Бесплатный фрагмент - English for Psychotherapy and Counselling: Handbook for Practitioners

Английский для психотерапии и консультирования: практическое руководство

Предисловие

Дорогой читатель, добро пожаловать на страницы этой книги!

Скажу несколько слов, прежде чем перейдем к основной части.

В психологию меня привела моя первая профессия — лингвистика. В прошлом я работала преподавателем и переводчиком английского языка и однажды решила перевести с английского книгу для друзей-психологов, которая была им очень нужна. Впрочем, психологией я увлекалась задолго до этого. Конечно, хотелось понять себя, других и как это все устроено. Однако именно спортивный интерес при переводе поспособствовал тому, что через время я пошла обучаться на психолога-консультанта, преподавателя психологии, а позже — на клинического психолога. Практиковать начала еще во время учебы, и с тех пор психология окончательно стала моей основной сферой деятельности. Собственно, тогда же, когда я проштудировала существующие учебные материалы по английскому для психологов, у меня зародилась идея о создании учебника, пособия или глоссария. Не хватало практикоориентированных материалов, особенно с учетом огромного количества терминов в области психологии и психотерапии, пришедших из англоязычного контекста, и с учетом большого числа непереведенных на русский язык книг психотерапевтической тематики.

Давайте рассмотрим подробнее структуру этой книги и для кого и чем она будет полезна.

Структура

В книге 10 юнитов (или 10 глав). Каждый юнит состоит из следующих секций:

Lead-in — вводная секция, где вы активизируете свои знания, знакомитесь с ключевой темой и настраиваетесь на работу в рамках юнита.

Reading — профессионально ориентированный текст с аутентичной лексикой и примерами.

Vocabulary — работа с ключевыми терминами, выражениями и профессиональными словосочетаниями, необходимыми для понимания и ведения профессионального диалога.

Grammar Focus — изучение грамматических конструкций на материале профессиональных тем, с акцентом на формы и структуры, часто используемые в психотерапевтической практике.

Communication — практика коммуникативных навыков: анализ и разыгрывание типичных профессиональных диалогов, ситуаций из сессий и интервью, развитие языковой гибкости.

Professional Practice — применение изученных структур и терминов в практических заданиях: самопрезентация, описание случаев, упражнения для закрепления профессионального языка.

Vocabulary and Collocations — подборка ключевой лексики юнита и профессиональных устойчивых оборотов с переводом на русский язык для быстрого повторения и удобного использования в работе.

Руководство предназначено для специалистов с уровнем английского языка B1–B2 (Intermediate — Upper-Intermediate). Однако благодаря подробным справочным материалам и структурированной подаче знакомой профессиональной тематики руководство будет интересно также специалистам с уровнем английского A-2 (Pre-Intermediate).

Руководство построено на принципе i+1 (comprehensible input) Стивена Крашена: вы встречаете языковой материал чуть выше текущего уровня, что стимулирует естественное языковое развитие.

Тексты в секции Reading содержат более сложную грамматику и разнообразные структуры, чем изучаемые в секции Grammar Focus. Вы встречаете новые языковые явления в профессиональном контексте, где они понятны благодаря знакомой профессиональной тематике, ключевой лексике из Vocabulary, контексту и предварительной работе в Lead-in.

Руководство следует коммуникативной методике (Communicative Approach), которая лежит в основе всех современных аутентичных курсов английского языка, таких как Headway, New English File, Total English. Это означает, что все материалы юнитов — тексты, задания, инструкции и упражнения — представлены исключительно на английском языке, что создает эффект языкового погружения и помогает развивать способность думать на английском без мысленного перевода. В структуре самого руководства русский язык используется в секции Vocabulary and Collocations в конце каждого юнита, а также в приложениях.

Представленные задания и упражнения могут быть использованы как для групповой, так и для самостоятельной работы.

В конце руководства вы также найдете четыре приложения, которые служат справочными материалами для самостоятельной работы и практики:

Appendix 1. Vocabulary and Collocations — полный список ключевой профессиональной лексики и устойчивых словосочетаний по теме конкретного юнита с переводом на русский язык. Используйте это приложение для быстрого поиска терминов и повторения материала.

Appendix 2. Grammar Reference — справочник по грамматическим темам, изученным в руководстве, с правилами и примерами из профессиональных контекстов. Обращайтесь к нему при выполнении заданий или для систематизации грамматических знаний.

Appendix 3. Therapist’s Phrasebook — набор готовых профессиональных фраз и выражений для различных ситуаций и контекстов в терапевтической практике: от начала сессии до работы с сопротивлением клиента. Есть перевод на русский язык. Этот разговорник поможет вам почувствовать себя увереннее в реальной коммуникации.

Appendix 4. Protocols — образцы протоколов терапевтических сессий с примерами формулировок для документирования работы с клиентами в соответствии с международными стандартами.

Какие задачи поможет решить это руководство?

Это руководство поможет психологу-консультанту, психотерапевту, клиническому психологу решить следующие практические задачи:

В работе с клиентами*:

• Провести первичную консультацию (intake interview) на английском языке

• Собрать анамнез и задать диагностические вопросы с использованием точной профессиональной лексики

• Объяснить клиенту суть терапевтического подхода и техник на понятном английском

• Выстроить терапевтические границы и обсудить условия работы

• Вести протоколы сессий и документировать случаи по международным стандартам

ㅤ

В профессиональном развитии:

• Читать актуальные исследования и профессиональную литературу в оригинале

• Участвовать в англоязычных супервизиях и получать обратную связь от зарубежных коллег

• Представлять клинические случаи (case presentations) на профессиональных встречах

• Участвовать в международных конференциях, семинарах и тренингах

• Проходить дополнительное обучение у международных специалистов без языкового барьера

В повседневной практике:

• Использовать готовые профессиональные фразы для важных моментов сессии (эмпатия, конфронтация, завершение)

• Применять со знанием дела специализированную терминологию психодинамического, когнитивно-поведенческого и экзистенциально-гуманистического подходов

• Понимать культурные особенности профессиональной коммуникации с англоязычными клиентами и коллегами

* Здесь и далее мы будем использовать именно термин “клиент”, а не “пациент”. В англоязычной практике термин “клиент” является общепринятым в консультировании и большинстве направлений психотерапии. Клиент — это активный участник терапевтического процесса, в котором отношения строятся на принципах партнерства и сотрудничества. Поскольку цель руководства – подготовить вас к работе в международной среде, мы будем придерживаться этой терминологической нормы

Для кого будет полезна эта книга?

ㅤ

Практикующие специалисты:

• Психотерапевты и психологи-консультанты, планирующие работать с англоязычными клиентами

• Консультанты, переехавшие в англоязычные страны или работающие онлайн с международной аудиторией

• Клинические психологи, желающие расширить свою практику на англоязычный рынок

• Специалисты, проходящие сертификацию или супервизию у зарубежных коллег

Студенты и обучающиеся:

• Студенты психологических и психотерапевтических программ, готовящиеся к стажировкам за рубежом

• Слушатели программ переподготовки по психотерапии с намерением практиковать на английском

• Психологи, поступающие на магистерские или аспирантские программы в англоязычных университетах

Исследователи и преподаватели:

• Преподаватели психологии, ведущие занятия на английском языке

• Исследователи, публикующие работы в международных журналах

• Специалисты, участвующие в международных конференциях и научных обменах

Специалисты смежных областей:

• Коучи, работающие с психологическими аспектами развития личности

• Специалисты по ментальному здоровью в международных организациях

С большой благодарностью всем моим учителям и близким, которые поддерживали меня на этом пути!

Приятного изучения!

UNIT 1.

INTRODUCTION TO PSYCHOTHERAPY

LEAD-IN:

Mental Health Professionals and Their Roles

Activity 1: What Do You Know?

Look at the list of mental health professionals below and think about the questions:

Mental health professionals:

• Clinical psychologist

• Psychiatrist

• Counselling psychologist

• Psychotherapist

Think about:

• What do you know about each professional? What do they do?

• How are they different? (education, methods, types of problems)

• Which specialist would you recommend for: anxiety, depression, relationship issues, serious mental illness?

Activity 2: Vocabulary brainstorm

Work in small groups. You have 3 minutes to write down as many words as you can related to mental health and therapy.

Example: therapy, counselling, treatment, session, assessment, diagnosis…

Activity 3: Discussion questions

Discuss these questions with your partner:

1. What comes to mind when you hear the word “psychotherapy”?

2. Do you think psychotherapy is different from psychology? How?

3. What do psychotherapists do?

4. What is the difference between a clinical psychologist and other psychologists?

5. Why do people go to therapy?

6. Are there different types of psychotherapy? What do you know about them?

Key vocabulary for this unit:

Match the words with their definitions:

1. Psychology

2. Counselling

3. Psychotherapy

4. Psychiatry

5. Mental health

6. Clinical psychology

a) Medical specialty dealing with diagnosis and treatment of mental disorders

b) The scientific study of the mind and behaviour

c) Treatment using psychological methods through regular interaction

d) Professional guidance to help people cope with specific problems

e) A person’s condition regarding their psychological and emotional well-being

f) Branch of psychology focused on assessment and treatment of mental health disorders

READING:

Mental Health Professionals: Who Does What?

Pre-reading task

Before you read, discuss:

1. What do you think is the main difference between these four professions?

2. What does a clinical psychologist do that other psychologists might not do?

3. Which profession requires medical training?

4. Which focuses on short-term problems?

ㅤ

Mental Health Professionals: Who Does What?

When people experience emotional difficulties, mental health problems, or simply want to understand themselves better, they often wonder: “Who should I see?” The field of mental health includes several types of professionals, and while their work overlaps, there are important distinctions between them.

Psychology is the scientific study of the mind, behaviour, and mental processes. Psychologists are trained professionals who typically hold a doctoral degree (PhD or PsyD) in psychology. They use evidence-based methods to assess, diagnose, and treat mental health conditions. Unlike psychiatrists, psychologists in most countries do not prescribe medication; instead, they focus on psychological interventions and therapy.

Clinical Psychology is a specialized branch of psychology that focuses on the assessment, diagnosis, and treatment of mental health disorders and psychological distress. Clinical psychologists work with individuals, couples, families, and groups to address a wide range of psychological issues, from mild adjustment problems to severe mental disorders such as schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, and severe depression.

What makes clinical psychologists unique is their extensive training in psychological assessment. They are skilled in using various assessment tools, including clinical interviews, behavioural observations, and standardized psychometric tests. A clinical psychologist conducts comprehensive psychological evaluations to understand the nature and severity of a client’s difficulties, considering biological, psychological, and social factors.

Clinical psychologists provide evidence-based psychological therapies and interventions. They work in diverse settings including hospitals, mental health clinics, rehabilitation centers, private practices, universities, and research institutions. Many clinical psychologists also conduct research to develop new treatments and improve existing interventions. Additionally, they often supervise other mental health professionals and contribute to training programs.

The work of a clinical psychologist typically involves:

• Conducting detailed psychological assessments and diagnostic evaluations

• Developing individualized treatment plans based on assessment findings

• Providing various forms of psychotherapy (CBT, psychodynamic, family therapy, etc.)

• Monitoring client progress and adjusting treatment as needed

• Working collaboratively with other healthcare professionals

• Conducting applied research and contributing to evidence-based practice

• Providing clinical supervision to trainees and other professionals

Counselling Psychology is another branch of psychology that shares some similarities with clinical psychology but has a different focus. Counselling psychologists typically work with clients experiencing less severe psychological distress and focus more on personal development, life transitions, and adjustment issues. While clinical psychologists often work with severe psychopathology, counselling psychologists emphasize wellness, growth, and helping people function better in their daily lives.

Counselling (as a profession distinct from counselling psychology) is a helping profession that focuses on specific problems or life transitions. Counsellors, who usually have a master’s degree in counselling or a related field, help clients cope with immediate issues such as career decisions, academic stress, grief, or relationship conflicts. Counselling is typically shorter-term than psychotherapy and more solution-focused. It emphasizes practical coping strategies and goals rather than deep exploration of underlying emotional patterns.

Psychotherapy, often called talk therapy, is a treatment intervention that uses psychological methods through regular personal interaction to help people change behaviour, increase well-being, and overcome problems. While clinical psychologists, counselling psychologists, and counsellors may all provide psychotherapy, the term “psychotherapist” often refers to professionals who engage in more in-depth, long-term therapeutic work. Psychotherapy explores deeper emotional issues, past experiences, and unconscious patterns that influence present behaviour.

Psychiatry is a medical specialty focused on the diagnosis, treatment, and prevention of mental, emotional, and behavioural disorders. Psychiatrists are medical doctors (MDs) who complete medical school followed by specialized training in psychiatry. Because of their medical background, psychiatrists can prescribe medication and may use biological treatments. While some psychiatrists provide psychotherapy, many focus primarily on medication management, especially in contemporary practice where they often work collaboratively with clinical psychologists and other therapists.

Three Main Approaches in Psychotherapy

Within psychotherapy (practised by clinical psychologists and other therapists), three major theoretical approaches have shaped modern practice:

Cognitive-Behavioural Therapy (CBT) is a structured, goal-oriented approach that focuses on the connection between thoughts, feelings, and behaviours. CBT therapists help clients identify negative automatic thoughts and cognitive distortions, then work to challenge and change these patterns. This approach is typically short-term and emphasizes practical homework assignments and skills development. CBT has strong research support for treating anxiety, depression, and many other conditions. Clinical psychologists often use CBT because of its evidence-based effectiveness.

Psychodynamic Therapy has its roots in psychoanalytic theory and emphasizes the role of unconscious processes, early childhood experiences, and relationship patterns. Psychodynamic therapists explore how past experiences shape current behaviour and help clients gain insight into recurring patterns. This approach pays particular attention to the therapeutic relationship itself, including transference (when clients project feelings onto the therapist) and countertransference (the therapist’s emotional reactions to the client). Psychodynamic therapy is usually longer-term than CBT and is often used by clinical psychologists working with complex personality issues and trauma.

Existential-Humanistic Therapy emphasizes personal growth, self-actualization, and the client’s inherent capacity for healing. This approach, which includes person-centered therapy and Gestalt therapy, focuses on the here-and-now experience, authenticity, and the therapeutic relationship. Humanistic therapists provide unconditional positive regard, empathy, and congruence, creating a safe space where clients can explore their feelings and develop self-awareness. Rather than directive techniques, this approach follows the client’s lead and trusts their inner wisdom.

Each approach has its strengths, and many modern clinical psychologists and therapists integrate elements from different schools of thought, practising what is called “integrative” or “eclectic” therapy. The choice of approach often depends on the client’s needs, the assessment findings, and the nature of their difficulties.

Comprehension questions:

1. What is the main educational difference between psychologists and psychiatrists?

2. What makes clinical psychology different from other branches of psychology?

3. According to the text, how does counselling differ from psychotherapy in terms of focus and duration?

4. What is the difference between clinical psychology and counselling psychology?

5. Which professional can prescribe medication? Why?

6. What are the three main approaches to psychotherapy mentioned in the text?

7. Which therapeutic approach focuses on thoughts, feelings, and behaviours?

8. What does “transference” mean in psychodynamic therapy?

9. Which approach emphasizes personal growth and self-actualization? ㅤ

VOCABULARY:

Professional Terminology and Collocations

A. Find words in the text that match these definitions:

1. Based on scientific research and proven methods

(paragraph 2): _______

2. A wide range of psychological issues and conditions that clinical psychologists assess (paragraph 3): _______

3. A complete evaluation of someone’s psychological condition (paragraph 4): _______

4. Tests that measure psychological variables like intelligence or personality (paragraph 4): _______

5. Concentrating on finding practical answers to current problems (paragraph 7): _______

6. Mental processes that happen without our awareness (paragraph 11): _______

7. Inborn, natural, existing from birth (paragraph 12): _______

8. Being genuine and true to oneself (paragraph 12): _______

B. Complete the collocations from the text. More than one answer may be possible:

1. mental health _______

2. psychological _______

3. evidence-_______ methods

4. _______ plans

5. _______ strategies

6. therapeutic _______

7. clinical _______

8. automatic _______

9. personal _______

10. assessment _______

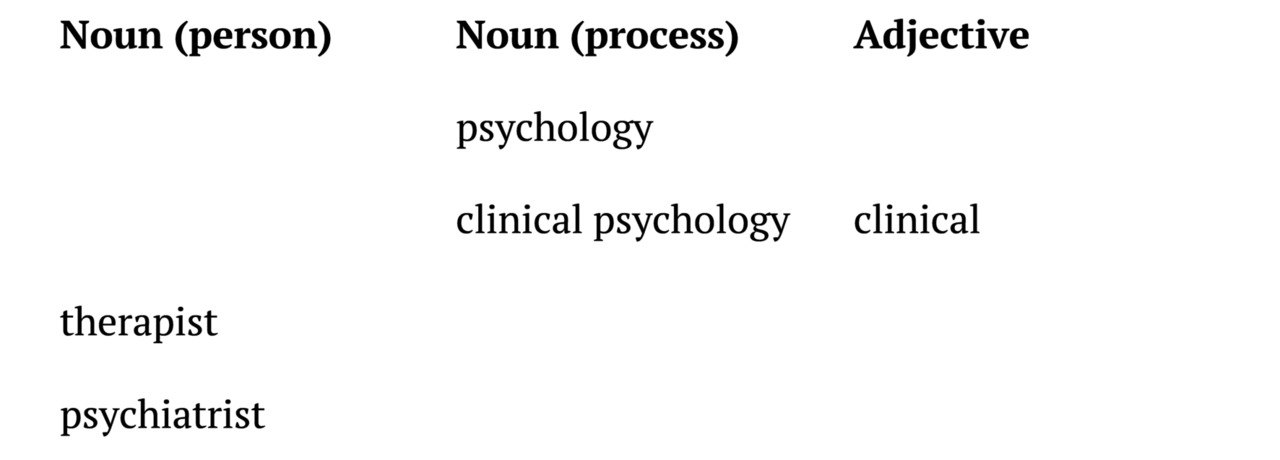

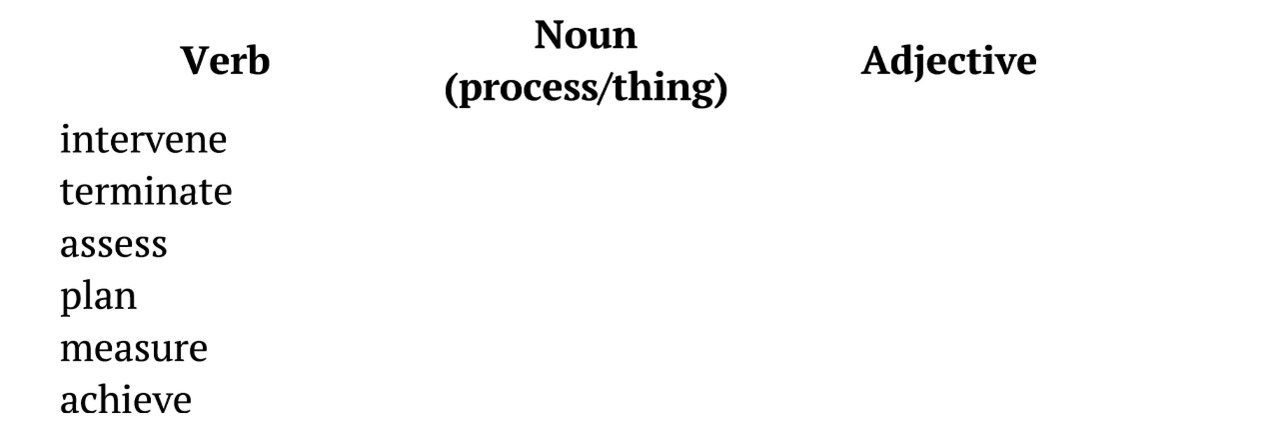

C. Word families

Complete the table:

Discussion questions:

1. In your country, which mental health professional do people usually consult first?

2. What is the role of clinical psychologists in your healthcare system?

3. Do you think the distinctions between these professions are clear in your language?

4. Which therapeutic approach appeals to you most? Why?

5. Should all clinical psychologists be trained in all three approaches, or specialize in one?

6. What are the advantages of seeing a clinical psychologist vs. a psychiatrist?

GRAMMAR FOCUS:

Present Simple for definitions and descriptions / Comparative structures

A. Present Simple for Definitions and Professional Descriptions

We use Present Simple to define concepts and describe what professionals do:

Form:

• Affirmative: Subject + verb (+ s/es for he/she/it)

• Negative: Subject + don’t/doesn’t + main verb

• Questions: Do/Does + subject + main verb?

ㅤ

Examples from Psychology:

• Psychology studies human behaviour and mental processes.

• Clinical psychologists assess and treat mental health disorders.

• Psychotherapists help clients manage emotional difficulties.

• A psychiatrist prescribes medication for mental health conditions.

• Counselling focuses on specific life problems.

ㅤ

Exercise 1: Complete the sentences

Use the correct form of the verb in brackets:

1. Clinical psychologists _______ (assess) mental health conditions using psychometric tests.

2. Psychotherapy _______ (involve) regular communication between therapist and client.

3. Clinical psychologists _______ (not prescribe) medication.

4. _______ (do) clinical psychologists conduct research? Yes, many of them _______ (do).

5. Humanistic therapy _______ (emphasize) personal growth and self-actualization.

6. A counselling psychologist _______ (focus) more on life transitions than severe pathology.

B. Comparative Structures

We use comparative structures to show differences and similarities between concepts:

ㅤ

Structures:

• as + adjective + as (equally)

• more/less + adjective + than

• adjective + -er + than

Examples from Psychology:

• Psychotherapy is more intensive than counselling.

• Clinical psychology is as important as psychiatry in mental healthcare.

• Psychoanalysis is less directive than CBT.

• Clinical psychology training is longer than counselling psychology training.

ㅤ

Exercise 2: Compare the professionals

Complete the sentences using comparative structures:

1. A psychiatrist’s training is _______ (long) than a clinical psychologist’s.

2. Clinical psychologists typically work with _______ (severe) mental health problems than counselling psychologists.

3. A clinical psychologist’s assessment is _______ (detailed) than a counsellor’s initial interview.

4. Counselling sessions are usually _______ (short) than psychotherapy sessions.

5. Clinical psychology is not _______ (medical) as psychiatry.

6. Psychotherapy can be _______ (effective) than medication for some conditions.

7. Clinical psychologists do _______ (much) research than general counsellors.

8. Assessment skills are _______ (important) in clinical psychology than in some other areas.

Exercise 3: Correct the mistakes

Find and correct the mistakes in these sentences:

1. A clinical psychologist are working with complex mental health conditions.

2. Psychiatrist training is more longer than counselling training.

3. Does psychiatrists prescribes medication?

4. A psychotherapist don’t just provide therapy; they also works with emotions.

5. Psychological assessment is as important than medication in clinical practice.

6. What a counselling psychologist do during a first session?

7. Clinical psychologists works in hospitals, clinics, and private practice.

8. Is clinical psychology more scientific than counselling psychology?

9. A counsellor are helping clients with mild to moderate difficulties.

10. Psychiatrists is medical doctors who can prescribe medications.

11. Does a psychotherapist needs a doctoral degree?

12. Counselling psychologists provides talk therapy and don’t diagnose conditions.

COMMUNICATION: Understanding Mental Health Professionals: An Interview with Dr. Sarah Mitchell

Participants: Rebecca Williams (Reporter, Mental Health Today Magazine) and Dr. Sarah Mitchell (Clinical Psychologist, Private Practice)

Reporter: Good morning, Dr. Mitchell. Thank you for agreeing to talk with us today. Our readers are often confused about the differences between mental health professionals. Can you help us understand who does what?

Dr. Mitchell: Of course! I’m happy to clarify. It’s a common confusion, and it’s actually quite important to understand the distinctions.

Reporter: Let’s start with psychiatrists. How are they different from psychologists?

Dr. Mitchell: Well, the main difference is their training and what they can do. Psychiatrists are medical doctors. They go to medical school and can prescribe medication. They focus mainly on the biological aspects of mental health — things like brain chemistry and medications that can help with conditions like depression or anxiety.

Reporter: I see. And what about clinical psychologists? That’s your specialty, right?

Dr. Mitchell: Yes, exactly. Clinical psychologists have a doctoral degree in psychology, not medicine. We can’t prescribe medication, but we’re trained to diagnose mental health conditions and provide therapy. We also do psychological assessments and testing to understand what’s going on with a person’s mental health.

Reporter: So, you both diagnose, but only psychiatrists prescribe?

Dr. Mitchell: Correct. And I should mention counselling psychologists too. They’re similar to clinical psychologists, but they typically work with less severe issues — like relationship problems, stress management, or life transitions. They focus more on helping people with everyday challenges rather than serious mental disorders.

Reporter: That’s helpful. What about psychotherapists? Where do they fit in?

Dr. Mitchell: Psychotherapist is actually a more general term. It can include clinical psychologists, counseling psychologists, and other professionals who provide talk therapy. The key is that psychotherapists use various therapeutic approaches to help people change their thoughts, feelings, and behaviours.

Reporter: Speaking of approaches, can you briefly explain the main types of psychotherapy?

Dr. Mitchell: Sure! There are three major approaches we commonly use. The first is psychodynamic therapy, which comes from Freud’s work. It focuses on unconscious thoughts and how our past, especially childhood, experiences affect us today. It’s often long-term therapy.

Reporter: And the second approach?

Dr. Mitchell: That’s cognitive-behavioural therapy, or CBT. This is very popular today because it’s practical and usually shorter. CBT helps people identify negative thought patterns and change them. The idea is that if you change how you think, you’ll change how you feel and behave. It works really well for anxiety and depression.

Reporter: I’ve heard a lot about CBT, and what’s the third approach?

Dr. Mitchell: The third is humanistic therapy, which includes person-centered therapy. This approach believes that everyone has the potential to grow and solve their own problems. The therapist creates a supportive, non-judgmental environment where clients can explore their feelings and find their own solutions. Carl Rogers developed this approach.

Reporter: So different approaches for different people?

Dr. Mitchell: Exactly. Some people benefit more from exploring their past, others need practical strategies they can use right away, and some just need a safe space to figure things out themselves. Many therapists today actually combine approaches based on what each client needs.

Reporter: That makes sense. One last question — if someone is struggling with mental health issues, how do they know which professional to see?

Dr. Mitchell: Good question! If you think you might need medication, start with a psychiatrist. If you want therapy and psychological testing, a clinical psychologist is a good choice. For relationship issues or life stress, a counselling psychologist or counsellor works well. And remember, many people see both a psychiatrist for medication and a psychologist for psychotherapy.

Reporter: Dr. Mitchell, thank you so much for making this clearer for our readers.

Dr. Mitchell: My pleasure. The most important thing is that people get the help they need, no matter which professional they choose!

ㅤ

TASK 1: True / False / Not Mentioned

Instructions: Read the statements below about the interview. Decide if each statement is:

• TRUE (T) – the statement agrees with the information in the interview

• FALSE (F) – the statement contradicts the information in the interview

• NOT MENTIONED (N/M) – the information is not given in the interview

ㅤ

Statements:

1. Psychiatrists go to medical school and can prescribe medication.

2. Clinical psychologists work only in hospitals.

3. CBT is the oldest approach to psychotherapy.

4. Counselling psychologists typically work with serious mental disorders.

5. Dr. Mitchell has a doctoral degree in psychology.

6. Psychotherapist is another name for psychiatrist.

7. Clinical psychologists can do psychological assessments and testing.

8. Dr. Mitchell thinks medication is more effective than therapy.

9. Psychiatrists focus on the biological aspects of mental health.

10. Psychodynamic therapy focuses on childhood experiences and unconscious thoughts.

ㅤ

Task 2: Personal Response

Discuss: which professional would you prefer to see and why? Which therapy approach sounds most interesting to you?

Task 3: Creating a Comparison Chart

Try to create a visual comparison chart of the four professionals (education, what they can do, typical clients/patients, work settings).

PROFESSIONAL PRACTICE:

Self-Introduction as a Psychology Professional

Sample Introductions

ㅤ

Counselling Psychologist

Hello, my name is Sarah Mitchell, and I’m a counselling psychologist. I work with individuals and couples who are experiencing difficulties in their personal relationships or facing challenging life transitions. My approach focuses on helping clients develop coping strategies and build resilience. I specialize in stress management and career counselling. I’ve been practicing for eight years, and I currently work at a community mental health center. I believe in creating a supportive, non-judgmental environment where clients feel comfortable exploring their concerns.

Psychiatrist

Good morning. I’m Dr. James Chen, a psychiatrist at St. Mary’s Hospital. I assess, diagnose, and treat mental health conditions from a medical perspective. My work involves evaluating patients’ symptoms, prescribing medication when appropriate, and monitoring treatment progress. I specialize in mood disorders and anxiety-related conditions. In addition to medication management, I collaborate with psychologists and therapists to ensure comprehensive care for my patients. I completed my medical degree and psychiatric residency at Johns Hopkins University.

Clinical Psychologist

Hi, I’m Dr. Emma Rodriguez. I’m a clinical psychologist specializing in assessment and treatment of psychological disorders. I conduct psychological evaluations, administer diagnostic tests, and provide evidence-based therapy for individuals with various mental health conditions. My areas of expertise include depression, trauma, and personality disorders. I use cognitive-behavioural therapy and psychodynamic approaches in my practice. I work both in private practice and as a consultant at a local psychiatric hospital.

Psychotherapist

Hello, I’m Michael Thompson, a licensed psychotherapist. I provide talk therapy to help people understand their thoughts, feelings, and behaviours. I work with clients dealing with anxiety, relationship issues, and personal growth challenges. My therapeutic approach is integrative, drawing from humanistic and existential traditions. I’ve been in practice for twelve years and currently see clients in both individual and group therapy settings. My goal is to help people gain insight and make meaningful changes in their lives.

ㅤ

Useful Phrases for Self-Presentation

Stating Your Name and Title

• My name is…, and I’m a…

• I’m Dr./Mr./Ms. …, a licensed/qualified…

• You can call me… I work as a…

Describing Your Role

• I specialize in…

• My main focus is…

• I work with clients/patients who…

• My area of expertise is…

• I primarily deal with…

Explaining Your Approach

• I use/practice…

• My approach is based on…

• I combine… with…

• I believe in…

• My therapeutic style is…

Mentioning Your Experience

• I’ve been practising for… years

• I have… years of experience in…

• I completed my training at…

• I previously worked at/as…

Describing Your Work Setting

• I work at/in…

• I’m currently based at…

• I maintain a private practice in…

• I see clients both in… and…

Highlighting Your Goals

• My goal is to help clients…

• I aim to support people in…

• I focus on helping patients…

• I work towards…

ㅤ

Practice Exercises

ㅤ

Exercise 1: Complete Your Introduction

Fill in the blanks with information about yourself to create your own professional introduction.

Hello, my name is __________, and I’m a __________. I work with __________ who are experiencing __________. My approach focuses on __________. I specialize in __________. I’ve been practising/studying for __________, and I currently work/study at __________. I believe in __________.

Exercise 2: Match and Complete

Match the sentence starters with appropriate endings, then write three sentences about yourself.

Sentence starters:

• My main focus is…

• I’ve been practising for…

• My therapeutic approach is based on…

• I work with clients who…

• My goal is to help…

Possible endings:

• ...are struggling with anxiety and stress

• ...cognitive-behavioural principles

• ...supporting people through difficult transitions

• ...five years in various clinical settings

• …working with children and adolescents

Exercise 3: Build Your Introduction (Step-by-Step)

Write one sentence for each category to build your complete introduction:

1. Name and title: _________________________________

2. Who you work with: _________________________________

3. Your specialization: _________________________________

4. Your approach/methods: _________________________________

5. Your experience/education: _________________________________

6. Your workplace: _________________________________

7. Your professional philosophy: ______________________________

ㅤ

Exercise 4: Listening and Note-Taking

Listen to your partner’s introduction and complete the information:

• Name and title: _________________________________

• Specialization: _________________________________

• Type of clients: _________________________________

• Approach/methods: _________________________________

• Experience: _________________________________

• Current workplace: _________________________________

Vocabulary and collocations for Unit 1

psychology — психология

counselling — консультирование

psychotherapy — психотерапия

psychiatry — психиатрия

mental health — психическое здоровье

clinical psychology — клиническая психология

clinical psychologist — клинический психолог

psychiatrist — психиатр

counselling psychologist — психолог-консультант

psychotherapist — психотерапевт

emotional difficulties — эмоциональные трудности

mental health problems — проблемы психического здоровья

mental health professionals — специалисты по психическому здоровью

evidence-based methods — методы, основанные на научных данных

prescribe medication — назначать лекарства

psychological interventions — психологические вмешательства/интервенции

mental health disorders — расстройства психического здоровья

psychological distress — психологический дистресс

adjustment problems — проблемы адаптации

severe mental disorders — тяжелые психические расстройства

psychological assessment — психологическая оценка

assessment tools — инструменты оценки

clinical interview — клиническое интервью

behavioural observations — поведенческие наблюдения

psychometric tests — психометрические тесты

comprehensive psychological evaluation — всесторонняя психологическая оценка

mental health clinics — клиники психического здоровья

rehabilitation centers — реабилитационные центры

private practice — частная практика

treatment plans — планы лечения

assessment findings — результаты оценки

monitor client progress — отслеживать прогресс клиента

adjust treatment — корректировать лечение

healthcare professionals — медицинские специалисты

clinical supervision — клиническая супервизия

personal development — личностное развитие

life transitions — жизненные переходы

adjustment issues — проблемы адаптации

cope with — справляться с

relationship conflicts — конфликты в отношениях

coping strategies — стратегии совладания

solution-focused — ориентированный на решение

underlying emotional patterns — скрытые эмоциональные паттерны

psychological methods — психологические методы

change behaviourehavior — изменить поведение

increase well-being — повысить благополучие

overcome problems — преодолеть проблемы

unconscious patterns — бессознательные паттерны

biological treatments — биологические методы лечения

negative automatic thoughts — негативные автоматические мысли

cognitive distortions — когнитивные искажения

unconscious processes — бессознательные процессы

childhood experiences — детские переживания

relationship patterns — паттерны отношений

gain insight — обрести/получить инсайт

therapeutic relationship — терапевтические отношения

transference — перенос

countertransference — контрперенос

personal growth — личностный рост

self-actualization — самоактуализация

inherent capacity — врожденная способность

unconditional positive regard — безусловное позитивное принятие

self-awareness — самосознание

authenticity — аутентичность

psychopathology — психопатология

mental health condition — состояние психического здоровья

UNIT 2.

FIRST CONTACT AND BUILDING RAPPORT

LEAD-IN:

First Impressions and Creating a Safe Space

Activity 1: First Impressions Matter

Think about your own experiences. Reflect individually for 2 minutes, then share with a partner:

• What makes you feel comfortable when meeting someone new in a professional setting?

• Can you remember a time when someone made you feel welcome immediately? What did they do?

• What might make a person feel nervous about meeting a psychologist for the first time?

• How quickly do you form an impression of a new person? Do first impressions change?

Activity 2: Creating a Safe Space

Work in small groups. Look at these scenarios and discuss: Which therapist behaviours help build trust? Which might create barriers?

Scenario A: The therapist greets the client warmly, offers them a choice of where to sit, and begins by saying, “I’m glad you’re here. Take your time to settle in”.

Scenario B: The therapist immediately starts asking detailed questions about the client’s problems without any introduction.

Scenario C: The therapist explains what will happen in today’s session and checks if the client has any questions before beginning.

Scenario D: The therapist talks extensively about their own qualifications and achievements.

Activity 3: Think-Pair-Share

Think (1 minute): What questions might a client have when they first meet a psychologist?

Pair (3 minutes): Share your ideas with a partner and add to your list.

Share (5 minutes): Groups share with the class. Create a master list on the board.

Key vocabulary for this unit:

Match the words with their definitions:

1. Rapport

2. Therapeutic alliance

3. Confidentiality

4. Boundaries

5. Informed consent

6. Safe space

a) The agreement to protect private information shared in therapy

b) Professional limits that define the therapeutic relationship

c) A trusting connection between therapist and client

d) Permission given by a client after receiving full information about treatment

e) The collaborative relationship between therapist and client working toward goals

f) An environment where a client feels comfortable expressing themselves

READING:

The First Meeting with a Client: Building Trust and Therapeutic Alliance

Pre-reading task

Before you read, discuss with a partner:

1. What do you think happens in the first therapy session?

2. What information should a therapist provide for a new client?

3. How might a client feel during their first meeting with a psychologist?

4. What makes a good first impression in a professional helping relationship?

ㅤ

The First Meeting with a Client: Building Trust and Therapeutic Alliance

The initial therapy session is unlike any other professional encounter. For the client, it often represents a significant step — one that may have taken weeks or months of consideration before they finally picked up the phone to make an appointment. Many clients arrive feeling anxious, uncertain, or vulnerable. They may be wondering: “Will this person understand me? Can they really help? What if I’m judged?” For the therapist, the first session is an opportunity to create a foundation of trust and safety that will support all future therapeutic work.

Creating the Right Environment

The first impression begins before any words are spoken. Research shows that the therapeutic alliance — the collaborative relationship between therapist and client — is often established in the first session and remains stable throughout treatment. This means that what happens in the initial meeting matters tremendously.

When greeting a new client, warmth and professionalism are equally important. A therapist typically welcomes the client in the waiting area, makes eye contact, offers a warm greeting, and invites them to follow to the therapy room. Some therapists offer a brief tour, which helps the client orient themselves and reduces anxiety. Simple gestures like offering the client a choice of where to sit can give them a sense of control and comfort.

The therapy room itself should feel safe and private. Comfortable seating, appropriate lighting, and the absence of distractions all contribute to creating what therapists call a “safe space” — an environment where clients feel they can speak freely.

The Opening Conversation

Once seated, the therapist typically begins by acknowledging that first sessions can feel uncomfortable. A statement like, “I know it can feel strange talking to someone you’ve just met about personal matters. That’s completely normal, and we’ll take things at your pace,” can immediately reduce anxiety.

Before diving into the client’s concerns, the therapist explains what will happen during this first session. This might sound something like: “Today, we have about 50 minutes together. We’ll spend some time going over important information about confidentiality and how therapy works, and then I’d like to hear from you about what brings you here. Do you have any questions before we begin?”

Informed Consent and Confidentiality

A critical component of the first session is discussing informed consent. This isn’t just a legal formality — it’s an ethical cornerstone that empowers clients and establishes transparency. Informed consent means ensuring the client fully understands what they’re agreeing to before therapy begins.

The therapist explains several key elements:

The nature of therapy: What therapy involves, the approaches the therapist uses, and what clients can generally expect from the process.

Confidentiality: Everything discussed in therapy remains private and confidential. This principle is essential because clients need to trust that their information is safe in order to speak openly. However, there are important limits to confidentiality that must be clearly explained:

• If the client is at risk of harming themselves

• If the client is at risk of harming someone else

• If there is suspected abuse or neglect of a child, elderly person, or dependent adult

• If records are subpoenaed by a court

• If the client provides written permission to share information

Most therapists say something like: “What we discuss here is confidential, which means I won’t share this information with anyone without your permission. However, there are a few exceptions where I’m legally required to break confidentiality, particularly if there’s a risk of harm to you or someone else. Does that make sense? Do you have any questions about confidentiality?”

Risks and benefits: while therapy is generally beneficial, it can sometimes be uncomfortable as clients explore difficult emotions or memories. The therapist discusses both potential benefits and any risks.

Practical matters: this includes session frequency, length, fees, cancellation policies, and what to do in case of emergency.

Client rights: clients have the right to ask questions, refuse any intervention, seek a second opinion, and end therapy at any time.

While many therapists provide written consent forms, the verbal discussion is equally important. The therapist should invite questions and check for understanding throughout this explanation.

Establishing Therapeutic Boundaries

Boundaries are the professional limits that define the therapeutic relationship. Clear boundaries create safety and help clients know what to expect. Boundaries are established from the very first contact and are maintained throughout treatment.

Therapeutic boundaries include:

• Session structure (length, frequency, location)

• Contact between sessions (whether clients can call or email, and under what circumstances)

• Social media policies (most therapists maintain strict boundaries around social media connections with clients)

• Physical boundaries (professional, appropriate physical space)

• Role clarity (the therapist is not a friend, but a trained professional providing treatment)

Boundaries are not meant to be cold or distant. Rather, they create a consistent, safe framework within which the therapeutic relationship can develop. Good boundaries actually build trust because clients learn that the therapist is reliable, consistent, and professionally committed to their wellbeing.

Building Rapport

Once the administrative matters are addressed, the therapist invites the client to share their story. This is typically done with an open-ended question such as, “What brings you to therapy at this time?” or “Tell me a bit about what’s been going on for you”.

Building rapport — a sense of connection and trust — is the primary goal of the first session. The therapist does this through:

• Active listening: giving full attention, avoiding interruptions, and showing through body language that they’re engaged

• Empathy: trying to understand the client’s experience from their perspective

• Unconditional positive regard: accepting the client without judgment

• Validation: acknowledging the client’s feelings and experiences as real and understandable

• Appropriate self-disclosure: occasionally sharing relevant professional experiences (but keeping the focus on the client)

Research consistently shows that the quality of the therapeutic relationship is one of the strongest predictors of positive therapy outcomes. A strong therapeutic alliance means the therapist and client are working together collaboratively toward agreed-upon goals.

Collaborative Goal-Setting

Toward the end of the first session, the therapist and client begin discussing goals. What does the client hope to achieve through therapy? What would improvement look like for them? This collaborative goal-setting ensures that therapy is focused and meaningful.

The therapist might ask, “If our work together is successful, what will be different in your life?” or “What would you like to focus on first?”. These goals provide direction and help both therapist and client track progress over time.

Closing the First Session

As the session draws to a close, the therapist typically summarizes what has been discussed. This might include acknowledging the main concerns the client has shared, highlighting any strengths noticed, and outlining the next steps.

The therapist provides encouragement, recognizing the courage it takes to seek help. They discuss the frequency of future sessions and schedule the next appointment. Many therapists also check in about how the client is feeling: “How are you feeling about our meeting today? Do you have any questions or concerns?”.

The goal is for the client to leave the first session feeling heard, hopeful, and clear about what to expect moving forward. While one session cannot solve all problems, a strong first meeting creates the foundation for meaningful therapeutic work to come.

Comprehension Questions

1. According to the text, why do many clients feel anxious before their first therapy session?

2. Why is the first impression so important in therapy?

3. What is a “safe space” and why is it important?

4. What are the main elements that therapists explain during informed consent?

5. What are the limits to confidentiality that therapists must explain?

6. How do therapeutic boundaries help clients?

7. What are the ways to help therapists build rapport with new clients?

8. What is the therapeutic alliance and when is it typically established?

9. Why is collaborative goal-setting important in the first session?

10. What should happen at the end of the first session?

VOCABULARY:

Rapport, Boundaries, and Therapeutic Relationship Terms

A. Find words or phrases in the text that match these definitions:

• Easily hurt physically or emotionally (paragraph 1): _______

• The person receiving therapy (used throughout): _______

• Agreement and permission based on full information

(paragraph 5): _______

• The quality of being open and honest (paragraph 5): _______

• Listening with full attention and engagement

(paragraph 11): _______

• Understanding and sharing another person’s feelings

(paragraph 11): _______

• Acceptance without criticism (paragraph 11): _______

• Working together toward a common goal

(paragraph 13): _______

ㅤ

B. Complete the collocations from the text:

1. therapeutic _______

2. _______ spaces

3. informed _______

4. _______ consent

5. build _______

6. establish _______

7. _______ listening

8. open-_______ question

9. _______ regard

10. collaborative _______-setting

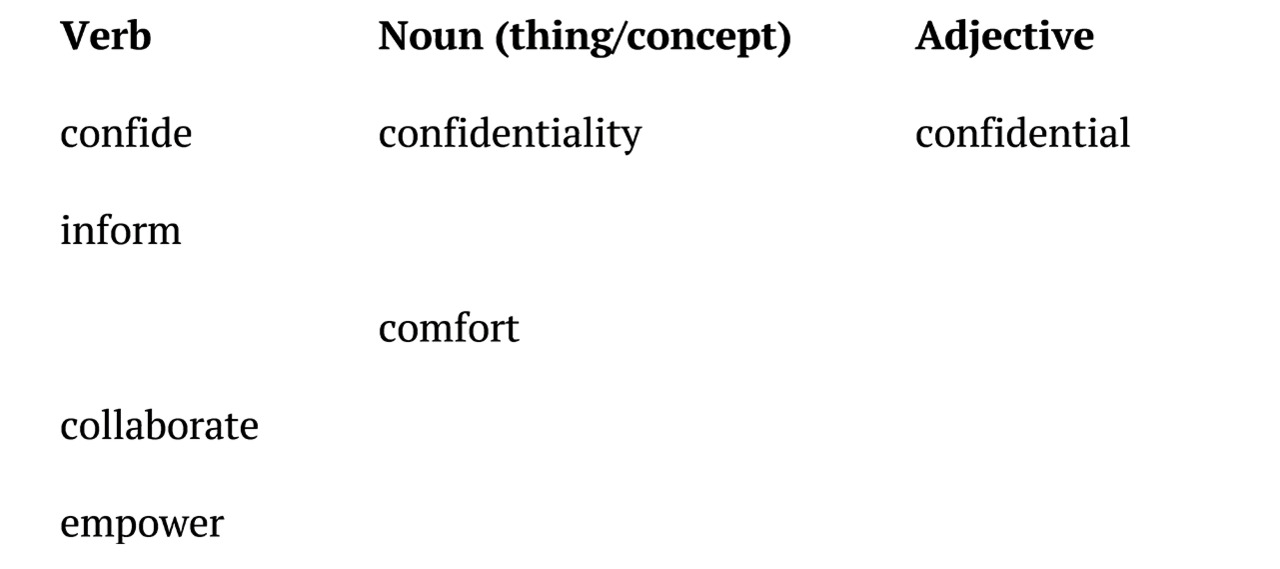

C. Word families

Complete the table:

D. Vocabulary in context

Choose the correct word to complete each sentence:

1. The therapist showed great _______ (empathy / sympathy) by truly understanding the client’s perspective.

2. Clear _______ (borders / boundaries) help create a safe therapeutic environment.

3. The client felt _______ (vulnerable / week) sharing such personal information.

4. Therapists must _______ (establish / install) trust from the very first meeting.

5. The _______ (relationship / rapport) between therapist and client developed quickly.

6. _______ (Informed / Knowledgeable) consent ensures clients understand the therapy process.

7. The therapist practised _______ (active / busy) listening throughout the session.

8. Setting _______ (collaborative / collective) goals helps focus the therapy work.

GRAMMAR FOCUS:

Present Simple vs. Present Continuous / Question Formation

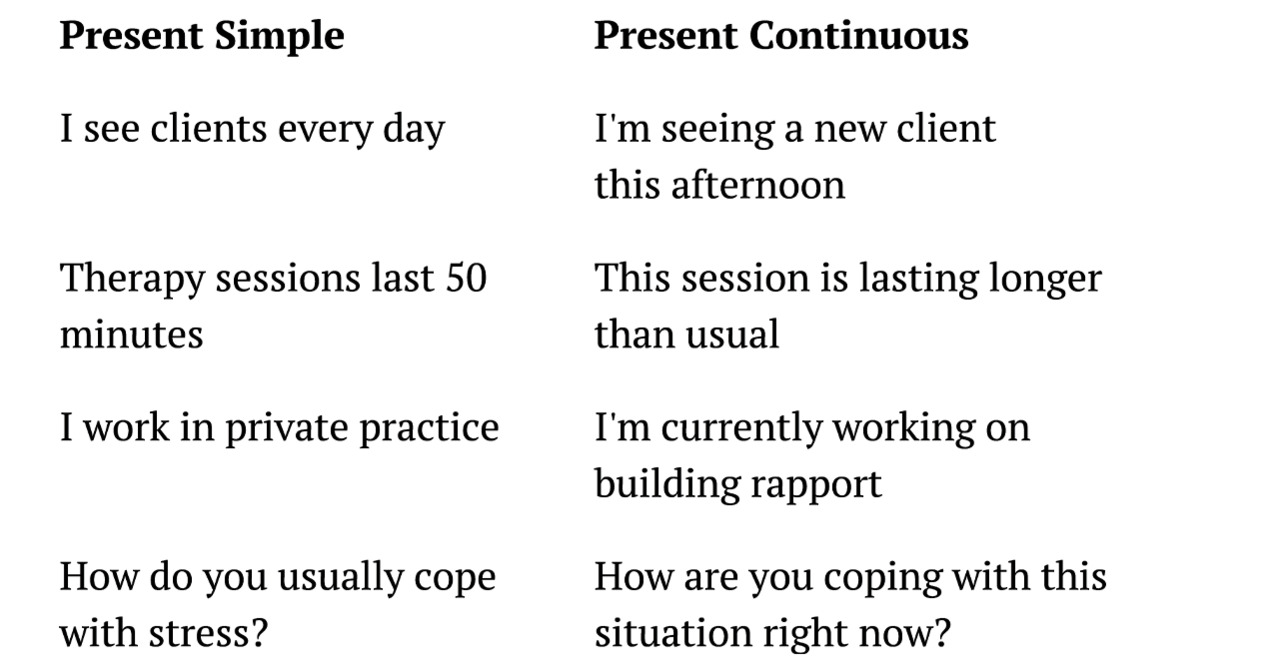

A. Present Simple vs. Present Continuous

We use different tenses to describe different types of actions in therapy:

Present Simple:

• For regular routines, permanent situations, and general truths

• For describing what professionals generally do

Form:

• Affirmative: Subject + verb (+ s/es for he/she/it)

• Negative: Subject + don’t/doesn’t + main verb

• Questions: Do/Does + subject + main verb?

Examples from therapy practice:

• Therapists explain confidentiality in the first session.

• I work with clients on Mondays and Wednesdays.

• Clinical psychologists don’t prescribe medication.

• Do you feel comfortable discussing this topic?

Present Continuous:

• For actions happening now, at this moment

• For temporary situations

• For describing what is currently happening in a session

Form:

• Affirmative: Subject + am/is/are + main verb-ing

• Negative: Subject + am/is/are + not + main verb-ing

• Questions: Am/Is/Are + subject + main verb-ing?

Examples from therapy practice:

• I am listening carefully to what you’re saying right now.

• The client is describing their recent experiences.

• We are working together to identify your goals today.

• Are you feeling anxious at this moment?

Key differences in therapeutic context:

Exercise 1: Choose the correct tense

Complete the sentences with the correct form of the verb in brackets:

1. In our first session, we typically _______ (discuss) what brings you to therapy.

2. Right now, I _______ (explain) how confidentiality works.

3. Most therapy sessions _______ (last) between 45 and 60 minutes.

4. At this moment, the client _______ (share) very personal information.

5. Clinical psychologists _______ (assess) clients using various methods.

6. I _______ (listen) carefully to what you _______ (say).

7. We _______ (not make) major decisions in the first session.

8. _______ you _______ (feel) comfortable talking about this now?

9. Therapists _______ (build) rapport from the very first meeting.

10. I _______ (think) about what goals we should focus on.

Exercise 2: Correct the mistakes

Find and correct the mistakes in these sentences:

1. I’m usually working with adolescents and young adults.

2. Right now, I explain the limits of confidentiality to my client.

3. Are you understanding what I’m saying about boundaries?

4. The therapeutic relationship is building over time.

5. What do you feeling about starting therapy?

6. I’m believing that the first session is very important.

7. We are typically discussing informed consent at the beginning.

8. The client is seeming nervous in every first session.

9. Do you currently experiencing any major stressors?

10. I work on establishing rapport with you at this moment.

ㅤ

B. Question Formation in Therapy

Asking the right questions is essential for building rapport and gathering information. In therapy, we use both closed questions (yes/no answers) and open-ended questions.

Closed Questions (Yes/No):

• Present Simple: Do/Does + subject + main verb?

• Present Continuous: Am/Is/Are + subject + verb-ing?

• Present Perfect: Have/Has + subject + past participle?

Examples:

• Do you feel ready to start therapy?

• Are you experiencing anxiety right now?

• Have you been in therapy before?

Open-ended Questions (encourage detailed responses):

Use question words: What, Where, When, Why, How, Who

Examples:

• What brings you to therapy today?

• How are you feeling about being here?

• What would you like to achieve through therapy?

• How do you usually cope when things are difficult?

• What made you decide to seek help at this time?

Exercise 3: Form questions

Create appropriate questions for a first therapy session using the prompts:

1. (you / ever / see / therapist before)

_______________________________?

2. (what / bring / you / here today)

_______________________________?

3. (how / you / feel / right now)

_______________________________?

4. (you / have / any questions / about confidentiality)

_______________________________?

5. (what / you / hope / achieve / through therapy)

_______________________________?

6. (how long / you / experience / these difficulties)

_______________________________?

7. (you / feel / comfortable / talking about this)

_______________________________?

8. (who / know / that you / come / therapy)

_______________________________?

Exercise 4: Open or Closed?

Identify whether these questions are open or closed. Then, rewrite the closed questions as open questions:

1. Do you have a support system? __________

2. What does your support system look like? __________

3. Are you sleeping well? __________

4. Have you thought about your goals for therapy? __________

5. What brings you here today? __________

6. How are you managing stress? __________

7. Is this situation affecting your relationships? __________

8. Do you want to tell me more about that? __________

COMMUNICATION:

Intake session

Setting: Dr. Maria Santos, a clinical psychologist, is meeting her new client, Robert, for the first time. Robert is a 28-year-old man who has been experiencing anxiety.

Part 1: The Greeting and Opening

Dr. Santos: Hello, Robert? I’m Dr. Santos. It’s nice to meet you.

Robert: Hi. Nice to meet you too.

Dr. Santos: Please, follow me. My office is just down this hallway. (They walk to the office) Have a seat wherever you’re most comfortable.

Robert: Thank you. (Sits down, looks a bit nervous)

Dr. Santos: So, I know first sessions can feel a bit awkward or strange — you’re talking to someone you’ve just met about personal things. That’s completely normal. We’ll take things at your pace today.

Robert: Okay, that’s good to hear. I am feeling a bit nervous, actually.

Dr. Santos: That’s very understandable. Before we get into what brings you here today, I need to go over some important information about how therapy works and confidentiality. It might feel a bit formal at first, but it’s important that you know what to expect. Does that sound okay?

Robert: Yes, sure.

Part 2: Explaining Confidentiality

Dr. Santos: Great. So, first of all, everything we discuss in our sessions together is confidential. That means I don’t share what you tell me with anyone else without your written permission. This confidentiality is really important because I want you to feel safe talking openly about whatever is on your mind.

Robert: Okay, that’s clear to me.

Dr. Santos: However, there are a few limits to confidentiality that I’m legally required to tell you about. If I believe you’re at risk of harming yourself or someone else, or if there’s suspected abuse of a child or vulnerable adult, then I would need to take action to ensure safety. Also, if a court orders me to release records, I will have to comply. But in all of these situations, I would discuss it with you first whenever possible. Do you have any questions about confidentiality?

Robert: No, I think I understand. Those exceptions make sense.

Dr. Santos: Good. And just so you know, you can ask questions at any time — either today or in future sessions. This is your time, and I want you to feel comfortable.

Part 3: Discussing the Therapy Process

Dr. Santos: So, let me tell you a bit about how we typically work. Sessions last 50 minutes, and most people find that meeting weekly works well, at least initially. We’ll work together to identify your goals and figure out the best approach to help you. My style is collaborative — that means we’re working as a team. You’re the expert on your own life, and I’m here to provide support, tools, and a different perspective.

Robert: That sounds good. I was worried you might just tell me what to do.

Dr. Santos: (Smiles) No, therapy is really a collaborative process. I’ll offer suggestions and we’ll explore different strategies, but ultimately, you’re making the decisions about your life. My role is to support you, ask questions that might help you see things differently, and provide evidence-based techniques that might be helpful.

Robert: Okay, I like that approach.

Dr. Santos: I’m glad. Now, I do want to mention that therapy can sometimes be uncomfortable. When we talk about difficult experiences or emotions, it can bring up challenging feelings. That’s actually a normal part of the process, and it often means we’re working on something important. But I’ll always check in with you about how you’re doing, and we can adjust our pace as needed.

Part 4: Exploring the Client’s Concerns

Dr. Santos: So, Robert, tell me — what brings you to therapy?

Robert: Well, I’ve been struggling with anxiety for a while now, maybe about six months. It’s been getting worse recently, and it’s starting to affect my work.

Dr. Santos: I appreciate you sharing that. When you say “anxiety”, what does that look like for you? What are you experiencing?

Robert: It’s mostly worry. I worry about everything — work performance, what people think of me, whether I’m making mistakes. And physically, I feel tense a lot. My heart races sometimes, especially at meetings.

Dr. Santos: That sounds really challenging. It takes a lot of energy to carry that constant worry around. You mentioned it’s affecting your work. Can you tell me more about that?

Robert: Yeah, I’m having trouble concentrating. I keep second-guessing my decisions. I even avoided a presentation last week because I was so anxious about it.

Dr. Santos: I hear you. It sounds like the anxiety is limiting what you feel able to do. That must be frustrating.

Robert: It really is. I used to be more confident.

Part 5: Beginning Goal-Setting

Dr. Santos: Robert, if our work together is successful, what would be different for you? What change would you like to see?

Robert: I’d like to feel calmer, more in control. And I want to be able to do my job without this constant worry hanging over me.

Dr. Santos: Those are great goals. Feeling calmer, having more control, and being able to engage fully with your work. We can definitely work on those things together. In our future sessions, we’ll explore where this anxiety comes from and develop practical strategies to help you manage it.

Robert: That would be really helpful.

Dr. Santos: (Glancing at clock) We’re coming toward the end of our time today. Before we finish, I want to check in — how are you feeling about our conversation today?

Robert: I feel good, actually. I was nervous coming in, but I feel like you understand what I’m going through.

Dr. Santos: I’m so glad to hear that. It takes courage to take this step and come to therapy, and I want you to know that I’m committed to supporting you through this process. Let’s schedule our next session for the same time next week. Does that work for you?

Robert: Yes, that works.

Dr. Santos: Perfect. And Robert, if anything urgent comes up between now and then, you can call the office. But otherwise, I’ll see you next week. Take care.

Robert: Thank you, Dr. Santos. See you next week.

TASK 1: Comprehension and Analysis

Answer these questions about the dialogue:

1. How does Dr. Santos make Robert feel comfortable at the beginning?

2. What does Dr. Santos explain about confidentiality?

3. What are the limits to confidentiality that she mentions?

4. How does Dr. Santos describe the therapy process?

5. What type of questions does Dr. Santos use to explore Robert’s concerns?

6. What are Robert’s main goals for therapy?

7. How does Dr. Santos show empathy during the conversation?

8. What does Dr. Santos do at the end of the session?

TASK 2: Identifying Communication Techniques

Find examples in the dialogue where Dr. Santos uses these rapport-building techniques:

1. Normalizing the client’s experience: _______

2. Asking open-ended questions: _______

3. Reflecting/validating feelings: _______

4. Explaining the collaborative nature of therapy: _______

5. Checking in on the client’s comfort: _______

6. Summarizing what the client said: _______

7. Acknowledging the client’s courage: _______

TASK 3: Role Play Practice

Work in pairs. Student A is the therapist, Student B is the client.

Scenario 1: A new client’s first session. The client is feeling depressed and withdrawn. Practice:

• Greeting and creating comfort

• Explaining confidentiality

• Using open-ended questions

• Building rapport

Scenario 2: A client who is anxious about confidentiality. Practice:

• Addressing their concerns

• Explaining limits clearly

• Checking for understanding

Scenario 3: A first session with a client who has been in therapy before (but with a different therapist). Practice:

• Asking about previous experience

• Discussing expectations

• Collaborative goal-setting

ㅤ

TASK 4: Discussion Questions

Discuss with a partner or in small groups:

1. Why do you think the therapeutic alliance is so important?

2. What might happen if a therapist doesn’t explain confidentiality clearly?

3. How can a therapist balance being warm and friendly while maintaining professional boundaries?

4. What cultural differences might affect how rapport is built in the first session?

5. Why is it important to give clients choice and control from the first meeting?

6. How would you feel as a client in your first therapy session?

PROFESSIONAL PRACTICE:

Introducing the Therapeutic Framework and Informed Consent

Understanding how to explain the therapeutic framework and obtain informed consent is a critical professional skill for all mental health practitioners.

Key Components to Cover in a First Session

1. Welcome and Orientation

Create a warm, welcoming environment from the moment of first contact. Your goal is to help the client feel safe and comfortable enough to share personal information.

Sample language:

• “Welcome. I’m glad you’re here. Please, have a seat wherever you feel comfortable”.

• “I know it can feel a bit uncomfortable talking to someone new about personal matters. That’s completely normal, and we’ll take things at your pace”.

• “Before we begin, do you have any immediate questions or concerns?”

2. Explaining Confidentiality

Sample language:

• “Everything we discuss in our sessions is confidential. This means I don’t share what you tell me with anyone without your written permission”.

• “Confidentiality is essential because I want you to feel safe talking openly about whatever is on your mind”.

• “However, there are some important limits I need to tell you about…”

Explaining the limits:

• “If I believe you are at serious risk of harming yourself, I will need to take steps to ensure your safety”.

• “If I believe you are at risk of harming someone else, I have a duty to warn”.

• “If I suspect abuse or neglect of a child, elderly person, or dependent adult, I’m legally required to report it”.

• “If a court orders me to release records through a subpoena, I will have to comply”.

• “In all of these situations, I would discuss it with you whenever possible”.

Always ask: “Do you have any questions about confidentiality?”

3. Explaining the Therapy Process

Sample language:

• “Our sessions will last 50 minutes, and most people find weekly sessions work well at first”.

• “Therapy is a collaborative process. We’ll work together to identify your goals and figure out the best approach”.

• “My role is to listen, ask questions, offer different perspectives, and teach you tools and strategies that might help”.

• “Your role is to be as open and honest as you feel comfortable being, and to let me know if something isn’t working for you”.

• “I should mention that therapy can sometimes be uncomfortable. When we discuss difficult experiences or emotions, it can bring up challenging feelings. This is often a normal part of the process”.

4. Discussing Boundaries

Sample language:

• “Our sessions will take place here at this office, at the same time each week if that works for you”.

• “If you need to contact me between sessions, you can call the office and leave a message. I typically return calls within 24 hours”.

• “For emergencies, I’ll give you information about who to contact”.

• “Our relationship is a professional one, which means we won’t have contact outside of these sessions beyond what’s necessary for your treatment”.

5. Collaborative Goal-Setting

Sample language:

• “What would you like to achieve through our work together?

• “If therapy is successful, what will be different in your life?”

• “What would you like to focus on first?”

• “These goals will help guide our work and help us track your progress”.

6. Checking for Understanding and Comfort

Throughout the session:

• “Does that make sense?”

• “Do you have any questions about what I’ve explained?”

• “How are you feeling about what we’ve discussed so far?”

• “Is there anything you’d like me to clarify?”

7. Closing the Session

Sample language:

• “We’re coming to the end of our time today. Let me summarize what we’ve discussed…”

• “I want to acknowledge that it takes courage to come to therapy, and I appreciate you sharing with me today”.

• “How are you feeling about our conversation today?”

• “Let’s schedule our next session. Does the same time next week work for you?”

• “If anything urgent comes up before then, please call the office”.

Practice Exercises

ㅤ

Exercise 1: Explaining Confidentiality

Write a short explanation of confidentiality and its limits that you would give to a new client. Include:

• The general principle of confidentiality

• Why it’s important

• The specific limits

• An invitation for questions

Exercise 2: Responding to Client Questions

How would you respond to these client questions?

1. “Will you tell my family what we talk about?”

2. “What happens if I tell you I’m thinking about hurting myself?”

3. “Can we be friends on social media?”

4. “Can I text you between sessions?”

5. “How long will I need to be in therapy?”

6. “What if therapy doesn’t help?”

ㅤ

Exercise 3: Building Your Own Script

Create your own introduction for the first session. Include:

• Greeting and creating comfort

• Brief overview of what will happen in the session

• Explanation of confidentiality

• Description of the therapy process

• Invitation to share what brings them to therapy

Practice your script with a partner, then get feedback.

Exercise 4: Role Play

In pairs, practice a first session. One person is the therapist, one is the client.

Therapist tasks:

• Create a welcoming environment

• Explain informed consent and confidentiality

• Use open-ended questions

• Practise active listening

• Build rapport

• Collaboratively set initial goals

• Close the session appropriately

Client tasks:

• Be yourself, or role-play a specific scenario

• Ask questions about confidentiality or the process

• Share a concern (real or imagined)

• Give feedback to the therapist afterward

After 15–20 minutes, switch roles.

Vocabulary and Collocations for Unit 2

rapport — раппорт, контакт

therapeutic alliance — терапевтический альянс

confidentiality — конфиденциальность

boundaries — границы

informed consent — информированное согласие

safe space — безопасное пространство

initial therapy session — первая терапевтическая сессия

professional encounter — профессиональная встреча

make an appointment — записаться на прием

feeling anxious — чувствующий тревогу/испытывающий чувство тревоги

uncertain — неуверенный

vulnerable — уязвимый

foundation of trust — основа доверия

collaborative relationship — совместные отношения

first impression — первое впечатление

make eye contact — устанавливать зрительный контакт

warm greeting — теплое приветствие

speak freely — говорить свободно

opening conversation — вступительная беседа

at your pace — в вашем темпе

legal formality — юридическая формальность

ethical cornerstone — краеугольный камень этики

empower clients — наделять клиентов полномочиями

establish transparency — установить прозрачность

private information — частная информация

risk of harming — риск причинения вреда

suspected abuse — подозреваемое насилие

therapeutic boundaries — терапевтические границы

professional limits — профессиональные ограничения

session structure — структура сессии

contact between sessions — контакт между сессиями

social media policies — правила/политика социальных сетей

physical boundaries — физические границы

role clarity — ясность ролей

build trust — выстраивать доверие

build rapport — выстраивать раппорт

open-ended question — открытый вопрос

active listening — активное слушание

empathy — эмпатия

unconditional positive regard — безусловное позитивное принятие

validation — валидация

appropriate self-disclosure — уместное самораскрытие

therapeutic relationship — терапевтические отношения

positive therapy outcomes — позитивные результаты терапии

collaborative goal-setting — совместная постановка целей

track progress — отслеживать прогресс

client — клиент

collaborative — совместный

establish boundaries — устанавливать границы

verbal consent — устное согласие

confide — доверять

confidential — конфиденциальный

comfortable — удобный, комфортный

collaborate — сотрудничать

collaboration — сотрудничество

empower — наделять полномочиями

empowerment — наделение полномочиями

empowered — наделенный полномочиями

sympathy — сочувствие

borders — границы (географические)

knowledgeable — осведомленный

collective goals — совместные/коллективные/общие цели

UNIT 3.

INITIAL ASSESSMENT

LEAD-IN:

Information Gathering and Sensitive Questioning Skills

Activity 1: Role-play everyday information gathering

Work in pairs. Take turns asking personal questions in these everyday situations:

• Meeting a new neighbour who has just moved in

• Interviewing someone for a shared apartment

• Getting to know a colleague at a new job

Discuss: What questions did you ask? Which questions felt comfortable? Which felt too personal?

Activity 2: What information matters?

Look at the list below. When meeting a client for the first time, which information is most important to gather? Rank these from 1 (most important) to 10 (least important):

• Current problem/reason for seeking help

• Family background

• Medical history

• Work/education history

• Past mental health treatment

• Current medications

• Social support system

• Childhood experiences

• Current living situation

• Hobbies and interests

Compare your rankings with a partner. Explain your choices.

Activity 3: Sensitive vs. direct questioning quiz

Which question is more appropriate for an initial assessment? Discuss why:

1. a) Have you ever tried to kill yourself?

b) Have you ever had thoughts of harming yourself or ending your life?

2. a) Tell me about your drinking habits.

b) Do you drink alcohol?

3. a) Why did you come here today?

b) What brings you here today?

4. a) Are you depressed?

b) How would you describe your mood lately?

5. a) Do you have problems with your family?

b) Tell me about your relationships with family members.

Note: Most questions require question marks. But in clinical practice open-ended alternatives using imperatives like “Tell me about…” or “Describe…” are also acceptable as questions, though they are technically requests rather than questions.

Key vocabulary for this unit:

ㅤ

Match the words with their definitions:

1. Presenting problem

2. Intake interview

3. Chief complaint

4. Psychosocial history

5. Risk assessment

6. Mental status examination

7. Rapport

8. Confidentiality

ㅤ

a) The main issue that brings a client to seek help

b) First session designed to gather comprehensive background information

c) Evaluation of potential danger to self or others

d) Systematic observation of a client’s psychological functioning

e) Information about personal, family, social, and cultural background

f) A trusting, comfortable connection between therapist and client

g) The primary symptom or concern in the client’s own words

h) The principle that client information remains private

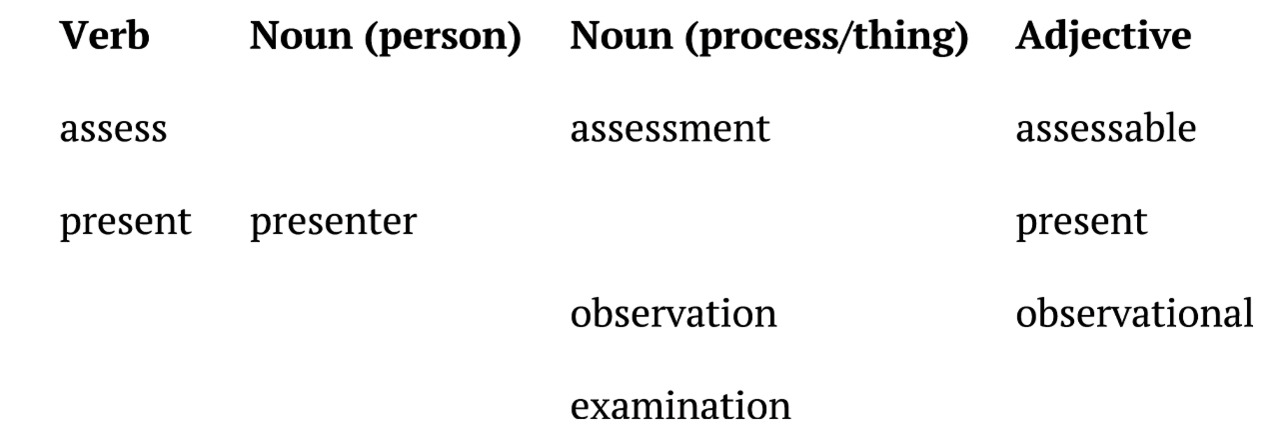

READING:

Understanding the Presenting Problem: Initial Assessment

Pre-reading task