6. Where Do We Sit in the Statistics?

Metaphorically speaking: “Humanity today is a teenager with the keys to a nuclear reactor. Our brain is tuned for tribal squabbling, yet in our hands lies the fate of a planet. This condition can be described as an acute mismatch of scales.”

This chapter is a direct continuation of the conclusion reached through the concept of the Great Filter in the previous chapter. If the Filter really lies ahead of us, then our current era is not just a historical moment, but a point of systemic tension where ancient psychology collides with planetary responsibility.

Three Trends Shaping the Contemporary Crisis

Modern civilization combines unprecedented technologies with institutions and cognitive patterns that were formed under entirely different conditions. This is not a flaw, but an evolutionary imbalance — a gap between the accelerating pace of technological progress and the much slower rates of social and ethical adaptation. Three interrelated trends illustrate this tension with particular clarity.

1. Powerful technologies, weak control mechanisms

Nuclear weapons emerged in the hands of a species whose brain evolved to assess danger in terms of a neighboring tribe, not in terms of mutual assured destruction. Research in evolutionary psychology and social neuroscience suggests that our core mechanisms for assessing risk and conflict remain largely calibrated to life in small, face-to-face groups [15] [38].

Digital networks now connect billions of people, yet social media often amplifies ancient mechanisms of gossip and the moral expulsion of the “outsider,” turning them into global waves of information and outrage [39].

AI and biotechnology are advancing faster than society can establish stable institutions of oversight and coherent ethical frameworks, which leaves a persistent risk that they will simply be integrated into familiar competitive and hierarchical patterns of power [40] [15].

2. Short planning horizons versus long-term cycles

A growing body of research indicates that, on average, people tend to overweight immediate rewards and underweight long-term consequences — a phenomenon known as time discounting or present bias [41] [30].

This tendency shows up not only in individual choices, but also in our collective institutions: political and economic cycles in many countries rarely extend beyond a few years, reinforcing a focus on short-term outcomes [41].

As a result, this evolutionarily understandable collective “shortsightedness” collides with climate change and technological risks that unfold over timescales of decades and even centuries [42]. As scholars of global governance point out, this kind of institutional myopia makes it much harder to act against slow-moving but potentially catastrophic threats [43].

3. Fragmentation in the face of planetary risks

Many major global risks — from climate collapse to pandemics and AI catastrophes — are transboundary and indivisible by their very nature: their consequences do not respect national borders. Yet the key tools for managing them are distributed across nearly two hundred sovereign states locked in a mix of competition and only limited cooperation [44].

Such a situation is often described as a fragmented system of global governance [43].

Within this book, this is interpreted as one possible effect of “scaling up” group-level logic to the level of nation-states, while the mechanisms of genuinely global cooperation — for which we lack direct evolutionary analogues — remain relatively weak and under-institutionalized [15].

Our Chances: A Perspective on Risks and Potential

According to leading researchers on global catastrophic risk, the probability of severe upheavals in this century does not appear to be negligibly small [45] [46].

Current developments are therefore increasingly described not as a stable plateau, but as a crossroads at which decisions taken over the coming decades will largely determine the shape of humanity’s future trajectory [47].

There are also significant strengths, the most important of which is our unprecedented capacity for reflection:

1. Capacity to recognize the Great Filter and our own nature. For the first time in history, we are not only acting on our internal “programs,” but can also read their source code — in myths, in neuroscience, and in genetics. This allows us to ask: which of our reactions are an obsolete bug, and which are a feature we may need for the future?

2. The age of accelerated technologies as tool and test. Technologies can help us identify emerging risks early and, crucially, design new environments — institutions, digital platforms, urban spaces. These environments must not merely amplify old patterns, but function as a kind of “training ground” that broadens our circle of empathy and cultivates long-term thinking.

3. We are living relatively early. If intelligent species in the cosmos are only beginning to emerge, our situation can be seen as one of the first tests of whether a civilization can navigate a particularly dangerous stretch of its trajectory. In this book, humanity is thus treated — metaphorically — as an experiment in overcoming an internal Filter, rather than as a case already closed with a final verdict.

An Exam in Maturity: Three Questions

If we understand the Great Filter as a kind of exam in collective thinking, we can compress it into three key, though not exhaustive, questions.

1. To what extent are we capable of seeing ourselves not merely as a collection of competing groups and nation-states, but also as a single species bound together by shared long-term conditions of life on one planet?

2. Can we build institutions and practices that take into account not only the interests of the next few years and the current generation, but also the consequences for those who will live decades and centuries from now?

3. Are we able to steer technological development in ways that enhance collective intelligence, empathy, and depth of understanding, rather than serving only our comfort, consumption speed, and competitive efficiency?

A Statistical Paradox of Our Situation

Today, humanity is in the statistically unusual position of being, at the same time:

1. The only known technological civilization in our observable surroundings.

2. Quite plausibly a “typical” example of a species passing through a dangerous transitional phase, if we interpret our situation through the lens of the Great Filter.

3. And, at the same time, the first species we know of that possesses tools for systematic self-knowledge — and, potentially, for rewriting its own fatal scripts.

Бесплатный фрагмент закончился.

Купите книгу, чтобы продолжить чтение.