Бесплатный фрагмент - 50 shades of teal management: practical cases

All rights reserved. This e-book is intended solely for private use for personal (noncommercial) purposes. The eBook, its parts, fragments and elements, including text, images and others, may not be copied or used in any way without the permission of the copyright holder. In particular, such use, which would make the eBook, its part, fragment or element available to a limited or indefinite number of persons, including via the Internet, whether access is provided for a fee or free of charge, is prohibited.

Copying, reproduction and other use of an electronic book, its parts, fragments and elements beyond private use for personal (non-commercial) purposes without the consent of the right holder is illegal and entails criminal, administrative and civil liability.

Foreword

Who is this book for?

I’m not a guru, a prophet, a clairvoyant or a scientist. I’m a practitioner who has been following the path of teal management in a single specific company, VkusVill. I don’t have a goal of selling this approach to anyone, since I devote 100% of my time to our organization. But every day, I answer questions related to this new approach — both to myself and everyone else who asks me about it — and I’ve noticed that my answers seem to change sometime in the feelings and actions of those around me. That’s why I took it upon myself to write this book. Of course, I must admit that I hope you read this book to the end, and that it turns out to be useful for you! And if not? Oh well. Send it back to me: Valery Yuryevich Razgulyaev, ulitsa Tayninskaya, 12, apartment 93, Moscow, Russia, 129345. Make sure to leave your phone number or email address, and please tell me how much money you spent on it and the best way to return it to you.

In order to minimize the number of returns, I want to warn you right away: this book is by no means about "teal" organizations. I believe that "teal organizations," just like "teal people," can’t exist even in theory: these are just stupid labels that somebody pins on companies or their employees. Teal management tools are a different matter entirely: they have already been developed and can be applied in practice in any organization. My book’s goal is to answer key questions regarding teal management: "Why is it necessary?" "What is it?" "How can we transition to it?" "Why is it worth it?" It’s structured around answers to all of these.

In the first chapter, "Why bother?" I describe the problems of traditional management systems, all of which gave rise to the need to invent something new. These are the exact factors that led to the appearance of teal management and continue to inspire more and more new followers to study it.

In the second chapter, "What?" we will examine the main tools of teal management and break down their advantages. The situation is complicated by the fact that many definitions in this sphere have yet to become established. After all, it’s generally accepted to first agree on terminology, and only then begin discussing problems. But since a book does not presume the possibility for such a dialogue, I am forced to offer my own combinations of terms, which I will start to use in the hopes that you will accept them for at least as long as you read this book and we can exist in a single conceptual field. In order to make it easier for you to refer to them, I italicized all of the definitions in the text, and at the end of the book, I’ve included a glossary.

The third chapter, "How?" suggests approaches and mechanisms for transitioning to teal management that have proved themselves in practice to interested managers. To be fair, there’s no single algorithm for such a transition, but I will suggest several different options that each reader can use creatively in their own specific use cases — after all, every individual case is always unique.

In the fourth chapter, "Why?" I tried to put together a theoretical foundation for the problem, gathering scientific studies and explaining particular effects that make teal management not just possible, but as successful and even necessary in the modern world as it has become. This part might not seem to add anything from a practical perspective, but I’m sure that for some people, reading it will serve as an additional reason to get up and start the necessary transformations in their companies without delay, while allowing others to understand more deeply — and, therefore, use more effectively — what I describe in the first three chapters.

Throughout the entire book, I’ll be giving you tasks: they will always be in a separate frame, with the task number indicated. I know I can’t make you do anything, but I sincerely advise that you honestly complete all of them. This will give me more chances to get through to you with my message. If for any reason at all you have any questions, I’ll be happy to answer: send them to my email, razgv@mail.ru.

There’s one more important element. I write about things that differ sharply from your current management practice. For that matter, I’m sure that your practices are successful! That’s why your mind will, more likely than not, desperately resist any attempts to interpret what’s written here. What’s more, the more useful that a given bit of text would be for you, the greater inner resistance you will experience. Your consciousness will start helpfully explaining why everything written in this book isn’t even worth reading further. I beg you: as soon as you feel something like this, stop and try to figure out what’s making you freak out. In order to do this, you have to imagine what would personally happen to you if what you had just read were to turn out to be true. That way, you can understand something important about yourself. Only after you change can you achieve any of the other results of your work.

Finally, I’m not pushing for anyone to move toward teal management. Moreover, this book won’t even come close to working for everybody who thought they’d be interested in it! You can understand whether it will work for you by working through the following color system of management styles.

Color scheme of management styles

There are various approaches to management. They can be conveniently divided into eight main types which completely describe all possible variations and are differentiated by the following colors.

Blue

A group of top-notch experts (we’ll call them experts) who are forced to work together because they sequentially participate in the process of creating value for the client, all while constantly arguing (openly or not) whose functions are more important. Everyone sticks to their narrowly specialized field and takes responsibility for what they know best, but they insistently do not want to leave that comfort zone; therefore, shared tasks are accomplished only with difficulty. This system of management works excellently for associations of experts in various industries.

Green

A family where people are the most important element. Many of them are forgiven their imperfections. A family business where everyone is appreciated for their personal qualities: this means that relationships between employees are good, but results sometimes fail to measure up — since everyone is responsible for everything, nobody is specifically responsible for anything. For companies based in the family model (just like an actual family — they need to be managed, too), this system is irreplaceable.

Red

One person single-handedly manages everybody else — and they, figuratively speaking, are that person’s legs, arms, eyes… Even when a hierarchy technically exists among their subordinates, this person gives everybody orders and personally demands results from them. The "monarch" takes full responsibility for what takes place in their "kingdom" and directly controls all of their "subjects," criticizing their loyalty and becoming a bottleneck for everything. However, this system can be useful for doing dirty work that demands the joint efforts of a group of people.

Yellow

A classic bureaucracy, with all the respective pluses and minuses of predictability for every employee. Everything by the rules, plain and clear, and everyone takes responsibility for whatever processes take place within their respective job descriptions. Unfortunately, this leads to formalism ("when you do your job, fill out the paperwork; when you don’t, fill out more"), but this can be useful in situations where limited resources need to be distributed, and fairness must take precedence.

Purple

A classic corporation where internal wars are constantly being fought, seemingly for the benefit of the corporation itself; however, the losses are also considerable. A constant race for perfection, cutthroat competition and the embodiment of the inhumane principle of "the end justifies the means" — when anything goes, so long as you get results.

Teal

A complete rejection of managers. In the best-case scenario, they can fulfill the roles of assistants: without forcing anything on anyone, they limit themselves to merely training self-management skills in their team. Here, everyone takes responsibility for the fulfillment of those promises that they take on for themselves, which ideally suits companies in constantly changing situations that demand a flexible approach. (The teal management strategy will be described in more detail in the second chapter.)

White

The ideal management system of the future, where subordinates voluntarily obey managers that they personally choose in the name of unlocking as much of their potential as possible, when everyone takes responsibility for the decisions that they make within the framework of such obedience. This contains all of the advantages of the other forms of management, without any of their downsides. Unfortunately, at the current stage of our social development, this is an unachievable dream — we can only strive towards this model for now.

These colors aren’t usually found in their pure form. What’s more, in any company, they are all always present — the only question is which of them takes priority. If it’s still hard for you to figure out which of the colors is dominant in your organization after taking into account the above information, then you can take a test online at http://biryuzovie.ru. The only thing is that practice has shown that in order to get the right answer, you have to answer honestly, without passing off what you want as what you have.

Is this book right for you?

Based on the aforementioned color scheme, it stands to reason that companies that want to transition to teal management might currently use blue, green, red, yellow or purple management styles. Currently, the most widespread styles are purple corporations, yellow bureaucracies and green family businesses. For them, there are already well-trodden paths that allow them to make a successful transition to teal management. In fact, the second chapter of this book will focus specifically on managers in organizations that primarily use purple corporate management. Of course, others are by no means forbidden from reading; what’s more, it might even turn out to be useful for them. But in order to realize the practical side of the matter, I advise using different approaches, which I’ll outline for each of the colors below.

Holacracy is an approach to organizing a company based on organizing holons, a kind of circle for solving every kind of recurring task: within these circles, there are roles which various employees can fulfill, who receive these roles fully and independently make decisions within them.

For a yellow bureaucracy, a formalistic method works best, and the holacracy is the clearest example of such an approach. This is an approach to organizing a company based on organizing holons, a kind of circle for solving every kind of recurring task: within these circles, there are roles which various employees can fulfill, who receive these roles fully and independently make decisions within them. Brian Robertson’s book (1) outlines all the protocols for meetings to move a company into teal management. There is also a "lighter" version, sociocracy, which welcomes the consolidation or alteration of work protocols by employees themselves, through a single required element of every meeting: a reflection on any process and its final results.

Sociocracy — a “lighter” version of holacracy, which welcomes the consolidation or alteration of work protocols by employees themselves, through a single required element of every meeting: reflection on any process and its final results.

A green family business is best helped by a psychological method, in which professional psychologists work with the team, both as a whole and with each individual member, over the course of two or three years. The goal is to achieve such integrity in each unit of the company as to make any other management style (save for teal management) can hardly be possible. For that matter, all of the employees voluntarily take on additional responsibilities connected with this management style — or voluntarily leave, having understood that they are driven by something else and they don’t want to continue doing their current job if they can’t find another suitable task within the organization. Of course, it’s far faster to simply divide everyone into those who are simply out of their league and those who pull double the weight, but companies aren’t organized in this way by accident. For that reason, these post-flight analyses will depend on the people who are willing to take part in them and support them — with specific examples from specific employees rather than generalizations.

For blue and red organizations, there are no established successful paths of transitioning to teal management, since such a transition happens extremely rarely. But based on the logic of the color scheme, we can suggest the following.

• Blue: it might seem that in order to get a teal company, all you need to do is add some green, but it’s not that simple, as each of the experts in such an organization has successfully protected their position many times. As a result, a separation of competencies and spheres has occurred: nobody gets in their neighbor’s way, but simultaneously doesn’t let anyone get close to themselves, either. In order to change the situation for the better, you have to start doubling your responsible parties (there will be more about this technique in the second chapter). Additionally, you need to start finding a common goal and establish shared responsibility for its achievement. This will be constantly disputed, since each person in the company will habitually begin to demonstrate that work is going just fine on their own individual front, but the point of this initiative is to make all of these top-flight specialists, with their widely varying specializations, understand that the most important front is a shared one.

• Red: since everything in such an organization is tied up in its leading figure, that’s the person that you have to work with — specifically, through a professional business trainer and psychologist who will help the boss to gradually understand themselves and restructure the company’s management to allow more delegation of power and less worry over potential theft. You can start by getting acquainted with Dennis Bakke’s “The Decision Maker.” (2) Unfortunately, you can’t get away with just reading a book, since you’ll have to prove to the “monarch” over and over again the advantage that they’ll receive from passing their work off to other people — even if they do it worse — over and over again, using specific examples.

Chapter One. Why bother?

The majority of the definitions will be given in the following chapter, but at the beginning of the book, we still have to agree on what we understand as "management." We often use this word in everyday life, while hardly even thinking about how we might explain the concept clearly.

✎Task 1

In your opinion, what is management? Try to come up with a definition for this concept.

Stop! Don’t skip this first task, or any of the ones that follow it. I’m certain that you don’t like theoretical work all that much, and you might even complain about how much hot air and how little practical material is in most management and leadership books. But here’s the practice you wanted, and it will allow you to make sense of your own management. Please don’t ignore this task; stop and do it honestly, and only then go on reading. Believe me, I’m insisting on this for your own good.

Management — a meaningful action that leads to a necessary and expected result.

So now we come to management. In the general sense of the word, we’re always talking about a certain meaningful action that leads to a necessary and expected result. The simplest example: when we drive a car, obedient to every movement of the steering wheel in our hands and pedals under our feet, nobody has any reason to doubt that we’re not controlling it. That management has certain limitations related to the physical capabilities of the car, which can’t speed up past a certain point or stop instantaneously. But we can clearly distinguish this situation from another, where we might say that driver lost control of the car: when turning the wheel or any manipulations of the pedals don’t have any result, as the car is being carried in a direction where we have no desire to go. I believe that the exact same thing can happen in any other situation: when we get an undesirable result over some length of time and can’t do anything about it, we have to honestly admit to ourselves that we aren’t controlling that situation. There are two options here. Either we’re in a case like with the car, where we have lost control and can first formulate, then organize the necessary conditions for returning that control — or we never actually controlled the situation in the first place, and the fact that it was in some way advantageous in the past is in no way connected to any actions of our own.

I stopped and devoted so much attention to these seemingly obvious things because right now, the majority of readers will face a serious battle with themselves. I’m going to assert things that are so sad, your subconscious will start trying to convince you of practically anything under the sun — anything to avoid believing these realities. Then mechanisms of self-deception, refined by all of your accumulated life experience, will come into play: well, of course you’re right, and not the author at all. What’s more, how could he possibly compare if he’s in a totally different job, or region, with different people, all in a different industry… And who is this author anyways, and why is it worth listening to him?! No matter what regalia and qualifications I might have, they won’t be weighty enough to warrant listening to; my experience won’t be suitable, and my education will seem insufficient. Therefore, I won’t even bother talking about them; instead, reader, I ask the following of you.

Task 2

For some time, turn off your inner critic and remember someone who held a great deal of authority in your eyes, whose words you always listened to, at the very least; imagine that that person is the one telling you all of these things, and then read the text in their voice.

I think you’ll agree that over the entire course of the 20th century, the very best leaders on our planet tried to create a certain kind of autopilot within their individual companies, all in the hopes of achieving the optimal result. But a cursory overview of business statistics would show you that nobody ever found this "sorcerer’s stone": companies both large and small, from around the world continue to run themselves into the ground, which we can hardly call a desirable result of their management strategies. I’ll go on to bring in examples of negative phenomena in your organization: those that you know and don’t like, but can’t influence in any way, shape or form. How do I know about them? They’re everywhere! For me, this means one thing in particular: leaders in companies have lost control, just like in the aforementioned example with the driver and the car. I understand that this is really hard to accept: after all, others judge us by how well we manage, and you probably measure your own success by the very same criteria. We spend lots of time and energy on this, and if we’re not the owners of a company, then we even get paid for this management! But how can we admit here that we don’t do this? Still, I ask you to judge yourself not by the amount of time spent or how tired you are, but by the results of your actions. So let’s look at what we have in the following categories.

Span of control: the average number of subordinates underneath a single manager.

Management expenses

A traditional system of management resembles a pyramid, where the chief executive is at the very top, and rank-and-file workers make up the foundation. Between them lie many layers of sub-managers. Their quantity depends on the size of the organization and its span of control: the average number of subordinates underneath a single manager.

Once you know the number of employees in a company and its span of control, you can always count the number of levels and the number of managers on each of them. For example, with a span of control of 5 and 156 employees, we have:

• 125 rank-and-file employees;

• 25 middle managers;

• 5 upper managers;

• and one chief executive.

What might the expenses of managing such a system be? In order to compare companies amongst themselves, it would be best to use the percentage of total expenditures on managers out of total payroll. For example, if a manager in our example company earn on average twice as much as their subordinates, then:

• 125 rank-and-file employees receive 1 salary each = 125 base salaries;

• 25 middle managers receive 2 base salaries = 50 base salaries;

• 5 upper managers receive 4 base salaries = 20 base salaries;

• 1 chief executive receives 8 base salaries = 8 base salaries.

In total, all of the managers in this company receive a total of 50 +20 +8 = 78 base salaries, which makes up 78 / (78 +125) = 78 / 203 ≈ 38% of the company’s overall payroll — which is a considerable line item of expenses for any company! What’s more, the bigger the organization, the more levels of management and managers, which means a higher percentage that their salaries make up out of the overall payroll, even though they do not create any of the added value for the client. Doesn’t sound too inspiring, does it? But this is the most insignificant problem in a classical system of management.

Constantly overloaded management

In my consulting days, I thought that many managers didn’t want to start the projects that their companies obviously needed due to their insufficient competency and lack of desire to admit as much in order to start studying the topic at hand. The reality turned out to be far more banal: extremely competent, hard-working, knowledgeable and industrious managers are in constant time trouble: they don’t even have enough time to finish with the current routines being imposed upon them, like an avalanche in the mountains. All this happens, I’ll remind you, because of the classical management system, where problems are escalated from the bottom up. As a result, the higher a manager’s level, the more subordinates they have and the more problems end up on their plate.

They physically don’t have time to solve all of them, which leads to overwork during the week, regular work during the weekends and a lack of relaxation, even on vacation. But none of this helps, and tasks start to get stuck on a waiting list, and some of them get lost from sight forever in favor of more urgent and important ones. Meanwhile, the manager understands that the problem they themselves don’t solve might result in serious losses both for the whole company and for themselves personally, leading to a state of constant stress that the manager or boss begins to project outwardly. This is especially true for those employees who inform them about new problems or are in any way, shape or form party to them. As a result, a confrontation between bosses and their subordinates begins, which only worsens the situation, since the manager must now spend their energy on that, too.

Slow problem solving

Meanwhile, the organization’s real problems begin to get solved more and more slowly. After experiencing an inappropriate reaction from their managers, subordinates share information about new problems less and less frequently with the higher-ups, while lacking the necessary privileges and resource to solve them at lower levels. What’s more, due to the fear of having the dogs set on them, information starts to transform in order to protect the person sharing it — or, when such shielding is impossible, it gets completely stuck without ever reaching the boss. Interestingly, decisions traveling in the opposite direction experience their own losses as well. I conducted an analysis which showed that in transitioning from one level of management to another, around 30% of information gets lost. This means that if only 70% of information remains when an order gets to your direct subordinates, then in transmitting this order to the next level of management, you have to take 70% of these 70%: 0.7 × 0.7 = 0.49 = 49%, or less than half! Unfortunately, the information doesn’t merely get lost, but also gets twisted: this means that the remaining 51% is filled with something else, often contradictory to your thoughts, words and desires.

Task 3

Multiply this 0.7 by as many layers of hierarchy there are underneath you, and understand how little of what you say gets through to those who will have to directly carry out your orders, and how much distortion is introduced in the process.

Is it clear now why nothing ever happens the way that you planned it?

Now let’s look at the situation from the client’s side, who has encountered some insignificant, minor problem and lets your subordinate know about it. Your subordinate can’t solve the issue themselves and escalates it higher — what else can they do, when that’s always how they act? But the problem isn’t critical, you have more important and urgent tasks, and as a result, you put it off over and over again until at the end of the day you simply forget about it altogether. Then the exact same client runs into the exact same problem half a year later and understands that nobody even tried to take care of him. They tell the exact same employee, now with some surprise, that the problem could have been solved over all of this time. Your subordinate justifies their behavior, saying that they passed the client’s wishes along to their bosses and assures them that they’ll bring up the issue again. But even if they do exactly that, the result will be the same: you just won’t get around to it. And after some time, the exact same client will run into the aforementioned problem. Now put yourself in that client’s position: it’s not hard to imagine what they think about your company and its attitude toward its customers…

Demotivation of rank-and-file employees

All this time, your subordinates find themselves in a very unpleasant position of being wrongly accused. If they report up, then they can be turned into a sacrificial lamb; if they conceal the information, they can be asked at any moment why such a problem exists, but nobody knows about it. As a result, the poor fellow is in a constant state of stress, and even if their manager still had some power to influence the situation, then the subordinate will only lose motivation, stuck in a position of dependency.

What happens as a result? We hire specialists to work on motivating our personnel and pay them salaries, but in actuality, everything that they concoct doesn’t work for long. There’s some mysterious important reason that demotivates people within the framework of a traditional management system. This reason is learned helplessness. We’ll talk in more detail about this reason in the fourth chapter. Now I’ll just say that the essence of this phenomenon comes down to the following: if we take an employee’s rights away, but nevertheless continue to ask as much of them as before, they will start fearing responsibility of any kind and begin to avoid it by any means necessary. This gives a person who is extremely demotivated and dodges responsibility as best they can, lacking any desire to make decisions. Meanwhile, it’s very important to understand that we are the ones who made them that way. After all, in everyday life outside the workplace, everything in this person’s life is the polar opposite: they take responsibility for where they live and what they eat — and if they have children, they’re responsible for their lives, too! So why in the world do they turn out to be "insufficiently responsible" to be worthy of the permissions necessary to make the simplest decisions for the company?

Mass irresponsibility

What’s going on inside the organization? Both managers and their subordinates are becoming hostages of a system of management under which it’s best not to be responsible for anything at all. This became the reason for an unbelievable dearth of good managers, despite a surfeit of qualified specialists. After all, who would be clamoring to take on additional responsibility for other people, too? In such a situation, those who are solely interested in career growth and power begin to flourish. As a result, the situation gets even more complicated: after all, such people consciously surround themselves with others who can’t compete with them and intentionally inflate their staff numbers to seem like more significant managers.

Meanwhile, other employees initially protest at the sight of such phenomena but then, when they understand that their concerns are not being heard, they also begin to lose responsibility, asking themselves, “What, do we really need this? Why should the buck stop here?” They pass the requirement to figure problems out onto their supervisors, who ultimately have no time to do so, since they’re already so busy in the first place…

“Wars” between divisions

Twilight zone of rights and responsibilities — this is a zone between two or more divisions, where nobody in any division has the necessary rights to solve the problems that inevitably arise — and nobody wants to take on the responsibility for doing so.

In a situation where nobody wants to take responsibility, “wars” unavoidably begin to brew between departments and divisions, which also has a negative influence on the overall results of the company’s work. For that matter, it is the divisions that have to work most closely together in order to achieve their common goals that fight the most often! It’s not hard to guess that the reason also lies in the management system.

Everything usually begins with a problem that arises in the twilight zone of rights and responsibilities of two or more divisions — which is where nobody has the necessary rights to solve the problems that inevitably arise — and nobody wants to take on the responsibility for doing so. Otherwise, it would not have become a problem in the first place; it would simply be another task that each of the divisions successfully solves every day. By the way, the most common situation is when the problem at hand arises due to a lack of communication between these divisions: someone didn’t warn someone else, or else they didn’t hear or understand — or merely understood incorrectly. By itself, this is nothing to worry about. The issue is that when the problem arises, nobody is in any rush to solve it. Everyone thinks to themselves, “That’s not my responsibility. We have enough tasks on our own; we won’t have time to do everything otherwise!”

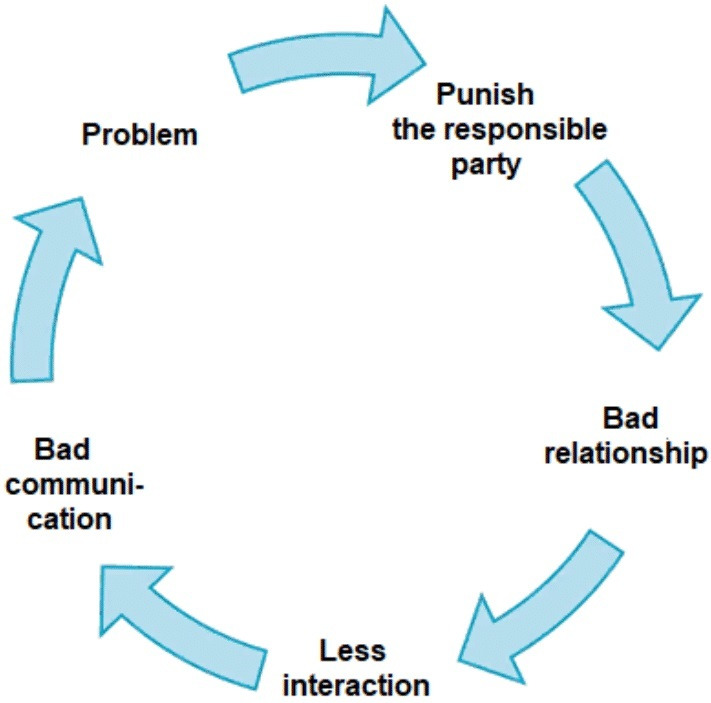

But when nobody solves the problem, it begins to grow, and ultimately ends up becoming so enormous that the big boss at the top of the food chain can see it. Of course, any manager in such a situation has one universal solution: delegate the responsibility to someone. However, regardless of which of these divisions has its representative chosen as the responsible party, they will think that they were unfairly punished in favor of their colleagues from the other department (s). As a result, relationships between employees of these divisions grow worse; they begin to communicate less frequently, and the situation only continues to spin out of control. A vicious cycle is created, which I have drawn out in the diagram below.

Problems begin to appear left and right out of this twilight zone between departments as though from a horn of plenty, even though everything was just fine not long ago. Management gradually begins to distribute responsibility in a decidedly random manner, "rewarding" choice employees without asking whether they have the necessary rights to carry out this responsibility. Alas, some tasks can only be completed in collaboration.

Ultimately, the employees in these warring departments develop prejudices and they begin to assess the situation in a biased manner. It gets to the point that they begin to earnestly believe as though their colleagues really come to work every day and collect a salary in order to set them up and ruin their lives any way they can! This is a fundamentally incorrect conclusion, but it has a deeply destructive effect on any team, and its members can begin to take revenge on their colleagues and actually start making their lives more difficult.

Projects are done slowly and badly

All the principles here have already been explained above. First of all, everyone is always busy. Second of all, a project usually demands the cooperation of several divisions — but how can you make that happen if people don’t want to interact? For that matter, absolutely everyone who wants to push through any changes at all runs into resistance from their colleagues who, first of all, are busy up to their eyeballs, and second of all, who are principally opposed to doing anything together. Besides, it’s often the case that instead of working on the project, all members of the working group spend their time and energy on passing the buck off to one another — a necessary precaution in the event of failure. This leads to projects being done slowly, for a lot of money, and with results that, to put it lightly, are nothing to write home about…

What are you managing, anyway?

If none of the aforementioned points sounds familiar to you, then you can stop reading here: no matter what, you won’t get anything useful out of my book, and will just be wasting your time reading it instead! However, more likely than not, these examples illustrate the state of things (in whole or part) within your company. For that matter, we must note that you know about all of these existing problems and you don’t like them, but you can’t do anything about them. If we return to the analogy of driving a car, then this means that you’ve lost control. At the core of things, you were never in control in the first place; the situation had merely yet to become critical, and you were being carried in the direction where you wanted to go anyway. Now, however, everything has changed, and that means that you need to change, too!

Generally speaking, the "teal" alternative arose specifically to solve these essential problems that accumulated under all previous systems of management and create a new one where such problems cannot exist a priori. We have to note that this has worked in practice, and many managers in many companies have already been able to start using teal tools! That means that if people have the desire, the will, the right creative approach, and the knowledge that you’re about to gain, you’ll be able to do so, too!

But first of all, we have to stop and figure out exactly what it is that you’re managing. One person might say that it’s a company. Another will say that it’s people. A third will say resources. As strange as it is, all of these answers are incorrect. The only thing that anyone actually manages is their influence on other people. Nothing else. Period.

It will probably seem to you that this isn’t much at all, compared to what was listed above. But let’s be realists here. In reality, all we can manage is our influence on the people around us. That has always been the case. Well, if that was enough to let the greatest leaders of the past accomplish those great feats for which we remember them, that means it will be enough for you, especially if you approach the management of your influence on others conscientiously.

For starts, learn to notice the specific kind of influence you have on people and what you get as a result. I have often encountered situations when a manager seems to say, "Full speed ahead!" but it’s nothing but empty words. Instead, all of their actions seem to "pull up the handbrake," so to speak, and then they are surprised that the company is stuck in place and not moving anywhere! It’s worth remembering that this influence comes from every word and behavior, from any gesture or facial expression, and even from silence, inaction or a lack of reaction.

Under no circumstances am I pushing you towards insincerity. That is a worthless endeavor since everyone around you will sense those signals that we cannot consciously manage. I’m asking you to comprehend the results of your influence on your subordinates, to take responsibility for it, and to search inside yourself for those deeper reasons that force us to behave in a certain way. Finally, I am asking you to change your interpretation of the situation. As a result, you will transform your own actions, and thanks to that, new results will follow.

Chapter Two.

What?

The spread of teal tools has already become a trend in transforming management systems, but to this day there remains much confusion about the most elementary questions — both for those who have only just encountered the basic terms and for those who have already studied them in some depth. Around some of these terms, heated arguments have even begun. To be fair, it’s worth noting that it’s primarily theorists who butt heads on such matters. Practitioners simply start realizing the necessary changes in their companies, either overall or within individual departments, insofar as they understand those changes themselves. As luck would have it, they often achieve excellent results, even though they might not have understood everything perfectly to begin with. However, forward movement straightens out these misunderstandings and results in the necessary course corrections on the whole. By the way, some people value teal management for these qualities in particular: its flexibility, speed and efficiency which, aside from all of its other qualities, allow it to easily prevail in a competitive fight with antiquated management systems.

“Teal”

Theoretical arguments begin at the most elemental level, around the name itself: the term “teal.” The thing is that in his book “Reinventing Organizations”, 3 Frederic Laloux based his color scheme on the one in Don Beck’s “Spiral Dynamics”. 4 However, he changed the colors around a little in order to make the development dynamics of a company’s organizational system from one level of his theory to the next fit into the spectrum of visible light: from infrared, which corresponds to the most primitive forms of organization for him, to ultraviolet, which he incidentally doesn’t even mention in his work. The thing is that he stops at teal, which he discovered in the course of his studies in the most contemporary forms of companies at the time. For that matter, classical spiral dynamics has a “teal” of its own, not described in “Reinventing Organizations”. Frederic Laloux’s teal corresponds to “yellow” in spiral dynamics, while “amber” (a shade of yellow) fits in with Don Beck’s deep blue. Besides this, there are other color schemes of management systems as well: in the fourth chapter, you will find a comparison table that I put together specifically to help my readers. To put it simply, before you call out a color, you have to clearly define which color scheme you’re talking about.

In reality, this doesn’t have any influence whatsoever, but such arguments only serve to confuse the situation further. In order to slice through this Gordian knot, we will note that all such discussions boil down to the definition of terms that will be used in our further discussions. That means that proof of the correctness of one version or another doesn’t exist, and cannot exist in principle. In any branch of science, there exists a moment when specialists stop arguing and start negotiating as to what they will begin to call by a particular name or other, because without such an agreement, any further debates are essentially impossible. We have to note that many arguments simply would never have happened if the arguing parties had simply started by defining those words that they planned on using over the course of the argument. That’s why I propose agreeing on the use of "teal" within the framework of this book in terms of management styles as it is understood in "Reinventing Organizations." After all, it is Frederic Laloux to whom we owe the popularization of this term. The aforementioned "Spiral Dynamics" even though it was published significantly earlier, is far less well-known, and often our fellow countrymen find out about it only after getting acquainted with "Reinventing Organizations" and in an attempt to read something further on the subject.

As far as specialized literature that describes the practices of transitioning to the teal system of management is concerned, I recommend that you get acquainted with the bibliography at the end of this book — or visit http://biryuzovie.ru/category/poleznye-knigi/. There you can find a specially assembled list of publications, along with my comments, which I’m constantly augmenting and updating.

There’s one other important aspect. I already spoke about this in the foreword, but I will emphasize it one more time: "teal" organizations and managers don’t exist in nature, and currently cannot even exist theoretically. At the moment, the only thing that can be teal is management within an organization, and I must admit that I have yet to find a single one where it completely corresponds to its definition. The image of the companies illustrated in Frederic Laloux’s book is so tempting that it would seem that real "teal" companies are lurking behind every corner! Alas, that is not the case. I know what I’m talking about, because I have personally been in contact with the founders and employees of six of the firms mentioned by the author, and have also read books written by the aforementioned managers. Their organizations are not "teal," although many teal management tools described by Laloux are used there.

That seems clear enough; these are the pioneers, after all. Who would call the very first capitalists who challenged the reign of bureaucracies "corporations," either? Was it even possible to predict the future of all-powerful bureaucracies in the very first vicars of ancient monarchs, who had previously always collected taxes and held court over all the territory he ruled in person? Any new form of leadership sharply differs from that which preceded it at first glance, but of course, it doesn’t show its full and unvarnished essence right away. Just imagine what teal management would look like in organizations when it begins to saturate all of human culture, rather than being a strange exception from the general rule as it is now — whether for owners, managers and employees or for suppliers, public institutions and clients.

That’s why the most important task today is to find the tools of teal management, employing them in practice and popularizing successful experiences around the world, rather than bragging that you’re already "teal" and your neighbor isn’t. For now, we’re all very far from perfection! To make it easier to understand, I’ll take a more familiar analogy. What would you think about a person who told you that a particular firm is automated, and another one isn’t? Personally I’d decide that they aren’t using the term at hand very correctly: after all, you can only automate a process, not a whole firm. What’s more, the automation of a process has specific goals and clear resources that can be compared with other cases. You can wrack your brains applying the logic to a firm ad infinitum, constantly applying new materials and tools to the process.

And what would you say in response to the assertion that one company is more "automated" than another? How can you even comprehend this if in the first case, all orders are automatically for suppliers while accounting for numerous factors, but in the second case, everything is done in Excel, with no guarantee that all the data from the accounting system makes it into the spreadsheet, and some things entered completely manually? On the other hand, what if in the second case, all cost accounting with suppliers is done using an electronic workflow, while in the first case, people still run around with stacks of papers and spending a month on accounting records at the beginning of every quarter? Based on this analogy, you might get the sense that an organization’s color categorization will always be mixed somehow, but on the other hand, you can try to speak about the color of specific divisions and departments inside of it. No, you can’t do that, either! In different situations, a single manager might behave in completely different ways! Yes, some methods may be more or less characteristic for them, but I am principally opposed to calling a person "red," "teal" or anything in between, even in extreme situations.

Teal leadership — such leadership as increases or at least supports the independence and integrity of an organization’s employees in order to achieve its evolutionary goals.

There are many tools of teal management, and the consistent use of the majority of them for an increasingly wide spectrum of situations is the very path that any organization or manager can use to make significant changes for the better. The most important thing is not to rest on your laurels, always trying to solve problems in new and different ways. Soon, others will start to call such a company "teal," even though this would be a terminological error. After all, there is always an opportunity to do something else in this direction, and it’s far better for a company to focus on specific actions, rather than waving its teal flag in the air.

But we still haven’t answered the question of what this mystical teal management is. According to Frederic Laloux, it is such leadership as increases or at least supports the independence and integrity of an organization’s employees in order to achieve its evolutionary goals. Let’s sort out each of the three "whales" of teal management: evolutionary goal, integrity and independence. Incidentally, it’s interesting that all of these components depend very closely on one another: you can feel this immediately as soon as you try to incorporate any of them in practice, whether at the company level or in just one of its departments.

Evolutionary goal

A company’s evolutionary goal is a result toward which a company strives, having chosen it as the main focus for all of its actions. A company’s evolutionary goal can be easily confused with its mission, which is no surprise: they often sound very similar to one another. But this is only on the surface: in fact, there is indeed a difference between them, and a very significant one at that. Let’s sort out the definitions. A mission expresses what the company does, while the evolutionary goal expresses what should happen as a result of the company’s work. If the mission is inseparable from the organization, then the evolutionary goal demands a description of a result without any ties to a specific organization. For example, a doctor’s mission is to heal people, while their evolutionary goal is for all people to be healthy. In the case of the mission, all other doctors keep one specific doctor from healing patients by performing the same process themselves. However, when taken together, the entire medical community can only help achieve the evolutionary goal. An even larger difference can be seen in the decision-making process in those cases when the mission or evolutionary goal becomes incompatible with the process of making money. An honest company will then rewrite their mission so that it applies to a new type of money earning, while a dishonest company will simply go on making money however necessary without changing its mission. A company with an evolutionary goal, on the other hand, does not do anything that does not directly contribute to its fulfillment in principle, even if it can make them money. The thing is that an organization defines its mission based on its individual needs, while a company is created in order to achieve an evolutionary goal. This means that an evolutionary goal is greater than the company’s own good, and a company will stop at nothing in order to achieve it, even if in the process, it must cardinally change or even stop functioning completely. For this exact reason, competition doesn’t exist for a company with an evolutionary goal — they can only help a company achieve that goal. They’re not competitors, but colleagues instead

Upon hearing such a claim, some people will start to protest: they’ll say that these are just marketing tricks and that people only really live and work for the sake of money while hiding behind pretty metaphors. But if we take any relatively grown-up person who understands that they will unavoidably die in a few dozen years, no matter what they do, and who realized that they wouldn’t take any money with them, then we will see that their actions take on a new meaning. Is it worth placing material values above all else and participating in constant competition with others to make more money? Even if you take “first place” in such a competition, your achievement will quickly fade into oblivion. Isn’t it time to stop and think about more timeless goals? It follows, of course, that it’s very scary to accept the fact that you’ve been running yourself into the ground and all for nothing, as it turns out. But the sooner you ask yourself these unpleasant questions and honestly answer them, the less time you will spend on this unproductive rat race. There is an old Chinese saying: “The best time to plant a tree was twenty years ago. The next best time is today.”

I’ll say it one more time since it’s very important. An evolutionary goal is not merely a pretty candy wrapper that attracts attention to a company. Nor is it a mysterious beast that will inspire employees to give more of their inner resources, or even work for free. It’s not even a motivator. An evolutionary goal is a flag that somebody raises high in the air and gathers those who share its values. Might that group of people include those opportunists who are simply playing along? Yes, without a doubt. But the purpose of an evolutionary goal is not to dispose of these people, but to surround them with people who actually share these values while providing a clear touchstone for everyone to use in solving all manner of conflicts since they can always be seen in the context of achieving a shared evolutionary goal.

Evolutionary goal — a result towards which a company strives, having chosen it as the main focus of all of its actions.

In setting your organization’s evolutionary goal, I strongly advise that you use the following principles:

1. Always describe the result you want, not the process of achieving it

2. Describe it as something that has already been achieved — in other words, how things will look when you have already achieved success

3. This result should be beneficial for those around you

4. It should be distinct from the company, which means that it should exist separately

5. You should not have achieved this result already — otherwise, why would you be striving towards it?

6. It should appear in the world thanks to you, but other people can create it as well

7. The goal should be specific, and what your company does should be clear to anyone based on its definition alone. "For all good and against all bad" cannot be an evolutionary goal; you should specify what you want to change in order to make that a reality

Seem too difficult? Don’t worry, it’s worth it! And you will only benefit from the fact that it’s not just a marketing ploy! An honest evolutionary goal that does something useful for the world around you: what else could do a better job of drawing attention to the company? For that matter, you get the bonus of free material for word-of-mouth advertising: all as a result of the fact that everything real and honest catches people’s attention, as a result of the excess of empty marketing-driven tricks in the world, and inspires them want to give up their money, attention and energy. A good evolutionary goal meets all the necessary specifications of viral messaging from Jonah Berger’s “Contagious: Why Things Catch On"5—although, of course, this isn’t the be-all and end-all of the company.

Integrity

Integrity — a state in which a person makes the best decisions they can possibly make.

Let’s move on to the next term. Integrity is a state in which a person makes the best decisions they can make. You are not in a state of inner conflict, which can easily be determined by the strong negative emotions that you feel. In application to teal management, integrity means that each employee is needed in their entirety by the company, along with their emotions, because it is these emotions that give those employees the energy to take action, making work truly interesting for everyone around. In order to say that a person has integrity, they must also be completely honest, and not only with the others, but that even most important with themselves: this is just the bare minimum, and it must be accompanied by sincerity and openness.

Some people are afraid of honesty, as it might interrupt their present "success" or even destroy the entire organization. For example, a company ensures its customers that its bottled water is far better and safer than tap water, and sells it with a considerable markup as a result, but in reality, they merely bottle up that very same tap water. Strictly speaking, the organization develops "successfully," peddling its product to more and more gullible fools, but honest information about will immediately ruin the "success" of both the company itself and its employees, who consciously decided to act dishonestly.

In reality, this is an extremely bad situation, even without taking into account the lack of honesty. Usually, such a state means that the company can collapse at any moment, and even if this doesn’t happen, dishonesty constantly eats away at its "fortune." This happens because employees don’t believe in their dirty-dealing bosses, making the fair assumption that they can’t be trusted with anything. This means that they have an easier time fleecing their managers since they don’t see this as anything to be ashamed of.

That’s why you shouldn’t be afraid of honesty ruining something, but instead that a total lack of honesty will eventually ruin everything. In the same way, if you feel that your position and status are based on dishonesty, this is a very dangerous state. What’s scary is not this state in and of itself, but the fact that such blundering constantly eats away at your resources and energy, only giving you some illusory fluff in return. As a result, in a decade or two, you’ll be left with nothing but deep disappointment at what you’ve spent your life on…

A person with integrity always has an identity, rather than a mere mask, uniform or role. The integration of this particular element of teal management has the greatest difficulties connected to it since integrity is the hardest thing to teach through heart-to-heart conversations with HR. Integrity presumes that we stop seeing faceless "human resources" in our employees, and begin seeing them (and ourselves as well) as real, live people, with all their attendant qualities — even if those qualities aren’t necessary for work. We know for sure that dress code, strict schedule and top-down plans interfere with integrity, and as a result, they cannot exist under teal management. On the other hand, easy transitions between divisions, internships in other departments and companies, and even training in things that are not strictly necessary for the fulfillment of a person’s present duties are all welcome, since such practices help increase employee integrity.

A person with integrity has to like their work. They have to share the company’s evolutionary goal. For this exact reason, it is extremely important for this goal to be a good one: that way, it will be easier for your employees to work towards achieving it, rather than simply doing what they are supposed to.

Task 4

Try to understand the situations in which you lose your integrity. Remember what the reason was and how that influenced the results of your work. Analyze who you are at home and who you are at work. What’s the difference? What do you see as the ideal image of yourself in both of those places? If it’s different, why?

This is extremely necessary to clarify for another reason: for the future, you should know what is keeping your employees from having integrity and focus on eliminating all of these reasons. There will probably be no small number of them, and for that matter, their reason can often be found in your own activities.

There’s one more important nuance: integrity shouldn’t be confused with rudeness. Quite the opposite: a person who couldn’t care less about those around them will do anything that they want, frequently trying in such a way to direct attention to themselves or assert themselves at others’ expense. In other words, they have some deep pain or wound inside themselves that forces them to act that way, which means that they are utterly lacking integrity. Another extreme is also possible: when a person is afraid of pushing somebody out of their integrity, they begin to fool or break themselves, not allowing the emotions that they are feeling to show through. This also points towards their own lack of integrity. This often leads such a person to well up with such a quantity of negative energy, getting more and more annoyed, until they finally explode, subjecting everyone and everything around them to their lack of integrity from which they will spend a great deal of time recovering. Realizing this, this person begins beating themselves up for not holding back, and others now have no idea what to expect from them. As a result, a vicious circle is formed, and the delicate balance among your employees is ruined.

What can you do in such a situation to keep from falling into either of the extremes? It’s very simple to avoid this: all you need to do is note the moments when you personally lack integrity, always analyzing:

1. What was the reason? Or what internal or external event served as a "trigger?”

2. What decision did you make, or what did you say or do in such a state?

By following both of these rules, you will probably see that the state of non-integrity has no advantages. You will also note that surprisingly, identical situations produce identical results over and over again. As a result, the next time that something similar happens, you already won’t have to break yourself or others down: your integrity-losing "program" will simply throw an error.

We will talk in more detail about this in the third chapter (see "Working with your Integrity").

Autonomy

Autonomy is the most common of the three concepts that make up teal management. That’s why practitioners most frequently begin with it in their use of teal instruments. Well, in theory, autonomy is a scale that you can move around on for a very long time. And here’s it’s very important not to rest on your laurels, having decided that everything you’re doing is working fine. For example, I know one manager who considers a situation where "we discussed and I decided" as indicative of his employees’ autonomy, and is sincerely surprised when his subordinates call him an authoritarian: what do they mean?! After all, he figured out what they thought, and then made the only correct decision — simply because he’s the most competent of them all. But it doesn’t even come to mind to question who determines whose competency in such a miraculous hierarchy of ability. Real autonomy is when employees are empowered to make decisions themselves without confirming them with anyone else. Among other things, they have the right not to provide a service to an internal client if there is any reason that they cannot or do not want to do so. Yes, they take responsibility for this in the sense that these internal clients may well disappear, but we cannot speak of any punishments or penalties here: they are strictly forbidden under teal management. Autonomy is the ability to independently make and realize a decision without regard to anyone else.

Autonomy — the ability to independently make and realize a decision without regard to anyone else.

Autonomy is an excellent solution to problems of hierarchy, organizing your employees’ work process such that they take on all of their tasks themselves. Ideally, they will take on all four steps of management, completely independently:

1. Making decisions

2. Planning work

3. Realizing their goals

4. Controlling results

Leadership comes out of specific situations: in different situations, different employees can be the leaders depending on who is best able to do so.

In reality, full autonomy is more like a global ideal of teal management rather than an everyday reality. On a local level, people usually talk about slightly higher levels of autonomy among their employees. Giving them the right to make decisions on any questions that arise in their work has to be done very progressively, all dependent upon how well they have learned the previous steps. The most important part of this process is not to stop, and if you ever take a step back, it should only be done in order to take two steps forward in the future. Your workload can serve as a criterion of progress, which will instantly and clearly show how many and which specific tasks have yet to be turned over.

In this new situation, some managers don’t like that they used to simply say what to do and knew that it would be done, whereas now, they have to spend a lot of time and energy selling their ideas to their subordinates with no guarantee of success. They think that direct management saved them a lot of time and energy. However, if you consider your results not in terms of suppliers who performed as instructed, but in terms of the outcome of well-solved and correctly chosen tasks, then suddenly it turns out that the speed of carrying out orders is far lower than the work on the solution that a subordinate came up with themselves. Such employees don’t have to be "pushed" constantly in order to get to the next step of the project. For that matter, if you look at how much time and energy is spent overall on making decisions and their fulfillment, then direct management is far less effective.

Combining all three whales of teal management

For me, the most vivid example of a true teal approach in practice is the Dutch medical service Buurtzorg (which translates as "neighborhood care"), where all three criteria set forth by Frederic Laloux in "Reinventing Organizations" are fulfilled. Its evolutionary goal is as follows: "So that patients who need visiting nurse care need it as little as possible." For that matter, as you can guess from the name, that is exactly what the company does! In other words, according to such an evolutionary goal, employees of such a company should take such actions that result in their clients turning to them less and less frequently! Buurtzorg employees work to these ends, and with great success: their customers need help an average of two times less frequently than they do with their competitors. It’s not because they are special in some way; simply put, "Neighborhood Care" works with its charges such that the need for visiting care is reduced.

One of the reasons for this is the deep integrity of the nurses who work there. The formalities of their job were simplified as much as possible, without any plans for required work levels; turning away from strict schedules; and removing restrictions on the length of visits to patients. They also relieved their employees of the requirement to spend a lot of time filling out reports and paperwork for the office. In this system, the medical professionals don’t work for the office; instead, the office works for them, helping them serve their patients better and more efficiently by optimizing their time and expenses. In total, just 50 office employees successfully support a staff of nurses and therapists that currently numbers about 14,000! The presence of total autonomy within both office departments and the teams on the ground allow the organization to continue growing fast, opening branches around the world — even in Russia!

Rights and responsibilities

The teal system of management is also distinguished by the fact that rights and responsibility are always held by a single person. This is an extremely important principle whose consistent application will automatically solve many of your organization’s already established problems. Generally speaking, any problem is always located somewhere between rights and responsibility, and the further the two are separated, the more entrenched it becomes. Meanwhile, its solution miraculously appears as soon as rights and responsibility are joined together in a single pair of hands. Why is that that the problem caused nothing but unpleasantness until that point, and nobody was able to handle it? The problem is that a person who bears responsibility for the issue but doesn’t have the rights necessary to work with it can’t solve the problem, no matter how much they want to. They suffer, torture themselves, and slowly lose all motivation as a result, but is in no state to do anything. Meanwhile, the person with rights but no responsibility will always find something to do, and they will ultimately just not get around to this problem. Ideally, this person should pass on their decision-making rights to the person who bears the responsibility, and if they don’t want to or cannot do so, then they must take on the responsibility for the problem themselves.

In actuality, this responsibility will catch up to them sooner or later. It only seems as though they can pin it on others ad infinitum, making active use of those rights that they need to fulfill their own tasks. The laws of the universe, however, will hold them to account — and this will be the sum total of the responsibility that they should have taken on while pinning it on others instead. What’s worse, I’ve encountered situations where the upper echelons of leadership have put up aggressive defenses, distanced themselves from their employees’ problems while turning subordinates at all different levels into sacrificial lambs — or even firing people for things that they couldn’t possibly fix since the very same top brass failed to give them the rights they needed to fix them. Ultimately, the whole enterprise falls to its knees and either closes entirely, leaving everyone without a job, or a new owner appears and breaks up this whole motley crew.

Therefore, boldly study any problem you face in this particular way, through the lens of rights and responsibility in order to immediately ascertain what needs to be done in order to solve the situation. Of course, besides simply understanding this, you will need a certain amount of political will as well. In a teal system of management, rights and responsibility must always be together, while any consistent problem is an indicator that this is not the case. That’s why it would make sense to start working preventatively. One of the best ways to make sure that rights and responsibility always go hand-in-hand is to use promises rather than assignments.

Assignments and promises

An assignment is a requirement whose performance is imposed upon another, while responsibility remains with the person who assigns it.

A promise is a requirement that one takes upon themselves, and since the person who makes the promises takes on the responsibility for its fulfillment, they need to receive the rights necessary to do so.

Task 5

Try to define the difference between an assignment and a promise.

In both cases, it is an obligation:

— But an assignment is an imposition on someone;

— While you take a promise upon yourself.

For that matter, the essence of the distinction is not merely in the name, so you can’t merely rename your assignments as promises. It would be very easy, after all, to call a subordinate into your office and entrust the fulfillment of certain "promises" to them. But you’ll feel the difference immediately: it is based on the transfer of responsibility. With an assignment, it remains with the person who gives the assignment, no matter how you decide to call the assignment. This is the person who lost sight of the fact that the person carrying out the assignment lacks some sort of information or skills, has a poor relationship with the people with whom they need to work, or is busy with other work.

In the case of a promise, the person who makes it takes all of that responsibility on themselves!

Task 6

Think about what you need to have in order to promise something to somebody.

It’s obvious that you need to understand that you can fulfill your promise, which means that you have all the necessary authority and resources to truly influence the situation. In other words, a real promise becomes an excellent tool that allows companies to provide all the necessary rights to the worker that should bear responsibility for something. There’s even a special phrase for this. Ask your employee, “What exactly do you need in order to make this promise?”

There’s one more important trait of a promise: it must only contain the result that the client needs, and it cannot capture the process. You shouldn’t say, "I will carefully wash the floors from 10 am to 6 pm"; the correct answer would be, "The floor is always clean during this time interval." This is of cardinal importance so that the employee can finally start doing what the client needs. It’s even more important to help them stop doing what they don’t need to — for example, making a show of feverishly working with a bucket and cloth.

Aside from all of these advantages, promises have a surprising way of becoming the exact kind of communication protocol that will help eliminate enmity between employees and divisions within the company. If you look at the way these conflicts develop, it becomes clear that they are self-replicating: remember the vicious cycle that I described above. It is easy to break by starting a process of communication between the warring parties. But mere communication will only serve to increase the level of loathing they feel for each other, as they will each begin to remember all of the other party’s transgressions and they will part ways with even greater certainty in their opinions: look at the awful people we have to work with! That’s why it’s necessary for the meeting to be conducted by some independent third person, or maybe even an invited outside party, who will begin setting this protocol for communication and make sure that both participants follow it.

This meeting leader begins by offering each party the chance to talk about the difficulties they are experiencing, without any relation to anyone else’s actions. In other words, instead of accusing their colleagues of constantly making corrections to the project, an employee should instead say that it’s very unpleasant to constantly redo the same work over and over again. This is absolutely necessary, since negative emotions will prevent everyone from continuing to communicate effectively, and therefore it’s best to "let them out" in a way that doesn’t build up negativity towards the other party but softened the blow of the situation instead. Besides, it’s not as pleasant to admit to your own problems as it is to blame somebody else for them, so the process will simultaneously "extinguish" the wounded soul, rather than fanning the flames.

Then they go on to discuss who makes what kind of promise to whom in order to keep such a situation from reoccurring in the future. This can include a discussion of any parameters of the result to be delivered by the supplier to the client, but they should never discuss who should specifically do what. This is of the utmost importance in order to completely remove the emotional component of this conversation and to keep the whole conversation constructive, logical and specific. An attachment to the future allows you to distance yourself from the problems of the past and present, while a positive approach of asking "how can we keep there from being problems in the future?" reorients the warring factions towards the kind of collaboration that was previously sorely lacking.

The meeting leader also has to make sure that all of the promises meet certain formal criteria.

1. A client can only ask a supplier for a promise in order to fulfill one of their own, aside from the so-called core promises that companies give their clients.

2. A promise is always a result that can be separated from the supplier.

3. Identical promises cannot fulfill different roles. If there are two consecutive or successive promises, one of them has to be given directly; if there are two parallel promises, then you have to understand who is responsible for what, and each supplier can only promise their part.

4. You can’t create “loops”: I promise you something in order for you to fulfill the promise that you’ve made to me so that I can fulfill my responsibilities to you. In these situations, you should use conditional promises. For example, instead of creating a counter-promise, such as “Our division will only submit correctly completed invoices to accounting so that they can fulfill their promise to us to pay them,” we would create a single promise: “All correctly completed invoices submitted to accounting will be paid within one business day.”

5. A supplier should receive all the rights they need for a given promise.

The fourth bullet point demands additional explanation. If employees can’t make promises to each other, that means that in any partnership, one of them will only be a client and the other will only be a supplier. Somebody might see discrimination in that. I would respond immediately that teal management is by no means about equality for all, but about prioritizing what’s actually important. Others might see the potential for serious conflict between the divisions that we want to reconcile. I’ll jump in to dispel their concerns: there’s a clear logic to who becomes the client and who becomes the supplier. It’s protected in the first bullet point of the list above. But here’s a question: if a client can only ask for a promise from their supplier in order to fulfill a promise of their own, then where do the initial promises come from in the first place? From the company’s promises to their clients. These are what we call the "core promises," and all other promises within the company only appear in order to fulfill them.

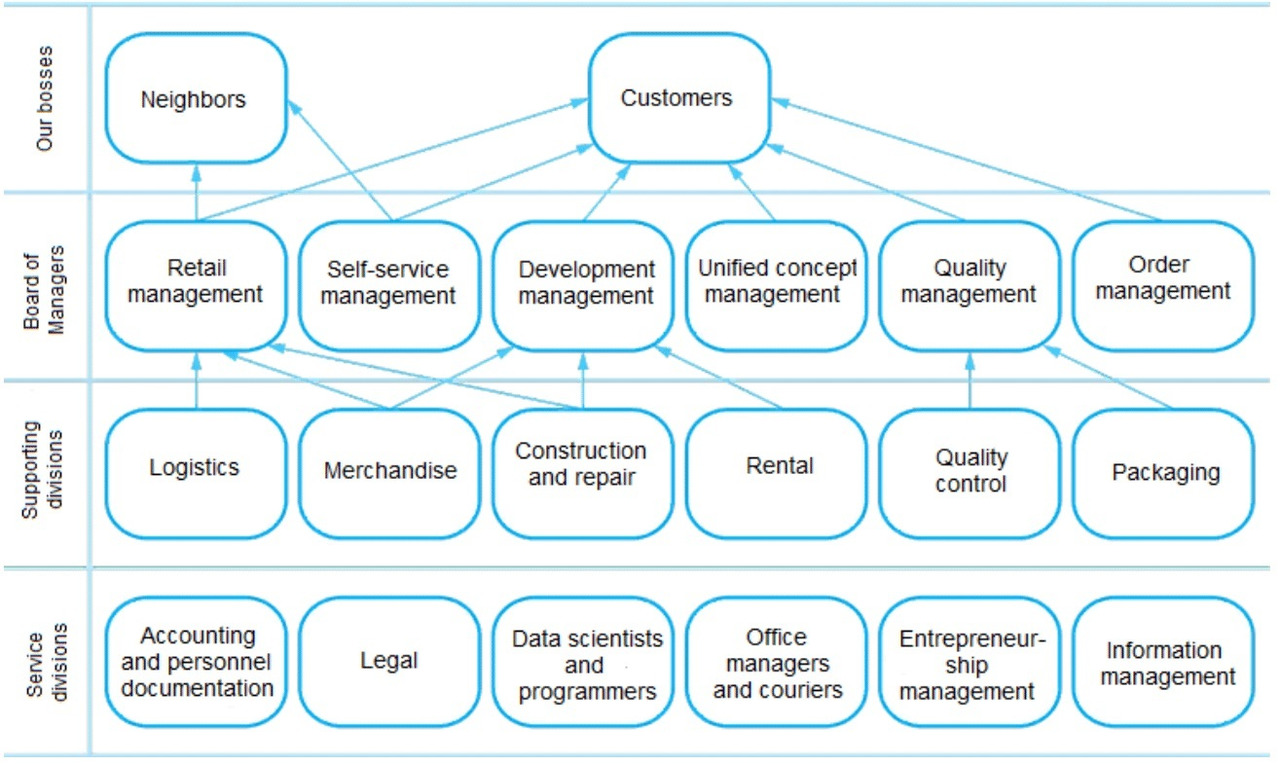

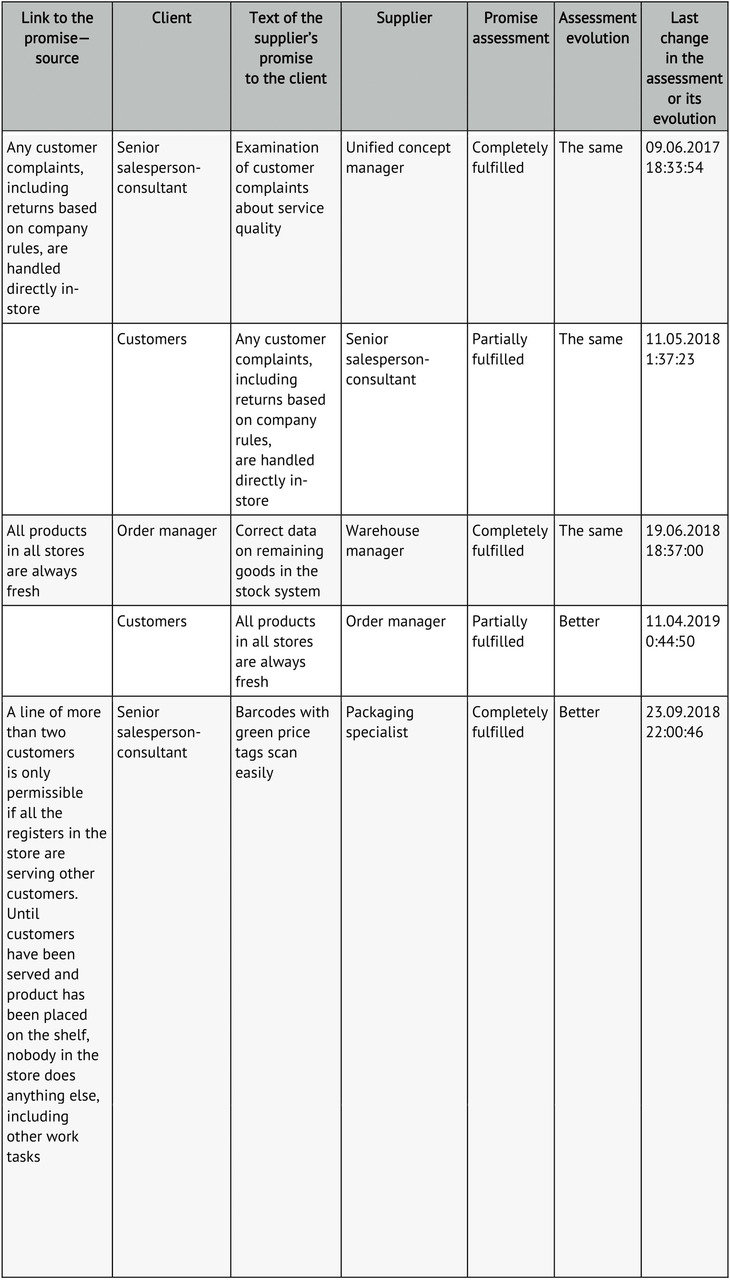

This is a diagram of the key promises we make to VkusVill. The promise arrows coming from the service departments are not drawn, as they go to all other structures and divisions within the company.

Special terminology

You probably have a couple of questions: who are these "neighbors" bossing us around alongside our customers? And what is this mysterious "self-service," with a whole division dedicated to it?

I’ll go in order: at VkusVill, the notion of "neighbors" is an established term that we use to talk about people who live near our stores. These people might not be our customers at all, but that doesn’t relieve us of any responsibility; therefore, we promise them that our stores won’t ruin their quality of life. For example, if our store’s exhaust fan is located under their window, then we will install sound deadening, or even pay for him to install double-glazed windows. As you can see in the table, our retail and self-service (I’ll explain what this word means in a bit) divisions make these promises to our neighbors: they’re the ones who think through all of these nuances since they’re the ones who work with the operation of each store location. There were even cases when employees of the aforementioned divisions had to spend nights with these very same "neighbors" to ascertain just how serious the noise from our store was during the hours when they insisted that the street would grow quiet and the noise became noticeable.

"Self-service" refers to stores that consist of a simple refrigerator, shelf and register: people walk up, take what they need, and ring themselves out. We don’t have any employees nearby at all — they only come by in the morning to stock the shelves with fresh products and then leave. Everything else is based on trust. Today, there are more than two hundred of these self-service locations in offices of various Moscow companies.

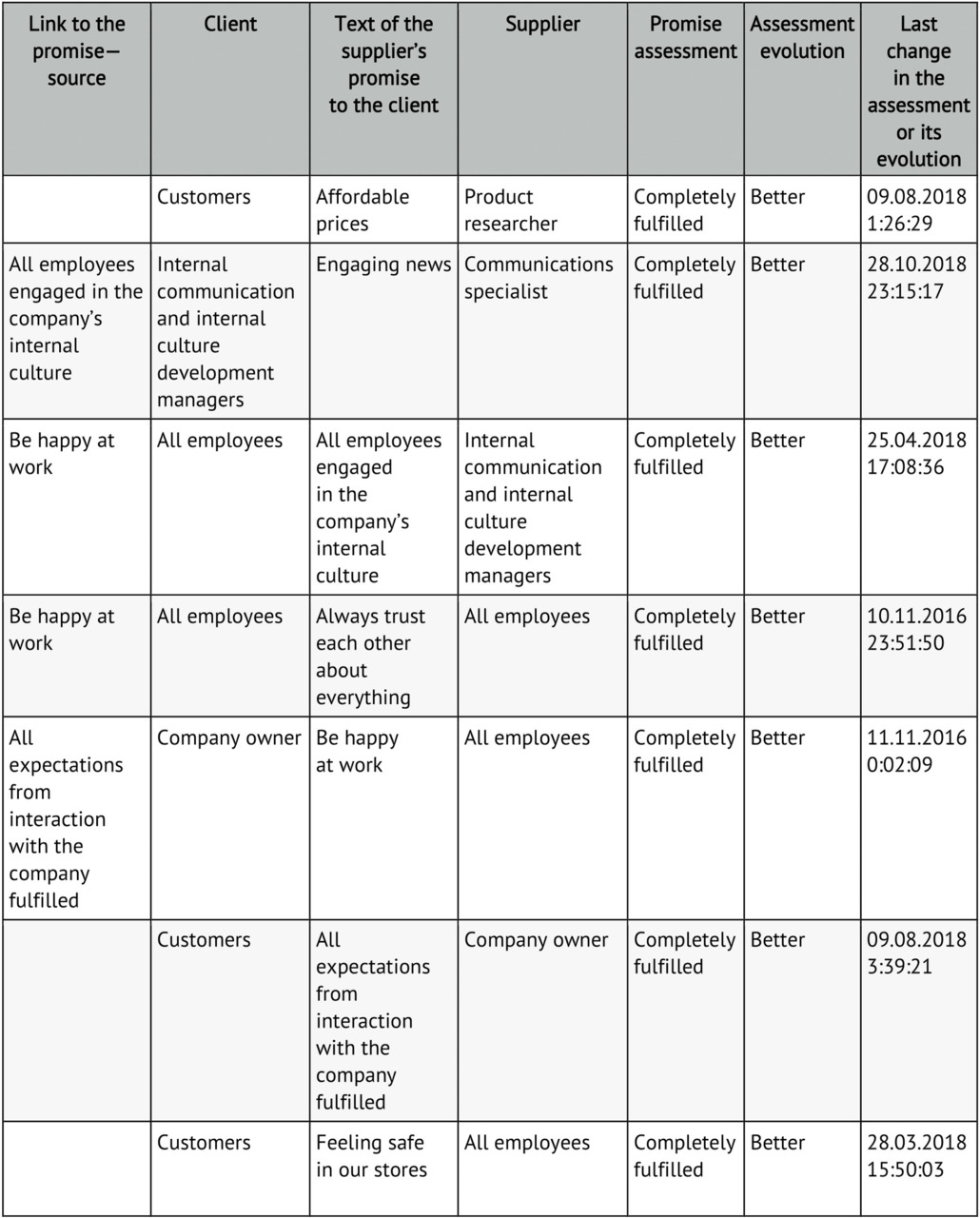

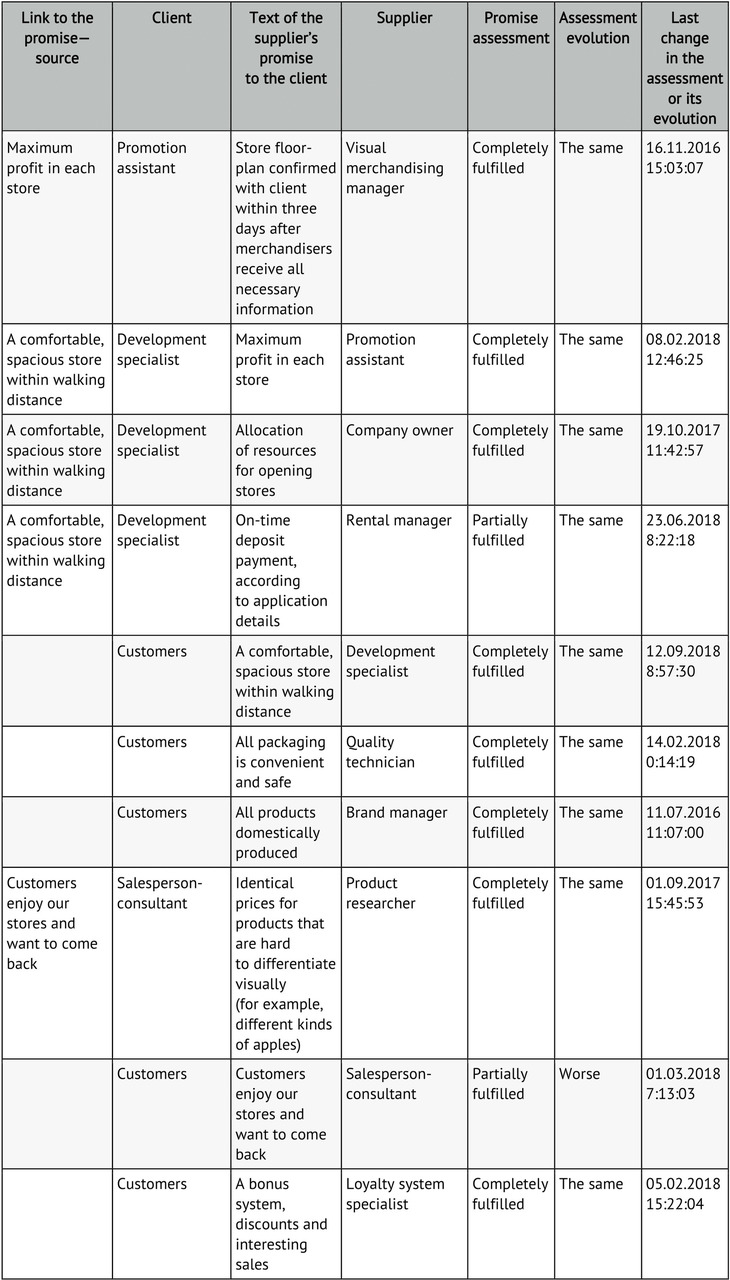

Okay, the promises have been made. Now all that’s left is to create a unified summary table in our accounting system to store them.

This is roughly how such a table should look.

Бесплатный фрагмент закончился.

Купите книгу, чтобы продолжить чтение.